After my grandfather, 1LT Andrew Carrico of Company D, passed away in October of 2016, my beloved grandmother Jane gave me some of his books on military history and leadership. They are a special part of my collection, but the funny thing is....Grandpa really disliked some of them. He was painfully aware of just how few of the tens of thousands of books published on World War II even mention the 11th Airborne Division, let alone his proud 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment (you can likely count them on two hands)

After my grandfather, 1LT Andrew Carrico of Company D, passed away in October of 2016, my beloved grandmother Jane gave me some of his books on military history and leadership. They are a special part of my collection, but the funny thing is....Grandpa really disliked some of them. He was painfully aware of just how few of the tens of thousands of books published on World War II even mention the 11th Airborne Division, let alone his proud 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment (you can likely count them on two hands)

When Grandma shared Grandpa's books with me, she pointed to one with a smile and said, "Andy hated that one. It doesn't even mention the 11th." And as a historian for the 511th PIR, and the 11th Airborne as a whole, I have to agree with Andy. While researching, writing and publishing WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY IN WORLD WAR II, I found myself disappointed by the lack of media coverage regarding the Angels' history (I admit to some bias there).

One of the most important aspects of the Angels' history that is hardly mentioned anywhere is their incredible landings at Atsugi, Japan between August 28-30, 1945. Apart from further cementing the reality of the war's end, this made the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment the first fully-formed foreign regiment to land on Japan in the country's long history, not to mention the first Allied unit into Japan at the war's end.

"We're Going to Japan"

When Japan announced their intention to surrender on August 14, 1945, Major General Joseph May Swing's 11th Airborne Division sat, bored, on Okinawa near the National Cemetery, asking themselves if the surrender was all just a ruse to lure them onto the mainland only to destroy the first Americans to land. And since they were an airborne division, the Angels felt that they would indeed be some of those first "sacrificial lambs" sent in to secure some crucial target(s) or another.

When Japan announced their intention to surrender on August 14, 1945, Major General Joseph May Swing's 11th Airborne Division sat, bored, on Okinawa near the National Cemetery, asking themselves if the surrender was all just a ruse to lure them onto the mainland only to destroy the first Americans to land. And since they were an airborne division, the Angels felt that they would indeed be some of those first "sacrificial lambs" sent in to secure some crucial target(s) or another.

Before the surrender was announced, however, the waiting Angels were somewhat “hellbent for election” according to one trooper. Even so, General Swing's men questioned if they would make it through the potential invasion on Japan, should the operation be called for. Leyte and Luzon had both bled the 511th PIR sorely and the paratroopers who had managed to survive both campaigns quietly wondered if the "third time was the unlucky charm."

But that didn't stop General "Jumpin' Joe" Swing from walking into the hospital treating many of his Luzon wounded and booming, “I want every man that can walk…out of here today. We’re leaving the island; we’re going to Japan.”

General Swing's battle-worn Angels were ready for the war's end and while all were ready to do their duty if called upon to jump on mainland Japan, no one shed any tears when news of the atomic bombs' destruction at Hiroshima and Nagasaki spread through the Division's Okinawa camps. But there wasn't any wild celebrating either; the Angels had fought Imperial Japan too long to believe that the enemy was ready to throw in the towel just yet.

In truth, many were and another firebombing raid on Tokyo on August 14 sealed the decision. Before the last aircraft returned, Japan surrendered and President Harry S. Truman declared to reporters at the White House, “This is the day we have been waiting for since Pearl Harbor. This is the day when Fascism finally dies, as we always knew it would.”

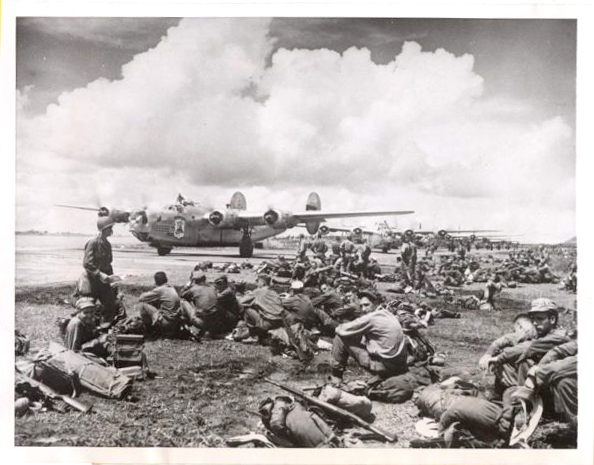

“Victory in Japan Day”, or “VJ-Day”, celebrations erupted around the world from London to Luzon, Pearl Harbor to Paris, and New York to New Guinea. But on Okinawa, the Angels took several test jumps from modified B-24 bombers since a C-46’s fuel tanks could not make it to Tokyo and back with an acceptable margin of safety. The B-24s were quickly rejected as they lacked sizeable jump doors and could not slow down enough for safe jumping. In the end, Douglas C-54 Skymasters were selected as the Angels’ main source of conveyance and since most of the C-54s were commercial, the 511th’s paratroopers were beyond pleased to see ten rows of comfortable seats.

Perhaps more eyebrow-raising, though, were briefings where the paratroopers learned they would depart from Okinawa's Kadena Airstrip combat-loaded, or “armed to the teeth” as one trooper noted. While Japan proclaimed surrender, there was still concern that the whole affair was a trap that would spring shut once the Allies had a large force on the ground. The Angels were told that if this occurred, they would have to quickly exit their aircraft and stand their ground until additional forces could link up from the air or overland after amphibious forces pushed in from the coast. It was not a pleasant scenario to imagine but had to be considered.

A few days later, August 24, the Angels received Field Order No. 34 outlining their final instructions upon landing in Yokohama, including the need to remove all Japanese within a three-mile radius of the airfield and to guard General Douglas MacArthur and his entourage.

It was official: General Swing’s Angels would do what Kublai Khan’s fleet could not do in 1274 and 1281. The 11th Airborne would be the first full military unit in history to occupy Honshu.

A Historic Airlift to Japan

After a few days’ delay due to Typhoon Louise, on August 30 (Z-Day) the combat-loaded 511th PIR’s vanguard boarded their craft and led the 11th Airborne past Mt. Fujiyama and Kamarkura’s great bronze Buddha on their way to the bomb-damaged Atsugi Airfield 15 miles outside Yokohama. With B-29s and P-51s flying escort, the 11th Airborne’s second historic airlift ran eleven hours a day and landed one C-54 every three minutes. So many craft were flown in that at their departure point, Okinawa's Naha airstrips, C-54s were parked as far as two miles away on dirt roads.

And while the 11th Airborne’s “rivals” in the 1st Calvary Division claim the slogan, “First in Manila, First in Tokyo”, General Joseph Swing’s boys have known for decades that they were the first in Japan as their pathfinders/recon platoon had landed on August 28 alongside Colonel Charles Trench of MacArthur’s HQ. Additionally, several Angels "wandered" into Tokyo over the next few days to explore the city.

As the 511th’s main body roared at treetop level over the Kanto Plain (where they and Eighth Army had been scheduled to fight during the invasion), the paratroopers’ trained eyes noticed the anti-aircraft emplacements that could easily blow them out of the sky.

Fortunately, the Angels landed at Atsugi without incident with General Swing and his staff in the first plane. Colonel John Lackey piloted the craft with Swing sitting behind him accompanied by G-3 LTC Douglas Quandt, G-2 Lieutenant Colonel Henry J. “Butch” Muller, and twenty-seven-year-old Colonel John “Jack” Atwood the Division’s Signal Officer. Prior to departure, Atwood had traveled to Manila where General MacArthur’s own Chief Signal Officer questioned Jack’s youthful age before telling him that the Angels would oversee communications for 8th Army HQ in Yokohama as well as MacArthur’s staff. As such, members of the 511th Airborne Signal Company rode in the Angels’ second plane and quickly established communications with Allied command once they landed.

Also traveling in the flight (Baker 60), the 511th’s Colonel Edward "Big Ed" H. Lahti selected war correspondent Don Munson of Palm Beach, Florida, to go with him. In truth Don was more or less “attached” to the 511th’s HQ, but his was a coveted honor as a longing to be “the first in Japan” infected soldiers and reporters across the Pacific. Every Angel was proud that CINCAFPAC (Macarthur) had designated the 11th Airborne to lay claim to that historic achievement and since the division was making headlines around the world, Munson was looking forward to writing more of them.

Not having much to do on the ground at Atsugi, however, Don and correspondent Private First Class Frank G. Kiddoo, Jr. “acquired” a ride into Tokyo on Z-Day, five days before General Douglas MacArthur entered the city and nine days before 1st Calvary did. As the capital had been declared off-limits, the two journalists wisely kept their Tokyo “tour” quiet until after the notoriously jealous general declared his own triumphal entry.

Cake-Slicers

When a well-tanned Gen. Swing dropped his six-foot frame onto the Atsugi tarmac at 0600 on August 30 (Z-Day), he was the highest-ranking Allied officer in Japan. He was greeted by a delegation of Imperial admirals and generals dressed in black, including head of the Imperial Army’s intelligence department Lieutenant General Seizo Arisue (Swing is center with 11 A/B helmet in the photo to the right). With much bowing and scraping, the Japanese extended hands of welcome towards the first enemy officer to stand on their soil in six hundred years. Adhering to his military purpose, General Swing ignored the offered hands and told the Japanese that he expected all officers to remove their Samurai swords and pistols (which only held one bullet for themselves should the “blood-thirsty” paratroopers attack). Taken aback, an interpreter explained that the swords were merely symbols of authority, not weapons. Swing, who had seen such swords used to attack and mutilate his men and civilians alike on Leyte and Luzon, rose up to his full height. Towering more than a foot over the Japanese, the Old Man boomed, “From now on I’m the ‘authority!’ So, get those cake-slicers or whatever-they-are in a pile on the ground without any more delay.”

When a well-tanned Gen. Swing dropped his six-foot frame onto the Atsugi tarmac at 0600 on August 30 (Z-Day), he was the highest-ranking Allied officer in Japan. He was greeted by a delegation of Imperial admirals and generals dressed in black, including head of the Imperial Army’s intelligence department Lieutenant General Seizo Arisue (Swing is center with 11 A/B helmet in the photo to the right). With much bowing and scraping, the Japanese extended hands of welcome towards the first enemy officer to stand on their soil in six hundred years. Adhering to his military purpose, General Swing ignored the offered hands and told the Japanese that he expected all officers to remove their Samurai swords and pistols (which only held one bullet for themselves should the “blood-thirsty” paratroopers attack). Taken aback, an interpreter explained that the swords were merely symbols of authority, not weapons. Swing, who had seen such swords used to attack and mutilate his men and civilians alike on Leyte and Luzon, rose up to his full height. Towering more than a foot over the Japanese, the Old Man boomed, “From now on I’m the ‘authority!’ So, get those cake-slicers or whatever-they-are in a pile on the ground without any more delay.”

The Rising Sun had set at 0605 and the chastened Japanese quickly covered the tarmac with several rows of razor-sharp blades, some of which had been in their families for hundreds of years. Following the war many Angels who had been sent home to recover from wounds received swords as souvenirs from General Swing and the gifted blades may have come from this pile or those surrendered during the ensuing months.

Of their initial landing, Captain Stephen Cavanaugh, the 511th PIR's 1st Battalion Executive Officer, noted, “The Japanese commander of the field assured us that the field had been secured by his forces against any attacks by a few fanatical Japanese Army units that refused to obey the Emperor’s orders to surrender. Not taking his word, we proceeded to establish our own security and covered the arrival of Division elements as they landed.”

The paratroopers had good reason to be concerned. They were now outnumbered tens of thousands to one and while Japanese leadership confirmed their intentions to surrender, everyone remembered how that same leadership had snowed Washington leading up to Pearl Harbor. As General MacArthur later noted, “One false move and the Alamo would look like a Sunday-school picnic.”

First Flag Raised Over Japan

After General Swing’s staff set up the first Allied CP in Japan at 0730 in a hangar, William “Bill” F. Rudolph of the 511th Airborne Signals Company was ordered to guard the ultra-secret SIGABA code machine as Swing established contact with MacArthur’s HQ in Manila. Ten minutes later a photographer for Life told Rudolph to help raise the American flag, perhaps hoping to capture a Joe Rosenthal-esque photo. Standing by his orders to guard the SIGABA machine, Rudolph declined. Instead, the first American flag on Japan’s homeland was raised atop the building by the Angel’s Lieutenant Thomas S. Smith and Privates First Class Arthur Labash, Donald J. Mack and Frank Huber (see photo to the right - left to right unknown).

After General Swing’s staff set up the first Allied CP in Japan at 0730 in a hangar, William “Bill” F. Rudolph of the 511th Airborne Signals Company was ordered to guard the ultra-secret SIGABA code machine as Swing established contact with MacArthur’s HQ in Manila. Ten minutes later a photographer for Life told Rudolph to help raise the American flag, perhaps hoping to capture a Joe Rosenthal-esque photo. Standing by his orders to guard the SIGABA machine, Rudolph declined. Instead, the first American flag on Japan’s homeland was raised atop the building by the Angel’s Lieutenant Thomas S. Smith and Privates First Class Arthur Labash, Donald J. Mack and Frank Huber (see photo to the right - left to right unknown).

From their elevated position, the delighted trio then watched General Robert Eichelberger’s C-54 touch down. Eichelberger had a lot to do and not a lot of time to do it in. After asking General MacArthur to give him two days to assess the conditions in Yokohama before he arrived, MacArthur replied that he and General Swing would have two hours.

Curraheed

While Swing and Eichelberger conversed on the tarmac, the 11th Airborne’s G-3 Lieutenant Colonel Henry “Hank” Burgess rode with a group of Japanese officers thirteen miles to a building to discuss what would happen when MacArthur arrived (wanting the Japanese to lose face, General Swing refused to go). Following the meeting, Burgess stood to leave when one of the Japanese generals grabbed Hank who noted, “Up to that point, no Japanese had ever touched me, although several had tried.”

Knowing that he was the only American for thirteen miles, the battle-hardened trooper’s reflexes kicked in. Burgess slapped the general’s hand away with his knife then flipped the former enemy around with his left arm around his neck and pressed the tip of his knife against the man’s throat.

Everyone froze. The room was deathly quiet when another Japanese officer softly informed Burgess that it was military courtesy that the ranking officer leaves the room first. The Silver Star recipient calmly replied, “I am very familiar with military courtesy, and at this time one American major outranks five Jap generals.” Burgess then left the room…first.

Back at Atsugi, the transports for the 187th Glider Infantry Regiment and 511th and 188th Parachute Infantry Regiments were landing in three-minute intervals and Colonel Ed Lahti immediately set out to tour the devastated city with Yokohama’s Chief of Police to select housing for his paratroopers. During their excursion, Lahti and his staff were amazed to see spider holes in backyards where families would have fought to the death had the Allies invaded. His battle-trained eye could see defensive points that his paratroopers would have had to fight through and was a chilled as he pondered the scenario.

After seeing to the billeting of his three battalions, Colonel Lahti’s HQ Company set up shop under the grandstand of a nearby baseball field which required slit trenches that quickly became the bane of the CP’s troopers. Given Lahti’s love of baseball, his affinity for the sport probably affected his judgement as the location proved quite intolerable. Even so, the Angels elected to honor baseball great Lou Gehrig by naming the field after him.

“Big Ed’s” orders were to occupy Yokohama and secure the docks and landing areas around Tokyo Bay for the arrival of additional troops as well as the Peace Delegation, a mission the 511th accomplished by August 31 (Z+1). As Allied officials and units began arriving over the next three days, the Angels’ band under Warrant Officer Robert M. Bergland met them on the Osanbashi pier and played various marches, anthems or unit favorites in welcome.

One of those early arriving groups, which rode to the pier directly from the Atsugi airfield, came from all over the 11th Airborne itself to help form Gen. MacArthur’s Honor Guard.

General MacArthur's Honor Guard

Almost two months earlier, while the 511th PIR was still outside Lipa on Luzon, MacArthur asked Gen. Swing to form part of his Honor Guard for Japan from the 11th Airborne. Swing passed word to his regimental commanders and Col. Lahti ordered his company commanders to select their best paratroopers for the duty, with the stipulation that each trooper must be over 5’11”.

Almost two months earlier, while the 511th PIR was still outside Lipa on Luzon, MacArthur asked Gen. Swing to form part of his Honor Guard for Japan from the 11th Airborne. Swing passed word to his regimental commanders and Col. Lahti ordered his company commanders to select their best paratroopers for the duty, with the stipulation that each trooper must be over 5’11”.

The 511th PIR supplied one platoon of five squads led by two officers with sixty-six enlisted men that would guard MacArthur during the surrender signings, at his Yokohama HQ the five-story New Grand Hotel (see photo to the right), and his home at the U.S. Embassy. And while it sounded like a ceremonial position, there were still fanatical Japanese soldiers and civilians who wanted nothing more than to see their enemy’s Supreme Commander dead, or the surrender ceremony disrupted. As such, the Honor Guard took their responsibilities seriously.

Colonel Lahti’s 68 handpicked paratroopers had been awarded a combined total of over 400 medals, badges and ribbons and would be led by my grandfather’s friend, one of the original “New Guinea Wolves” 1st Lieutenant Ralph Ermatinger of Fox Company and the battlefield-commissioned 2nd Lieutenant James C. Watkins of George Company. The officers were assisted by Platoon Sergeant and Distinguished Service Cross-recipient Sergeant Edward L. Reed of Charlie Company with Privates First Class Harry A. Swan and Robert Wilms acting as runners.

Another well-deserved addition to the Honor Guard was Private First Class Alex “Chief” Village Center who won the foot race at Camp Polk and later declared that the men of D Company were his “brothers now” after his own siblings died. D Company’s Chauncey Poole later noted that Alex was always giving destitute Japanese children candy from his rations as well as cigarettes to adults in Hokkaido.

Also selected from D Company were Staff Sergeant Wilcox, Wilbur, now recovered from wounds received on Luzon, Private First Class John Tkacyk who pulled my Grandpa out of harm’s way during a Luzon firefight, and Private First Class Clyde Johnson. In truth, most in the Honor Guard were lucky to be alive. Not only had they survived the odds of combat, on August 11, while the 511th was rushing to depart for Okinawa, some of Lieutenant Ermatinger’s special platoon had boarded a B-24 marked with unlucky 13 but were told to move forward to plane number 12. It was Plane 13 that crashed, killing eight of their D Company comrades.

The 511th’s platoon joined the complete 11th Airborne Honor Guard under Maj. Tom Mesereau, the All-American tackle from West Point who was 6’3” and tipped the scales at 220-pounds. Gen. Swing wrote, “He should make the brass hats appear rather colorless in comparison.”

The Payoff - General MacArthur's Landing

At 1419, eight hours after Gen. Swing landed, Gen. MacArthur’s converted C-54 Bataan touched down at Atsugi amid great fanfare. Lieutenant Ermatinger and the 511th’s Honor Guard moved to stand under the craft’s wings and watched the corncob pipe-carrying, sunglasses-wearing general greet Swing and the 11th Airborne Band on the tarmac. After the Angels played several numbers, MacArthur said to Warrant Officer Robert Bergland, “I want you to tell the band that that’s about the sweetest music I’ve ever heard.” (see photo to the right - left-to-right: Major General Joseph M. Swing, Warrant Officer Robert Bergland, General Douglas MacArthur)

At 1419, eight hours after Gen. Swing landed, Gen. MacArthur’s converted C-54 Bataan touched down at Atsugi amid great fanfare. Lieutenant Ermatinger and the 511th’s Honor Guard moved to stand under the craft’s wings and watched the corncob pipe-carrying, sunglasses-wearing general greet Swing and the 11th Airborne Band on the tarmac. After the Angels played several numbers, MacArthur said to Warrant Officer Robert Bergland, “I want you to tell the band that that’s about the sweetest music I’ve ever heard.” (see photo to the right - left-to-right: Major General Joseph M. Swing, Warrant Officer Robert Bergland, General Douglas MacArthur)

The ramrod-backed paratroopers watched the helmet-wearing Gen. Swing pose for photos with MacArthur and his staff (see first photo at beginning of this article, Swing is far left in helmet). With a smile, MacArthur turned to Gen. Eichelberger, under whom the Angels fought on Luzon, saying, “Well, Bob, it has been a long, hard road from Melbourne to Tokyo but as they say in the movies, this is the payoff.”

MacArthur’s decision to land at Atsugi was considered quite a risk as it was unknown if Japanese suicide squads would indeed try to kill their great enemy. Winston Churchill even noted, “Of all the amazing deeds in the war, I regard General MacArthur’s personal landing at Atsugi as the bravest of the lot.”

After addressing the gathered troops, reporters and Japanese, MacArthur winked at the Angels’ Honor Guard before stepping into an old Lincoln with Gen. Eichelberger to head to Yokohama’s New Grand Hotel, fifteen miles away. The Honor Guard and 500 paratroopers of the 511th escorted the convoy of Japanese vehicles with a red fire engine in the lead that kept breaking down.

As the Angels and the Brass lumbered down the road, Imperial soldiers along the road about-faced as they approached. Some in the 511th grew angry at the apparent act of derision, one even declaring he would shoot the next Japanese who turned, until it was explained that their actions were a sign of respect, one previously reserved for the emperor himself. The cocky Angel could live with that.

And while historians often report that the Japanese soldiers turned as the first Allied soldiers made their way down the streets, they almost always forget one little detail: Lieutenant Ralph Ermatinger, CO of the 511th’s Honor Guard, noted that a captain he traveled with in the first truck had told their interpreter to order the Japanese soldiers to about face as they advanced. Whether the turns were out of respect as often reported or done as ordered is lost to history.

After their hour-long journey, General MacArthur was given a tour of the New Grand Hotel by its kind owner, Yozo Nomura, “the King of Curios”, while the Angels’ pitched their tents outside amid the surrounding rubble (some also stayed in a house next door). MacArthur was led to room 315 with its wonderful view of Yokohama’s port and 160 general officers from various Allied militaries would fight to find quarters in the hotel which led one 4th Marine RCT officer to quip, “Our first wave was made up entirely of admirals trying to get ashore before MacArthur.”

The 11th Airborne Division's General Joseph M. Swing had already beaten them to it. At 1730 while MacArthur was settling in, Swing moved his CP to the Rising Sun Oil Company compound near the Yokohama racetrack with its fifteen beautiful American-style homes, complete with spacious rooms (MacArthur had considered moving his own HQ there before selecting the New Grand Hotel). Yokohama, for the most part, was a ghost town. Swing’s Angels shook their heads at the clusters of cement-block huts built from the rubble left behind by the Air Corps’ firebombing raids on May 29 which had destroyed 80% of the city. Still-standing shops were boarded up, windows were shuttered and the few civilians on the streets bowed or waved stone-faced as the troopers passed. It was surreal and for two Angels driving trucks to and from the Atsugi airfield, it was about to become even more so.

The Angels and the Imperial Palace

After a handful of trips, Private First Class Edward J. Baumgarten of G Company and his buddy took a wrong turn. They kept going, hoping to find the landing strips before nightfall, and after about an hour, Baumgarten found an English-speaking Japanese who pointed to a large, green area and said, “Imperial Palace, one block.” The two lost, lowly paratroopers were in the heart of downtown Tokyo and Baumgarten remembered, “A couple of weeks later, I saw in the Stars and Stripes a picture of the 1st Calvary going into Tokyo: ‘First GI’s enter Tokyo.’ But I’d been there two weeks ahead of them.’’

After a handful of trips, Private First Class Edward J. Baumgarten of G Company and his buddy took a wrong turn. They kept going, hoping to find the landing strips before nightfall, and after about an hour, Baumgarten found an English-speaking Japanese who pointed to a large, green area and said, “Imperial Palace, one block.” The two lost, lowly paratroopers were in the heart of downtown Tokyo and Baumgarten remembered, “A couple of weeks later, I saw in the Stars and Stripes a picture of the 1st Calvary going into Tokyo: ‘First GI’s enter Tokyo.’ But I’d been there two weeks ahead of them.’’

By sundown on August 30 (Z-Day), General Joseph Swing had 4,200 Angels around Yokohama, a force he felt was sufficient to fight with if Japanese radicals chose to attack them or MacArthur’s CP. By September 7 (Z+8), the 11th Airborne had moved 11,708 men, 640 tons of supplies and over 600 Jeeps and trailers to Atsugi which gave the Angels another distinction: theirs had been the longest (over 1,600 miles) and largest airlift in history.

The 511th PIR sent out patrols to evaluate the area, including Yokohama’s docks, the bombed-out city of Kawasaki, and up the Tama River towards Tokyo. The 188th PIR and 187th GIR patrolled Hayama and Misaki then along Sagami Bay, only to report that women and children ran and hid at their approach while men waved or saluted. To their surprise, the Angels discovered that rumors had spread that American paratroopers were blood-thirsty murderers and rapists.

Back in Yokohama, while the Angels of General MacArthur’s Honor Guard dined outside the New Grand Hotel on field rations, MacArthur enjoyed steak in the hotel dining room. When someone suggested he have the food checked for poison, MacArthur laughed and replied, “This is a good steak, and I don’t intend to share it with anyone!”

During the next evening’s dinner (August 31, Z+1), an aide announced the presence of Gen. Jonathan Wainwright who had stayed to command Corregidor’s defenses after President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to Australia in 1942. CO of the 511th’s Honor Guard Lieutenant Ralph Ermatinger watched the frail Wainwright enter the room and lean on a cane that MacArthur had given him before the war. Wainwright spent three years as a POW believing that he was seen as a failure in the States due to his surrender, but rising to great his old friend, MacArthur warmly explained to the general that he was viewed as a hero, adding, “Why, Jim, your old corps is yours when you want it.”

A moved Wainwright managed to whisper, “General…” Several Honor Guard members stationed outside the building remember the two Japanese citizens who committed suicide by hand grenades shortly thereafter.

The First Flag Raised Over Tokyo

While I will skip the topic of the Surrender Ceremony onboard the U.S.S. Missouri for now, there is one related event that I'd like to share before I close. The day after the Surrender Ceremony, September 3 (Z+4), the 11th Airborne’s twenty-three-year-old Lieutenant Bernard “Bud” Stapleton of Syracuse, NY, and photographer Captain Morton Sontheimer of San Francisco, CA decided to head into off-limits Tokyo “on a lark” to poke the bear.

While I will skip the topic of the Surrender Ceremony onboard the U.S.S. Missouri for now, there is one related event that I'd like to share before I close. The day after the Surrender Ceremony, September 3 (Z+4), the 11th Airborne’s twenty-three-year-old Lieutenant Bernard “Bud” Stapleton of Syracuse, NY, and photographer Captain Morton Sontheimer of San Francisco, CA decided to head into off-limits Tokyo “on a lark” to poke the bear.

“Our first stunt was to walk around the Tokyo streets unarmed,” Sontheimer reported. “Just to see what the people would do. They stared after us for blocks and when we went into a department store all business in the place stopped. We pretended not to notice, but, of course, it was a great show.”

After studying all the Japanese flags in the city, the two Angels decided that an American flag needed to be flown so they climbed to the top of the Nippon News Building. Stapleton, a former radio announcer, then raised the first American flag over Tokyo as Captain Sontheimer used his camera to record the moment (see photo to the right). Believing the photo would never make it past the military censors, Sontheimer then sent the image on, carefully leaving his own name out of it but identifying Stapleton.

Ironically, Bud's cousin Don McInerney was on the Battleship USS Iowa where Sontheimer's film was processed. Believing he was doing his cousin a favor, Don allowed the photo of Bud to clear the censors and the image soon appeared on the front page of nearly every newspaper in the country. The Angel's Lieutenant Stapleton was in instant celebrity and he received messages from around the world, including from the Queen of England.

General MacArthur, however, was far less pleased and summoned the Angel for a “chat” as the lowly Lieutenant had upstaged his own planned flag raising ceremony that was to happen a few days later.

“You cannot imagine what it is like to be chewed out by a five-star general,” Bud deadpanned.

I hope you enjoyed this little snippet into the history of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment (and the 11th Airborne Division as a whole). We are laboring to constantly update this regimental history website with photos, videos, blog posts and interviews, so check back often.

To learn more about the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of our books on the Angels: