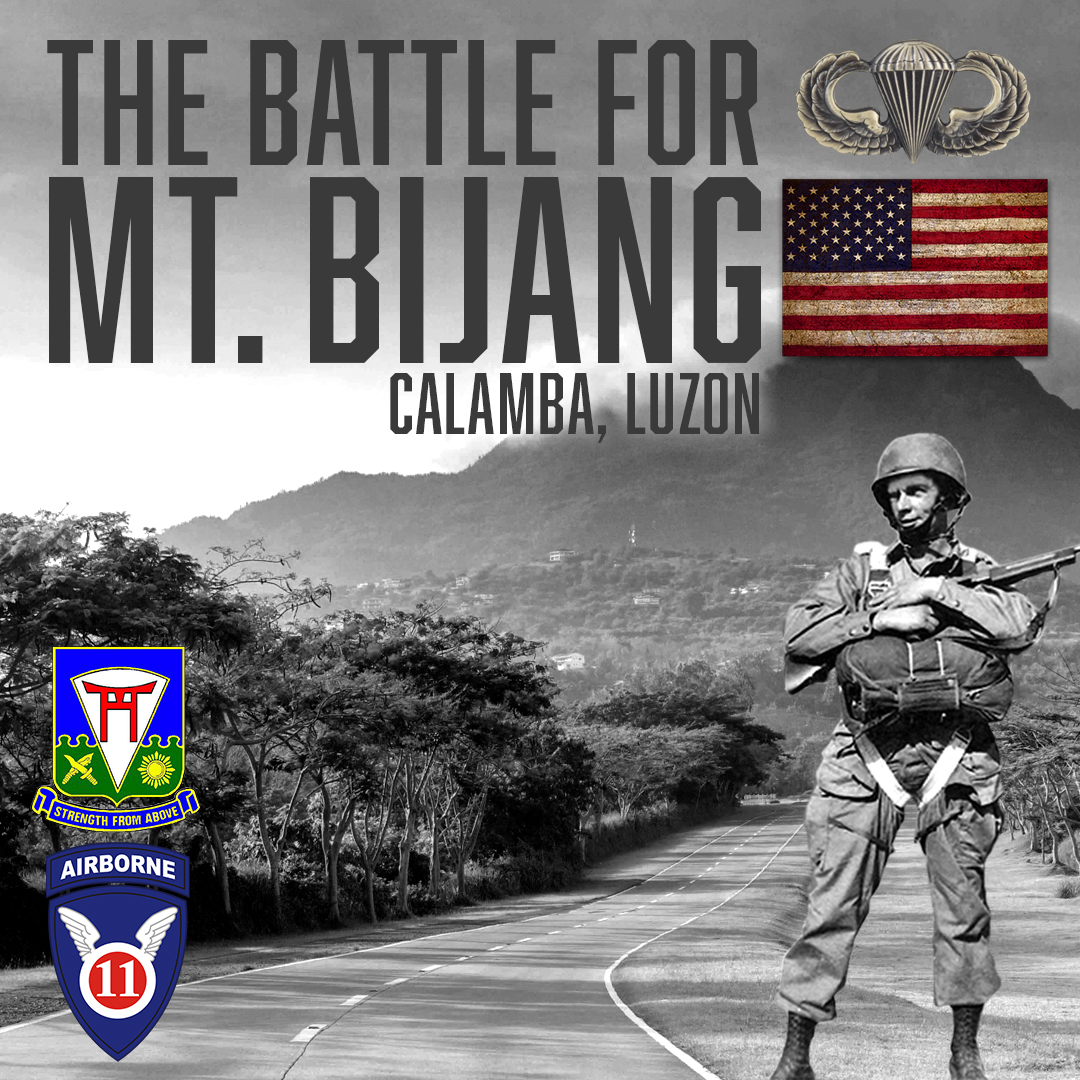

The Battle for Luzon's Mount Bijang (also Bijiang), located about 40 miles south-east of Manila is one of those obscure combat engagements that the world has passed over simply because World War II was full of tens of thousands of such operations on land, the seas and in the air.

As any military historian (or even casual student) can tell you, these battles were often fought by men, frequently young men, who found deep wells of courage in the heat of battle in a mixture of adrenaline, duty, will, and an unrelenting desire to do their best for their buddies.

The Battle for Mt. Bijang is the story of one understrength parachute company in their fight to take and retain what their company commander called, "an insignificant piece of real estate" against an estimated 300 Japanese defenders. I have heard from the paratroopers who were there, including that company commander, and from my own grandfather, 1LT Andrew Carrico III who was serving as Company Executive Officer at the time and was wounded so badly that some in D Company thought he was killed. The Battle for Mt. Bijang was one of those "small-unit operations" that displays the effects of superb leadership, skilled NCOs, determined frontline fighters and one unit's unwillingness to let each other down.

The Battle for Mt. Bijang is the story of one understrength parachute company in their fight to take and retain what their company commander called, "an insignificant piece of real estate" against an estimated 300 Japanese defenders. I have heard from the paratroopers who were there, including that company commander, and from my own grandfather, 1LT Andrew Carrico III who was serving as Company Executive Officer at the time and was wounded so badly that some in D Company thought he was killed. The Battle for Mt. Bijang was one of those "small-unit operations" that displays the effects of superb leadership, skilled NCOs, determined frontline fighters and one unit's unwillingness to let each other down.

Battle Background

On February 3, 1945, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment dropped on Luzon's Tagaytay Ridge just south of Manila, then pushed north up into the city. Grandpa's D Company, the same unit that fought the Battle for Mt. Bijang, was selected to spearhead the 11th Airborne Division's drive into Manila and Grandpa explained, "Here we are, a little old airborne division with its 8,000 men attacking Manila from the South and the 1st Calvary Division with its 20,000 men attacking from the North and (my) 1st Platoon, D Company out in front of everybody! Quite an Experience."

He then chuckled and said, "My squad leaders all asked, 'Why do we get all the dirty jobs?!'"

The Battle for Manila would prove to be bloody for Major-General Joseph May Swing's understrength 11th Airborne Division, including D Company which would be the first Angels to encounter the enemy at Imus, just outside Manila proper (a story for another day!). In 1949, COL Edward H. "Slugger" Lahti, CO of the 511th PIR, explained that the regiment's 2nd Battalion (which included D Company) had landed on Tagaytay Ridge on February 3, 1945 with 502 men. By February 10, one week later, the battalion was down to just 187 effective officers and enlisted men.

On February 10, the battle-worn men of D Company were given a break from the lines and twenty-three-year-old Captain Stephen Edward "Rusty" Cavanaugh selected an assembly point for D Company several hundred yards to the rear near the Parañaque Bridge where they could clean up and get a hot meal. As his troopers moved back, the fatigued captain grew frustrated with what appeared to be a delay in assembly. Nerves frayed from a week of combat (during which he slept very little), Cavanaugh chewed out his new 1SGT Paul R. Farnsworth for the men’s sluggishness.

With a pained look in his eyes, Farnsworth quietly replied, “Sir, that’s all there is.” Everyone else was gone.

Paul’s words hit Rusty like a sledgehammer. The young captain, who would years later serve as Chief SOG in Vietnam, later noted, “Between the 5th and the 10th of February D Company sustained thirty-eight men killed or wounded. This was almost a third of the company strength...”

Remembering those who remained, most of whom were sick with one illness or another, Rusty noted, "These were exceptional soldiers who I never fully appreciated until many years later while serving with other units in other theaters of operation."

Pondering the vicious fighting he had experienced with D Company on Leyte and Luzon, and all the friends he lost, Grandpa/1LT Andrew Carrico wrote to a young schoolgirl many decades later, "Tell your parents if they want to get a good idea of what war was like, go see the movie, 'Saving Private Ryan.'"

The Lipa Corridor

Over the next month or so, a lot of D Company's early casualties from the Manila campaign made their way back to the company (with or without being discharged from the hospital) and Captain Cavanaugh was glad to have several experienced veterans back in his ranks. The fights for Nichols Field, Fort McKinley, Mabato Point, etc. between February 10 and March 12 had inflicted further losses across the division, and with Manila secured, the 11th Airborne was tasked with clearing Southern Luzon, especially the Macolod and Lipa areas so the direction of their drive shifted to the southeast. Although MG Swing’s new T/O authorized 12,000 men, the division was far below that. Even with the attachment of the 158th Regimental Combat Team, “the Bushmasters”, under one-eyed Gen. Hanford “Jack” MacNider, the Angels only numbered about 9,000 in comparison to Japan’s estimated 28,000 men in their assigned zones, familiar odds for Swing’s men.

At the time, the 11th Airborne Division was on XIV Corps' right flank with the Angels' own right flank on Laguna de Bay. To their southwest lay the enemy's 15,380-man Shimbu Shudan Force southwest of Manila which consisted mainly of Japan’s 31st Infantry Division and to their south the 13,000-man Fuji Heidan Force, mainly of the enemy’s 8th Infantry Division. If these two groups were eliminated, it would help secure the port of Batangas on the shore of Manila Bay, thus providing the Allies a landing area for future troop movements and resupply.

As such, two weeks after the division's famous raid on the Los Baños internment camp (February 23, 1945) wherein over 2,100 civilians were rescued from behind enemy lines, CPT Cavanaugh’s exhausted D Company went back into regimental reserve after patrolling Mamatid on March 7 (X+35) then calling in air strikes on enemy troop concentrations and supply dumps around Santa Clara on March 8 (X+36). Two days later Dog Company found themselves in the town of Real at an abandoned sugar mill at Sugar Central’s Calamba estate, or what was left of it (pictured right), along Highway 1 (now Route 3). After the hells of combat in Manila, the commercial installation, while heavily damaged, was a place to rest.

As such, two weeks after the division's famous raid on the Los Baños internment camp (February 23, 1945) wherein over 2,100 civilians were rescued from behind enemy lines, CPT Cavanaugh’s exhausted D Company went back into regimental reserve after patrolling Mamatid on March 7 (X+35) then calling in air strikes on enemy troop concentrations and supply dumps around Santa Clara on March 8 (X+36). Two days later Dog Company found themselves in the town of Real at an abandoned sugar mill at Sugar Central’s Calamba estate, or what was left of it (pictured right), along Highway 1 (now Route 3). After the hells of combat in Manila, the commercial installation, while heavily damaged, was a place to rest.

But not for long. On March 10 (X+38 for the division), after moving Grandpa’s 1st Platoon of D-511 to How Company’s position, LTC Edward Lahti ordered H Company to recon up Mt. Bijang, the highest peak in the area which lay just northeast of the Ayala Greenfield Golf Course and is now partially covered by the Ayala Greenfield Estates. While CPT Cavanauagh called it "insignificant", the truth is that Mt. Bijang, while not large in comparison to the nearby Mt. Makiling range, did control the surrounding area and left a two-mile stretch of Highway 1 (and therefore troop and civilian movement) vulnerable to artillery fire. You can see its position on Google Maps here.

The 511th's paratroopers at Sugar Central could see Bijang in the distance as it was only about 7,000 yards to their south. The hill's thick foliage made troop observation difficult and the surrounding approaches were cultivated fields whose flat surfaces gave the Japanese a clear view of any Allied movements. The enemy on Bijang's crest could see all the way to Laguna de Bay to their northeast, including the Los Banos highway (now the Manila South Road / National Highway), and even watch the 511th's CP at Sugar Central.

There was an improved road running from that CP to Mt. Bijang's base, BUT running just outside the hill's northern and western edges lies what the Angels called "Brown Creek", a natural barrier that would pose a problem for the 511th PIR's efforts to push south. The Japanese had blown the only bridge (at the time) across the gully which meant that the paratroopers' efforts to clear the hill would have be done without close armored support. It also meant that any approaches made towards the hilltop would have to be made on foot.

Combat intelligence indicated that a positions held on or near Mt. Bijang was occupied by one reinforced rifle company, BUT there was concern that the Japanese could reinforce Bijang by boat across Laguna de Bay as well as bring in small groups from surrounding areas to the southwest, south and southeast. The 511th's planners believed that the sooner an attack could be made, the better. Again, the enemy could see their camp at Sugar Central and must have assumed that the paratroopers would soon come there way. As such, the longer the Angels took to make their attack, the longer the Japanese would have to strengthen their hilltop defenses and improve their fields of fire.

Again, the 511th PIR's H Company was ordered to recon Mt. Bijang's heights on March 10, 1945, but at around 1200 their small patrol ran into heavy resistance and suffered six casualties before pulling back without even obtaining a visual on the enemy. Clearly the enemy had dug in on Bijang as anticipated.

On March 11 (X+39), LTC Lahti sent CPT Robert Kliewer’s I Company and a group of supporting Filipino guerillas up Bijang's western slopes to find and push the elusive Japanese off the hilltop, but the ascending Angels found themselves facing well-hidden spider holes and reinforced field positions that even air strikes could not eliminate. I Company pressed the assault but suffered 4 KIA and 4 WIA while their attached guerillas had 2 KIA and 2 WIA and the attackers were forced to withdraw.

No wonder a regimental journal later noted, "Mount Bijang was one of the best fortified enemy positions the Regiment ever attacked", and if you've read my book WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II, then you'll understand just how strong that statement is considering how bad the Leyte campaign and how brutal the battle for Manila were.

After I Company's CPT Kliewer reported to Regimental CP, LTC Lahti sent word to Cpt. Cavanaugh to prepare D Company for action before ordering their artillery and P-38 air support to bombard the Japanese on Bijang into submission for two days while possible tank approaches were scouted (again, none were found). A division history states that the barrages from the 457th Field Artillery Battalion (light) and 472nd Field Artillery Battalion (medium) “blew the top off the hill”, but unfortunately it was the wrong hill, as the 511th's D Company would soon discover.