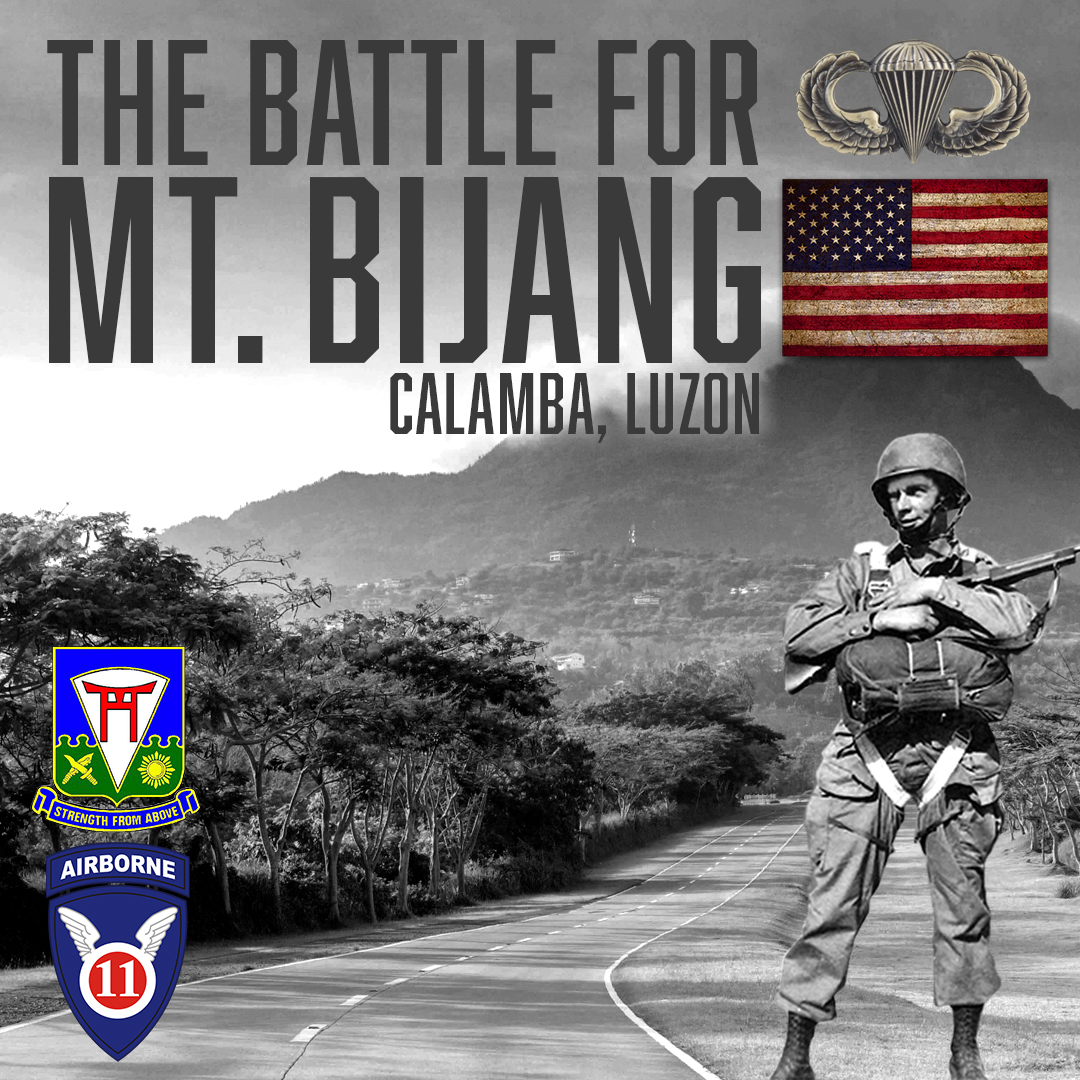

The Battle for Luzon's Mount Bijang (also Bijiang), located about 40 miles south-east of Manila is one of those obscure combat engagements that the world has passed over simply because World War II was full of tens of thousands of such operations on land, the seas and in the air.

As any military historian (or even casual student) can tell you, these battles were often fought by men, frequently young men, who found deep wells of courage in the heat of battle in a mixture of adrenaline, duty, will, and an unrelenting desire to do their best for their buddies.

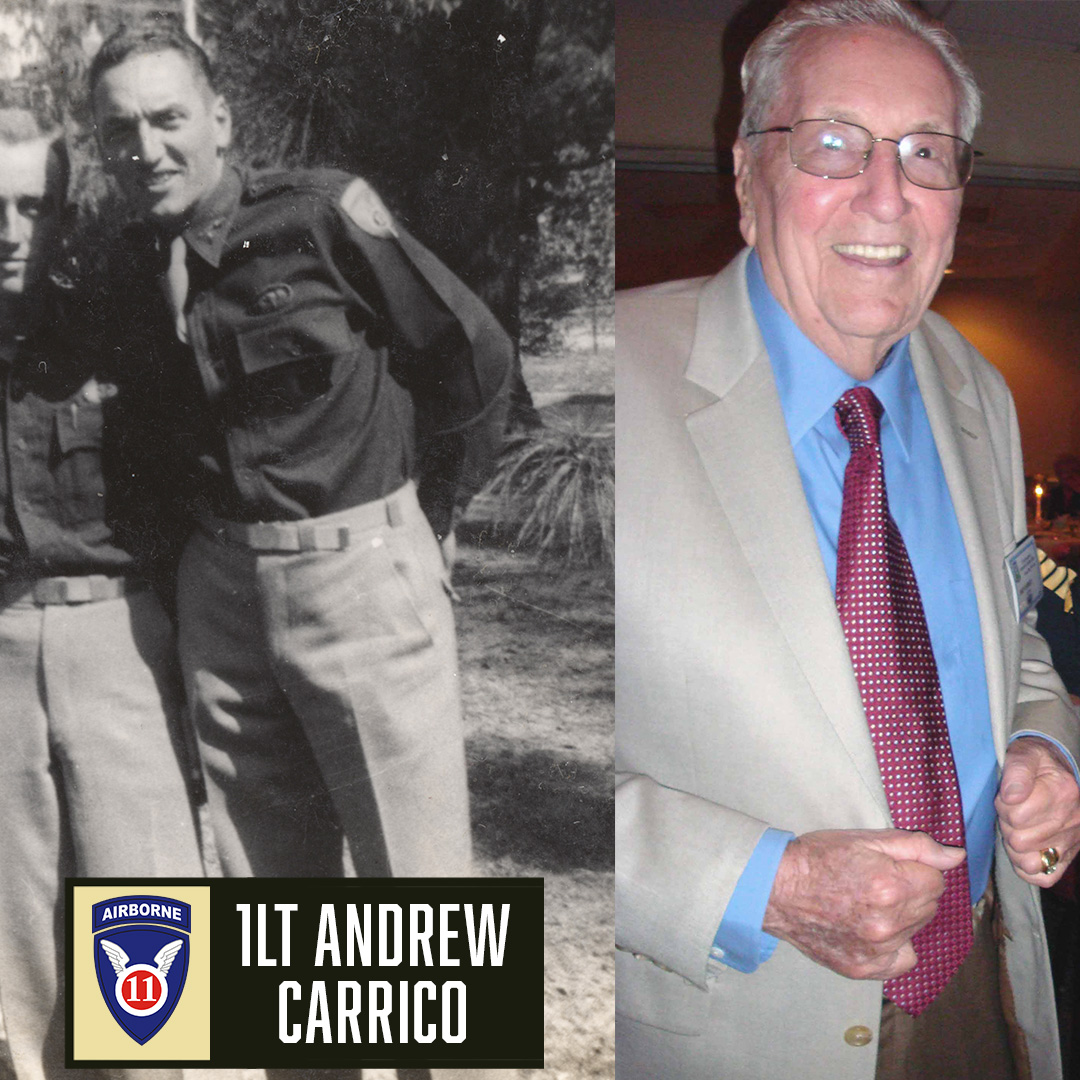

The Battle for Mt. Bijang is the story of one understrength parachute company in their fight to take and retain what their company commander called, "an insignificant piece of real estate" against an estimated 300 Japanese defenders. I have heard from the paratroopers who were there, including that company commander, and from my own grandfather, 1LT Andrew Carrico III who was serving as Company Executive Officer at the time and was wounded so badly that some in D Company thought he was killed. The Battle for Mt. Bijang was one of those "small-unit operations" that displays the effects of superb leadership, skilled NCOs, determined frontline fighters and one unit's unwillingness to let each other down.

The Battle for Mt. Bijang is the story of one understrength parachute company in their fight to take and retain what their company commander called, "an insignificant piece of real estate" against an estimated 300 Japanese defenders. I have heard from the paratroopers who were there, including that company commander, and from my own grandfather, 1LT Andrew Carrico III who was serving as Company Executive Officer at the time and was wounded so badly that some in D Company thought he was killed. The Battle for Mt. Bijang was one of those "small-unit operations" that displays the effects of superb leadership, skilled NCOs, determined frontline fighters and one unit's unwillingness to let each other down.

Battle Background

On February 3, 1945, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment dropped on Luzon's Tagaytay Ridge just south of Manila, then pushed north up into the city. Grandpa's D Company, the same unit that fought the Battle for Mt. Bijang, was selected to spearhead the 11th Airborne Division's drive into Manila and Grandpa explained, "Here we are, a little old airborne division with its 8,000 men attacking Manila from the South and the 1st Calvary Division with its 20,000 men attacking from the North and (my) 1st Platoon, D Company out in front of everybody! Quite an Experience."

He then chuckled and said, "My squad leaders all asked, 'Why do we get all the dirty jobs?!'"

The Battle for Manila would prove to be bloody for Major-General Joseph May Swing's understrength 11th Airborne Division, including D Company which would be the first Angels to encounter the enemy at Imus, just outside Manila proper (a story for another day!). In 1949, COL Edward H. "Slugger" Lahti, CO of the 511th PIR, explained that the regiment's 2nd Battalion (which included D Company) had landed on Tagaytay Ridge on February 3, 1945 with 502 men. By February 10, one week later, the battalion was down to just 187 effective officers and enlisted men.

On February 10, the battle-worn men of D Company were given a break from the lines and twenty-three-year-old Captain Stephen Edward "Rusty" Cavanaugh selected an assembly point for D Company several hundred yards to the rear near the Parañaque Bridge where they could clean up and get a hot meal. As his troopers moved back, the fatigued captain grew frustrated with what appeared to be a delay in assembly. Nerves frayed from a week of combat (during which he slept very little), Cavanaugh chewed out his new 1SGT Paul R. Farnsworth for the men’s sluggishness.

With a pained look in his eyes, Farnsworth quietly replied, “Sir, that’s all there is.” Everyone else was gone.

Paul’s words hit Rusty like a sledgehammer. The young captain, who would years later serve as Chief SOG in Vietnam, later noted, “Between the 5th and the 10th of February D Company sustained thirty-eight men killed or wounded. This was almost a third of the company strength...”

Remembering those who remained, most of whom were sick with one illness or another, Rusty noted, "These were exceptional soldiers who I never fully appreciated until many years later while serving with other units in other theaters of operation."

Pondering the vicious fighting he had experienced with D Company on Leyte and Luzon, and all the friends he lost, Grandpa/1LT Andrew Carrico wrote to a young schoolgirl many decades later, "Tell your parents if they want to get a good idea of what war was like, go see the movie, 'Saving Private Ryan.'"

The Lipa Corridor

Over the next month or so, a lot of D Company's early casualties from the Manila campaign made their way back to the company (with or without being discharged from the hospital) and Captain Cavanaugh was glad to have several experienced veterans back in his ranks. The fights for Nichols Field, Fort McKinley, Mabato Point, etc. between February 10 and March 12 had inflicted further losses across the division, and with Manila secured, the 11th Airborne was tasked with clearing Southern Luzon, especially the Macolod and Lipa areas so the direction of their drive shifted to the southeast. Although MG Swing’s new T/O authorized 12,000 men, the division was far below that. Even with the attachment of the 158th Regimental Combat Team, “the Bushmasters”, under one-eyed Gen. Hanford “Jack” MacNider, the Angels only numbered about 9,000 in comparison to Japan’s estimated 28,000 men in their assigned zones, familiar odds for Swing’s men.

At the time, the 11th Airborne Division was on XIV Corps' right flank with the Angels' own right flank on Laguna de Bay. To their southwest lay the enemy's 15,380-man Shimbu Shudan Force southwest of Manila which consisted mainly of Japan’s 31st Infantry Division and to their south the 13,000-man Fuji Heidan Force, mainly of the enemy’s 8th Infantry Division. If these two groups were eliminated, it would help secure the port of Batangas on the shore of Manila Bay, thus providing the Allies a landing area for future troop movements and resupply.

As such, two weeks after the division's famous raid on the Los Baños internment camp (February 23, 1945) wherein over 2,100 civilians were rescued from behind enemy lines, CPT Cavanaugh’s exhausted D Company went back into regimental reserve after patrolling Mamatid on March 7 (X+35) then calling in air strikes on enemy troop concentrations and supply dumps around Santa Clara on March 8 (X+36). Two days later Dog Company found themselves in the town of Real at an abandoned sugar mill at Sugar Central’s Calamba estate, or what was left of it (pictured right), along Highway 1 (now Route 3). After the hells of combat in Manila, the commercial installation, while heavily damaged, was a place to rest.

As such, two weeks after the division's famous raid on the Los Baños internment camp (February 23, 1945) wherein over 2,100 civilians were rescued from behind enemy lines, CPT Cavanaugh’s exhausted D Company went back into regimental reserve after patrolling Mamatid on March 7 (X+35) then calling in air strikes on enemy troop concentrations and supply dumps around Santa Clara on March 8 (X+36). Two days later Dog Company found themselves in the town of Real at an abandoned sugar mill at Sugar Central’s Calamba estate, or what was left of it (pictured right), along Highway 1 (now Route 3). After the hells of combat in Manila, the commercial installation, while heavily damaged, was a place to rest.

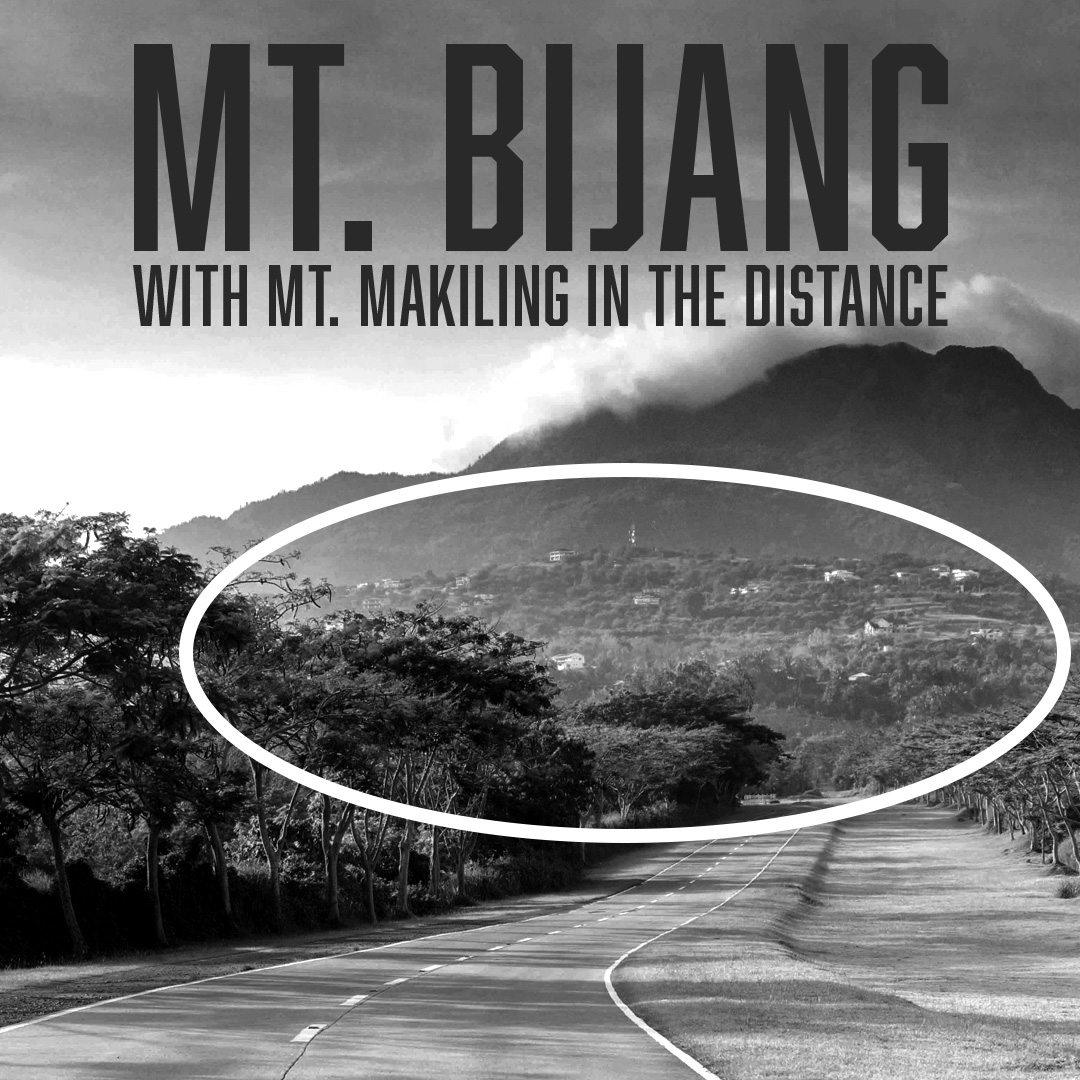

But not for long. On March 10 (X+38 for the division), after moving Grandpa’s 1st Platoon of D-511 to How Company’s position, LTC Edward Lahti ordered H Company to recon up Mt. Bijang, the highest peak in the area which lay just northeast of the Ayala Greenfield Golf Course and is now partially covered by the Ayala Greenfield Estates. While CPT Cavanauagh called it "insignificant", the truth is that Mt. Bijang, while not large in comparison to the nearby Mt. Makiling range, did control the surrounding area and left a two-mile stretch of Highway 1 (and therefore troop and civilian movement) vulnerable to artillery fire. You can see its position on Google Maps here.

The 511th's paratroopers at Sugar Central could see Bijang in the distance as it was only about 7,000 yards to their south. The hill's thick foliage made troop observation difficult and the surrounding approaches were cultivated fields whose flat surfaces gave the Japanese a clear view of any Allied movements. The enemy on Bijang's crest could see all the way to Laguna de Bay to their northeast, including the Los Banos highway (now the Manila South Road / National Highway), and even watch the 511th's CP at Sugar Central.

There was an improved road running from that CP to Mt. Bijang's base, BUT running just outside the hill's northern and western edges lies what the Angels called "Brown Creek", a natural barrier that would pose a problem for the 511th PIR's efforts to push south. The Japanese had blown the only bridge (at the time) across the gully which meant that the paratroopers' efforts to clear the hill would have be done without close armored support. It also meant that any approaches made towards the hilltop would have to be made on foot.

Combat intelligence indicated that a positions held on or near Mt. Bijang was occupied by one reinforced rifle company, BUT there was concern that the Japanese could reinforce Bijang by boat across Laguna de Bay as well as bring in small groups from surrounding areas to the southwest, south and southeast. The 511th's planners believed that the sooner an attack could be made, the better. Again, the enemy could see their camp at Sugar Central and must have assumed that the paratroopers would soon come there way. As such, the longer the Angels took to make their attack, the longer the Japanese would have to strengthen their hilltop defenses and improve their fields of fire.

Again, the 511th PIR's H Company was ordered to recon Mt. Bijang's heights on March 10, 1945, but at around 1200 their small patrol ran into heavy resistance and suffered six casualties before pulling back without even obtaining a visual on the enemy. Clearly the enemy had dug in on Bijang as anticipated.

On March 11 (X+39), LTC Lahti sent CPT Robert Kliewer’s I Company and a group of supporting Filipino guerillas up Bijang's western slopes to find and push the elusive Japanese off the hilltop, but the ascending Angels found themselves facing well-hidden spider holes and reinforced field positions that even air strikes could not eliminate. I Company pressed the assault but suffered 4 KIA and 4 WIA while their attached guerillas had 2 KIA and 2 WIA and the attackers were forced to withdraw.

No wonder a regimental journal later noted, "Mount Bijang was one of the best fortified enemy positions the Regiment ever attacked", and if you've read my book WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II, then you'll understand just how strong that statement is considering how bad the Leyte campaign and how brutal the battle for Manila were.

After I Company's CPT Kliewer reported to Regimental CP, LTC Lahti sent word to Cpt. Cavanaugh to prepare D Company for action before ordering their artillery and P-38 air support to bombard the Japanese on Bijang into submission for two days while possible tank approaches were scouted (again, none were found). A division history states that the barrages from the 457th Field Artillery Battalion (light) and 472nd Field Artillery Battalion (medium) “blew the top off the hill”, but unfortunately it was the wrong hill, as the 511th's D Company would soon discover.

"That Hill": D Company's Recon and Approach

On March 12 (X+40), at about 1600, CPT Cavanaugh (pictured right) was summoned to COL Lahti’s Sugar Central CP to converse with Regimental S-3, MAJ William F. Frick, before meeting with Lahti atop the roof where the Mt. Bijang bombardments could be observed. Studying the mountain and Mt. Makiling to the east, Cavanaugh and Big Ed discussed the need to clear the enemy off the mountains and I Company’s failure to do so. They also discussed the fact that their maps were considered fairly inaccurate and that no aircraft were available for aerial photography. Cavanaugh would have to do a visual reconnaissance on his own.

On March 12 (X+40), at about 1600, CPT Cavanaugh (pictured right) was summoned to COL Lahti’s Sugar Central CP to converse with Regimental S-3, MAJ William F. Frick, before meeting with Lahti atop the roof where the Mt. Bijang bombardments could be observed. Studying the mountain and Mt. Makiling to the east, Cavanaugh and Big Ed discussed the need to clear the enemy off the mountains and I Company’s failure to do so. They also discussed the fact that their maps were considered fairly inaccurate and that no aircraft were available for aerial photography. Cavanaugh would have to do a visual reconnaissance on his own.

Departing Lahti’s CP with a fragmentary order for attack, Rusty returned to Dog Company’s area and gathered Grandpa/1LT Andrew Carrico, now Cavanaugh's Executive Officer, and the platoon leaders to discuss the mission. Rusty then spoke with 2nd Battalions’ LTC Frank S. “Hacksaw” Holcombe to apprise him of and review the situation. While Grandpa, the platoon leaders and their NCOs checked equipment and drew out ammo and 1/3 K-rations, Rusty returned to Lahti’s CP to coordinate plans with "Big Ed" and I Company's CPT Kliewer.

COL Lahti then leant the two company commanders his personal jeep and during a break in the shelling and bombing, Rusty and CPT Kliewer plus 2/511’s XO CPT Julius J. Toth used the jeep to survey enemy positions and potential avenues of approach. Their route took them down Highway 1, through Real then south-west on the Santo Tomas-Lipa Highway then back to Sugar Central.

The plan was for I Company to again push up the hill, this time using the northern slopes, towards the crest while D Company marched up from another direction. Since Lahti left the final choice of line of assault up to him, Rusty chose a new southern-slope route since he agreed with CPT Kliewer that the western slopes were the worst for approach. Noticing that Mt. Bijang sat just in front of Mt. Makiling and the draws between the two presented a more protected avenue of approach, Rusty decided to move D Company up the hill’s southern slope using its small ridges for concealment as there was very little foliage on the incline.

It was assumed that I Company would be in position to call for the pre-planned artillery fire first and that D Company would assist in the attack on the crest (this would not prove to be the case). Upon capture of the hilltop, Rusty and D Company were to then protect I Company's organization and deployment on the crest, then return to Regimental reserve. Captain Cavanaugh was specifically told that his company would return to the regimental perimeter that night, so he elected to have his men leave their heavier packs at their camp (for most, this included their entrenching tools, a decision that would soon come back to haunt them) and only one 61-mm mortar with 24 rounds would be carried on the assault.

Cavanaugh then spoke with the regiment’s artillery liaison officer who promised 105mm howitzer support before returning to check on D Company’s preparations. He discovered that since the regimental communication's officer had gathered all the SCR-536 radios to repair them, his radioman PFC Roy C. Lipanovich would only have an SCR-300 to use (the artillery liaison also has a radio for communication).

Rusty said of the attached artillery liaison, a lieutenant, "This young officer proved to be a great artilleryman, and showed great courage during the entire operation."

The next day, March 13 (X+41), after breakfast Rusty ordered his 95 men (including some new replacements) to move out down the dirt road to their Line of Departure, about two-and-a-half miles away. Item Company had already left at 0715 and the paratroopers felt some comfort during their "hike" after watching twelve P-38s drop 100-pound high explosive bombs on suspected enemy positions to their front.

Moving in a column of platoons, with one file on each side of the road, CPT Cavanaugh had 3rd Platoon then Company Headquarters lead off with the mortar squad while Grandpa’s old 1st Platoon followed about fifty yards behind. In the already ninety-degree heat, 2nd Platoon brought up the rear with 5-10 yards between each trooper and everyone was surprised when 2nd Battalion's Executive Officer MAJ John R. Cook caught up with D Company in his jeep and told CPT Cavanaugh that he would join them in their push up Bijang's southern slope. It was a decision that would soon place him squarely in harm's way.

Moving in a column of platoons, with one file on each side of the road, CPT Cavanaugh had 3rd Platoon then Company Headquarters lead off with the mortar squad while Grandpa’s old 1st Platoon followed about fifty yards behind. In the already ninety-degree heat, 2nd Platoon brought up the rear with 5-10 yards between each trooper and everyone was surprised when 2nd Battalion's Executive Officer MAJ John R. Cook caught up with D Company in his jeep and told CPT Cavanaugh that he would join them in their push up Bijang's southern slope. It was a decision that would soon place him squarely in harm's way.

Cavanaugh, radioman PFC Roy C. Lipanovich, and the company runners traveled at the head of 1st Platoon before Rusty ordered a rest at 0850. Fifteen minutes later Dog Company was back on its feet and Rusty and his Company HQ entourage moved up to march with 3rd Platoon as they crossed open fields. As they approached the hill's edges, friendly artillery began roaring in from the north.

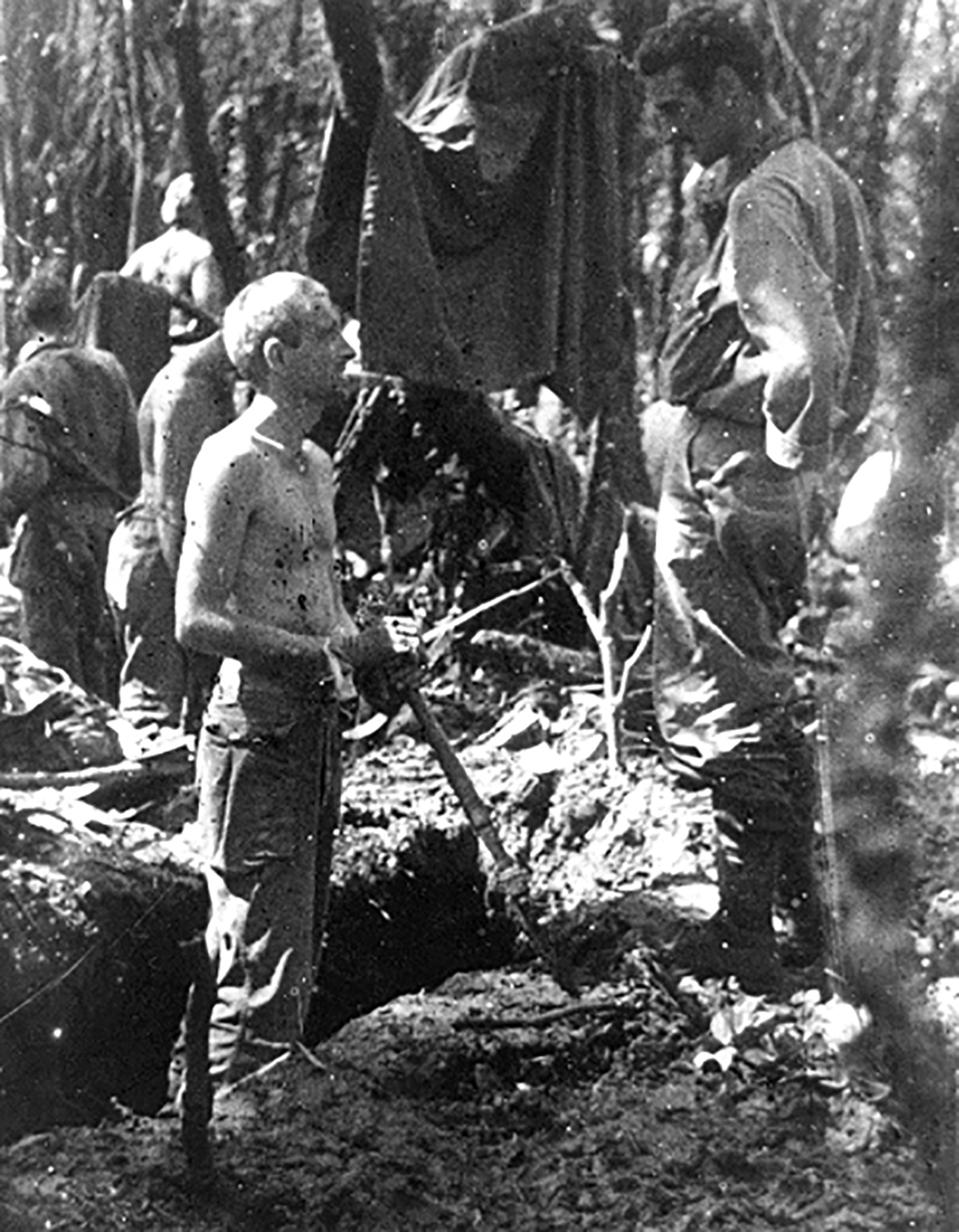

"(Our artillery) fired on the mountain with heavy shells for hours, I believe, before starting our climb upwards," noted Pfc. Elmer C. "Chuck" Hudson "Shells were still coming in when we got to the foot of the mountain. I remember the shelling was so close that shrapnel was raining down on our steel helmets. After the shelling stopped, we moved forward up the mountain."

Their pace quickened when the faint sounds of rifle and machine gun fire were heard around 0945. I Company had found the enemy on their own approach so with a reminder to use the ridgeline for cover, CPT Cavanaugh’s sweating paratroopers began their own long hike up the hill. With scouts leading the way (one-hundred yards ahead, still in visual contact), 3rd and 1st Platoon traveled abreast while 2nd Platoon brought up the rear. A little before 1200, 1st Platoon flattened when a small enemy outpost was discovered and SGT William L. Dubes and his two scouts killed the sentries. Bill had just returned from a Hollandia hospital and as Executive Officer Grandpa made the trusted veteran 1st Squad Leader, 1st Platoon.

As Bill led the column onward, Grandpa/1LT Carrico and Rusty/CPT Cavanaugh shared a quiet look. What else lay in store up the hill?

Contact! Pushing Upwards

3rd Platoon, in the lead, continued upwards for another two hundreds yards or so when rifle and automatic weapons fire brought the Angels to a stop. The platoon's three squads spread out into a firing line and CPT Cavanaugh moved up to study the situation.

3rd Platoon, in the lead, continued upwards for another two hundreds yards or so when rifle and automatic weapons fire brought the Angels to a stop. The platoon's three squads spread out into a firing line and CPT Cavanaugh moved up to study the situation.

"Almost immediately we were taken under fire by what I assumed was an enemy picket line and we had one man killed," Rusty said. "We continued advancing against sporadic enemy rifle fire and sustained another casualty."

The first man hit, and killed, was scout, PVT Raymond “Red” Cegiacnik, who was one hundred yards in front of the main column with SGT Bill Dubes when a Japansese machine gun opened fire. Dubes hit the dirt (he even ate some it) and when the enemy began firing in a different direction, Bill looked up at his comrade in shock.

(Cegiacnik) was in bad shape," he noted. "It was a miracle he was on his feet. The machine gun burst had torn away his lower jawbone, his tongue was hanging out, and he was bleeding profusely. I was covered in blood just trying to save him. Our medics tried… but he had lost too much blood."

"From then on there was fierce fighting all the way to the top of Mt. Bijang for what seemed like hours," remembered PFC “Chuck” Hudson.

Rusty noticed that the enemy was firing from 3rd Platoon’s left and center, so he ordered 1st Platoon to flank the enemy by traversing 3rd Platoon’s right. This took them back down through 2nd Platoon before they moved up a concealed draw off to the right where a runner soon reported to CPT Cavanaugh that the platoon was "Held up by enemy fire from the front and left." Rusty sent the runner back with orders to hold position and eliminate the threat.

Cavanaugh then spoke with the artillery liaison officer who called in a fire mission from Ginger 6 (which showered SGT Dubes and the wounded PFC Cegiacnik with dirt), but Rusty wanted to first determine the enemy’s flank and move 3rd Platoon back from the target area. Turning to his XO, Rusty sent Grandpa/LT Carrico to order 3rd Platoon to disengage and move to 1st Platoon’s far right flank which would give the artillery a five-hundred-yard safety zone (2nd Platoon remained about 300 yards down the slope).

As his men moved to comply, Cavanaugh and Grandpa voiced mutual concern that the Japanese were only delaying the Angels while calling for reinforcements from their main positions higher up the hill. The enemy appeared to be affecting a tactical withdrawal towards the downslope-moving reinforcements, if some were indeed on the way. To find out, Rusty moved up to 1st Platoon’s right to better command the Angels’ firing line and also be in place to direct 3rd Platoon when they moved up. This new position also gave him a perfect view of their objective, or at least what he thought was their objective and he realized that the enemy had failed to take advantage of an opening to flank his men.

When a runner found Cavanaugh and said that LT Carrico and 3rd Platoon were in position, Rusty was surprised as he could not see them. The hill they were supposed to be on was to his left, but he heard 3rd Platoon off to his right. Ordering the runner to take him to the lost platoon, Cavanaugh found himself looking down forty feet at the hill he initially believed was theirs to take. That crest was, in fact, hiding their real destination upon which Cavanaugh now stood. While no one had been able to see it from the lowlands, Mt. Bijang’s true ridge was higher than assumed and three hundred yards to the south. That meant that all the previously registered artillery barrages had been of little effect on the enemy.

Lead scout PFC Michael J. Rottenberk of Chicago, IL, determined that the correct crest had been occupied by the enemy, but was now deserted and it is possible that the departed Japanese were now engaged with I Company on their own approach. Rottenberk also noticed that the summit’s rolling terrain possessed numerous low-level dikes that had been used by local farmers to grow rice. These, along with empty Japanese foxholes, would soon become lifesavers for D Company.

Michael also swore he celebrated his birthday that day (March 13), but records indicate he was born on March 15. Either way, he noted that surviving Mt. Bijang was one heck of a present.

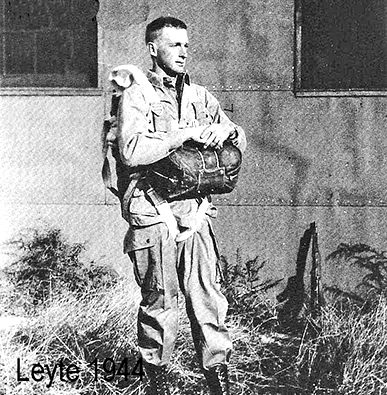

Realizing he was standing on their true objective, CPT Cavanaugh sent runners to bring up 1st and 2nd Platoons (the enemy fire on 1st Platoon had quieted). Arriving on the crest, Grandpa/1LT Carrico (pictured right) helped deploy the platoons around the flat hilltop, with 2LT James W. Osmun’s 1st Platoon on the left while an over-extended 2nd Platoon under 1LT Walter Kannely spread out on the right. Without consulting anyone, Kannely had committed one squad to evacuating the company’s two dead and four wounded, which left D Company down to around eighty men.

Realizing he was standing on their true objective, CPT Cavanaugh sent runners to bring up 1st and 2nd Platoons (the enemy fire on 1st Platoon had quieted). Arriving on the crest, Grandpa/1LT Carrico (pictured right) helped deploy the platoons around the flat hilltop, with 2LT James W. Osmun’s 1st Platoon on the left while an over-extended 2nd Platoon under 1LT Walter Kannely spread out on the right. Without consulting anyone, Kannely had committed one squad to evacuating the company’s two dead and four wounded, which left D Company down to around eighty men.

While Grandpa organized the company around the crest, CPT Cavanaugh took a quiet walk along the ridgeline with PFC Lipanovich after telling Roy to message Regiment to confirm that D Company was on the objective.

Surprisingly, Rusty then ordered his XO, my grandfather, to move back with Company HQ near 3rd Platoon to protect the rear. CPT Cavanaugh explained. “He had commanded 1st Platoon through months of combat and I had promoted him to Executive Officer to give him some respite...”

With everyone settled, a squad from 3rd Platoon was sent to pop green smoke grenades to mark their position for the assumed-to-be-approaching Item Company which D Company hoped would help them hold the hilltop. The paratroopers waited in tense silence, but instead of a friendly response the hill’s quiet was shattered by the sounds of war as enemy soldiers began firing on the 3rd Platoon squad which beat a hasty retreat to the company’s main lines.

“Where’s I Company?” the squad wondered as they reported to Grandpa/1LT Carrico who got word to Rusty. With I Company’s ETA unknown, and the enemy most certainly on the way, CPT Cavanaugh elected to position 1st Platoon to the southeast and move 2nd Platoon to the hill’s reverse slope to provide overwatch on their rear and flanks. The machine guns from each platoon were placed to cover the gaps between the three main positions and other potential avenues of attack. Positioning himself between 1st and 2nd Platoons, Rusty also placed their sole 60mm mortar to the rear of 3rd Platoon in a small depression along with the company CP and the artillery liaison officer with his radio.

In a moment of hindsight, Rusty kicked himself for ordering his men to carry such light loads as most failed to even bring entrenching tools. Before we judge his judgement, let us recall that D Company's mission had always called for an assault on, not defense of the hilltop. Bijang was supposed to be a quick one-day operation and their lighter packs allowed the Angels to move swiftly up the hillside to surprise the enemy and assist I Company in taking the hill. D Company was then supposed to help I Company setup defensive positions, then make their way back to Regiment.

Years later, Cavanaugh lamented, “The defensive position was less than desirable in that the area was too large to be fully defended with the troops I had.”

Even so, the enemy was coming, and the Angels were ready to give them hell. I Company, meanwhile, had received word that D Company was on the objective, but apparently the enemy did as well since CPT Bob Kliewer’s paratroopers watched Japanese soldiers disengage and move quickly up the slope towards Cavanaugh’s men. Kliewer tried to reposition his men to block their movement, but they were met with heavy resistance. As such, he decided to take I Company back down the hill, then move his company up the southern slopes as D Company had done.

D Company was on their own, but they would stand together no matter what came over the hill.

The Hilltop Battle

The Angels disengaged safeties and placed grenades on the ground with loosened pins. Knives were jammed in the soil for quick reach and quiet whispers of encouragement were traded between friends while officers and NCOs moved between positions with words of direction.

When the first of the enemy did arrive, the company's two machine guns and the entire 3rd Platoon opened fire and an after-action report notes, "Its effect was murderous." Everything went silent, minus one squad leader calling for a medic for his two wounded men.

Several Japanese automatic weapons then opened up on 3rd Platoon’s positions and fire was called in from the 60mm mortar squad located to the rear which delivered four rounds on target. So far, things seemed to be going in the ANgels' favor.

Then, around 1300, 3rd Platoon’s T/SGT Edwin "Ed" Leo Sorenson (pictured right), who was positioned on the company’s right flank, noticed a small dirt trail surrounded by brush and bushes that led down the hillside. Perhaps it was sixth sense, but Ed felt to throw a phosphorous grenade into the hole. He said:

Then, around 1300, 3rd Platoon’s T/SGT Edwin "Ed" Leo Sorenson (pictured right), who was positioned on the company’s right flank, noticed a small dirt trail surrounded by brush and bushes that led down the hillside. Perhaps it was sixth sense, but Ed felt to throw a phosphorous grenade into the hole. He said:

"Guess what – two or three Japanese trotted up the trail from me, no more than 30 to 50 feet away. I began shooting as they reached the top. I had two more grenades and each one I threw brought 2 or 3 more of the enemy. So, I had me a shooting gallery. The foregoing sounds very well, but I followed that with the worst sin a platoon sergeant can commit. I sent a very bright young assistant machine gunner to a position about 20 feet away from me, expecting him to be covered by the trees at the head of the draw. I was wrong, and no sooner had he put the tripod down than he was dead. I stared in disbelief and have shed tears for this young man that I did not have time for as he lay dying."

Then things got worse.

"All of a sudden, all hell broke loose," wrote medic PFC Alfred Haarof Freeman, South Dakota. “The Japs attacked us on two sides and were attempting to get behind us...”

“They really came after us,” PFC Billy Pettit added.

“It was a real battle,” Grandpa exclaimed. “They really did a good job.”

While initial reports indicated that D Company would only face a light rifle platoon or reinforced company on Mt. Bijang, Intelligence had clearly underestimated the enemy.

"We could hear them shouting and yelling, working themselves up before the attack," noted PFC Bill Dubes who would soon be wounded in the shoulder by shrapnel. "A fire had started, whether intentional or not, the smoke and ashes complicated the situation. It’s hard to know how many casualties we inflicted on them, but they hit a lot of us with mortar fire and rifle and machine gun fire."

The initial enemy barrages left D Company with eight new casualties (six wounded, two dead) which were evacuated to 2nd Platoon’s position at 1330, half an hour into the counterattack. Watching the massing bellowing Japanese, CPT Cavanaugh sent word for the artillery liaison officer to call in fire missions.

"Our artillery observer took immediate action to bring the enemy positions under fire," Rusty noted. "But the trajectory of the howitzer rounds was too flat to reach the enemy, which were within a few hundred yards of us and protected by the reverse crest of the hill… I recall the artillery shells coming in from our supporting battery passing so close over our heads that we could almost have touched them."

When the artillery liaison asked if the batteries should lower trajectory, Rusty shouted, "No, don't fire any lower! We’re scratching matches on them now."

While the Angels' artillery support roared harmlessly overhead, the attacking Japanese rained down knee-mortars at the rate of over 20-30 rounds a minute. While many were duds, the mortar rounds, only lethal within fifteen feet, inflicted several additional casualties. CPT Cavanaugh even remembered looking up from his rifle sight to watch the mortar shells arcing overhead.

"Being a mortar gunner, I knew the Japanese had zeroed in on us," remembered PFC Elmer "Chuck" Hudson. "One shell fell to the right of me and then another shell to the left. The next shell was coming down the middle. I could see several shells in the air coming right down my throat! I protected my face with my right arm, and caught five pieces of shrapnel in the arm, saving a hit to my head. This shell moved me back about 20 feet."

"I heard a solder yell, 'I have a man killed over here!'" Chuck continued. "I never did pass out, nor did I have any pain for about 10 minutes. Al Harr, our Medic, got to me and gave me a shot of morphine, and took care of me like a professional. He laid me down behind a hole and asked for my rifle, but I told him, 'I want to keep my rifle.'"

From his position between 1st and 2nd Platoons, CPT Cavanaugh opened fire on one of the enemy mortarmen 50 yards away, but without success. He noted with frustration, "I must have fired three clips at that bobbing back and I don’t think I ever hit him."

By now, D Company had been engaged with the enemy for roughly an hour so at 1400 Rusty sent a request back to Regiment via radioman PFC Roy Lipanovich for ammunition, grenades, water. The response came back at 1410 that the carrying party would leave Sugar Central at 1500 courtesy of S-4 LT Roy Stout. PFC Lipanovich then shouted for Rusty's attention once more and the young captain turned to watch an enemy bullet shockingly fly through his radioman's jaw.

Screaming for a medic, CPT Cavanaugh also learned from a runner that 1st Platoon's CO, 2LT James W. Osmun, Jr. of Hazen, Nevada, had been seriously wounded.

"Actually, he had been hit above the eye and the eye was driven out of his head and was hanging from the socket," Rusty grimly pointed out. I recently discovered that not only did 2LT Osmun survive, but the former 37th Infantry Division member went on to study at the University of Nevada before marrying Iona May Allen on January 25, 1946.

The paratroopers in 3rd and 1st Platoons could see Japanese soldiers moving behind a protective rise and some carefully crawled underneath their comrades’ fire to close in with 1st Platoon. One had managed to get a clear shot at LT Osmun before the offending enemy was devastatingly dispatched by the Angels’ grenades, including those of SGT Bill Dubes who saw the bullet exit Osmun’s left temple.

Bill noted, "That’s one time when I really thought maybe I wasn’t going to make it."

CPT Cavanaugh was wondering the same thing for his entire company. He estimated that I Company was still several hours away from joining them on the crest and the rate (and ferocity) of enemy fire, especially mortars, seemed to be increasing. In addition, the number of D Company's casualties was mounting as attested by the number of "patients" the medics were caring for near the Company's "CP" in the center.

D Company's young captain, who Brigadier General Henry Muller once said was "The ideal company commander", was doing his best to direct the intense action while his platoon and squad leaders maintained effective unit cohesion against the numerically superior enemy force. As Rusty continued to fire off orders, he became aware of a familiar presence by his side. Pausing from the action, Cavanaugh looked over and was surprised to see his XO, 1LT Andrew Carrico, at his side.

"He was six inches away," Rusty clarified.

"Carrico, you sunnavabitch!" he shouted. "What the hell are you doing here?! I told you to stay back...."

"My men are here," Grandpa yelled back, firing his M1. "I needed to be up here with my men."

While in the heat of battle Cavanaugh was initially upset, Grandpa's arrival was fortuitous as, again, his former men in 1st Platoon had just lost their new CO, 2LT Osmun. With bullets zipping and mortars exploding around them, Cavanaugh briefed Grandpa on the situation’s developments and they discussed the concern that if casualties continued to mount, they would have difficulty covering a withdrawal while evacuating the wounded. Acting quickly, Rusty was about to send Andy to assume command of 1st Platoon when a Japanese machine gun burst ripped into Grandpa's body.

"Steve! I’ve been hit!" Rusty glanced over to see 1LT Carrico bleeding profusely; the enemy bullet had torn through Grandpa’s right hand, nearly severing his ring finger, then bounced off his rifle stock as another bullet buried itself in his left shoulder.

Grandpa told me decades later, "I was lying in a Japanese foxhole firing, when suddenly I knew that I had been shot. I don’t recall a lot of pain, just 'knew I’d been hit'...." He then gestured with his four-fingered hand from right shoulder to left, pausing to point at his chin. "You can see how close that was to my head. I was pretty damn lucky."

Medic PFC Al Haar, who had been moving around the battlefield to treat their wounded, rushed to Andy's side to begin initial care. The selfless medic then got the bleeding XO to the company command post and had him rest near the seriously wounded 2LT Osmun and PFC Lipanovich, as well as several other wounded troopers.

"Al Haar… was a very busy fellow that day!" Grandpa remembered. "Al got to me, gave me a shot of morphine, and somebody (later) helped me off that mountain." It was actually 2LT Osmun; the two wounded lieutenants were later seen helping each other down the hill as D Company began their withdrawal.

CPT Cavanaugh later noted, "Our medics were doing their usual magnificent job, but there was a limit to their numbers and resources."

Of those frontline medics, CPL William R. Walter declared, "(Combat medics) are a breed of men by themselves. They do one of the most brave acts that can be done in the service, because the minute a wounded person calls for them, they go without hesitation, forgetting the fact that they are in the line of fire—the same line of fire that wounded the person they are tending to."

Back in his commandeered Japanese foxhole, CPT Cavanaugh raised his rifle to push in a fresh clip when an immense blow crashed into his head which spun him around and left the captain face down on the dike’s bank.

"I fault myself for being in an exposed position where I could not effectively command the company," he later lamented. Shaking off the haze, Rusty made sure his skull was intact.

"As I reached to recover (my helmet), I saw two holes in it, an entrance and an exit hole," he noted (he kept the helmet after the war). "How I escaped a serious if not fatal head wound, I’ll never know and except for a knot on my head as big as a pigeon’s egg my head was intact."

Grandpa explained that the bullet had entered the captain’s helmet and gone around the inner band and Rusty remarked with his typical self-effacing humor, "The fact that the round did not strike anything worthwhile while passing around my head came as no surprise to my company. They had long suspected I might be lacking in that area."

Cavanaugh’s company runner T-5 Joseph E. Signor (seen in same order in a Leyte photo to the right) crawled to his position and exclaimed, "Rusty, you’re bleeding like a stuck pig!"

Cavanaugh’s company runner T-5 Joseph E. Signor (seen in same order in a Leyte photo to the right) crawled to his position and exclaimed, "Rusty, you’re bleeding like a stuck pig!"

Still dazed, Cavanaugh looked down and noticed that he had been hit in the shoulder as well. He later surmised that the same enemy soldier had hit his radio operator, his executive officer and himself.

"That machine gunner had earned his pay," Rusty noted. "I looked up and could actually see the incoming rounds. I shouldn’t have been doing what I was doing (fighting at the front), but I was there, and the counterattack was strong, and every available rifle was needed."

Slamming his aerated helmet back on his goose-egged head, Cavanaugh mentally reviewed their situation. By now D Company had suffered four killed and fifteen wounded which represented twenty percent of his already understrength force. Item Company’s arrival and the promised resupply from Regiment were still hours away. While 2nd Platoon had yet to be fully engaged, the Japanese were attacking with a sufficiently large force to cause concern and in Rusty’s mind, remaining in their position now seemed untenable. D Company was down to one grenade per man and the Angels were struggling to keep their machine guns fed with ammunition stripped from the wounded and dead and once those guns stopped firing, the enemy would likely charge en masse.

Another problem arose due to the smoke that PFC Dubes mentioned earlier (which was possibly started by SGT Sorenson’s phosphorous grenades). Since I Company’s position was unknown, the artillery officer could no longer call in fire missions without imperiling an entire company. CPT Cavanaugh was also aware that as he and Grandpa discussed, it would soon become difficult to affect a withdrawal while under fire if he lost any additional men as it would require more Angels to carry out the wounded than might be left to cover their movement.

Rusty added, "If I had not been convinced before, I certainly was now that we were in the wrong place at the wrong time."

MAJ John M. Cook, 2nd Battalion's Executive Officer, who had accompanied D Company up the hill and observed their incredible stand against the enemy carefully made his way to Rusty's foxhole. They were both veterans of the Leyte and Manila campaigns and understood the reality of the situation. D Company was well-known throughout the regiment as proficient fighters, but even Angels have their limits.

Cook turned to CPT Cavanaugh and gave the orders that Rusty himself was considering: "Prepare to withdraw with your entire company by the same way you got up here. Commence withdrawal as soon as you are ready."

3rd Platoon’s SGT Ed Sorenson then made his way to Rusty’s (and Cook's) side and was shocked to learn that every single officer in D Company had been wounded in the firefight. After briefing receiving Sorenson's report, Cavanaugh ordered Ed to organize the company’s platoons. It was time to get off the mountain.

Retrograde Maneuver

Rusty's plan was to send 1st Platoon 50 yards down the hill to the rear to form a skirmish line. 2nd Platoon would then pass through their ranks to form another line 50 yards further down the hill. Once this was accomplished, 3rd Platoon would disengage from the enemy and move down the hill another 50 yards. Cavanaugh then ordered SGT Sorenson, who would travel with 3rd Platoon, to check each platoon he passed and do a head count. No one would be left behind and CPT Cavanaugh would be the last man off the hill.

"There was a notable interest by all concerned in complying with these orders," Rusty noted dryly.

As enemy fire increased, 1st and 2nd Platoons withdrew to their new positions down the hill, and 3rd Platoon amplified their rate of fire as they observed Japan’s troops slipping into 1st Platoon’s now vacant positions. MAJ John Cook was about to blow up their deserted 60mm mortar tube with a grenade when a mortarman rushed back up the hill to grab it. The trooper had been helping a wounded soldier off the hill then came back for his tube.

CPT Cavanaugh watched 3rd Platoon begin their own withdrawal then used his rifle to place several rounds into the wounded PFC Lipanovich’s SCR-300 radio. Making sure his casualties had all been evacuated, Rusty took off in a zig-zag line to safety as bullets snapped past.

Just behind the ridge’s crest, Cavanaugh directed positioning of the last Angels off the hill. While Rusty planned to be the last man off the mountain, one trooper remained forgotten on the ridge. PFC “Chuck” Hudson (picture to the right) still lay in the trench where medic PFC Al Haar had placed him and though under the effects of morphine, Chuck recognized that the firefight was beginning to die down.

Just behind the ridge’s crest, Cavanaugh directed positioning of the last Angels off the hill. While Rusty planned to be the last man off the mountain, one trooper remained forgotten on the ridge. PFC “Chuck” Hudson (picture to the right) still lay in the trench where medic PFC Al Haar had placed him and though under the effects of morphine, Chuck recognized that the firefight was beginning to die down.

Is D Company leaving without me? he thought with worry.

Chuck’s 2nd Platoon had moved 100 yards down the hillside before the mistake was realized. Without hesitation, seventeen-year-old PFC Billy Pettit and PFC LeRoy “Ritchie” Richardson rushed back up the slope, passing 1st Platoon coming down. Dodging several enemy squads while partially concealed by the smoke, after a nerve-wracking search, Billy and LeRoy found their wounded buddy and half dragged, half carried Chuck down to 2nd Platoon which was waiting in a ravine with great anxiety.

"I don’t know how any of the three of us were able to survive," Billy told me decades later. "It was a miracle no one was killed."

"I was lifted out of the area and do not remember a thing until I saw LeRoy ‘Richie’ Richardson and Billy Pettit," Chuck noted. In true Angel fashion, he promised his rescuers a case of beer. Upon reaching 2nd Platoon, PFCs Joseph "Joe" R. Miller and Alex "Big Chief" Village Center joined the effort to carry Chuck.

"They lifted me onto the poncho and bounced me down the mountain to safety," Hudson recalled decades later with deep emotion. "How do you thank someone for 63 years of life?"

Meanwhile, when SGT Ed Sorenson did his roll call, he came up short and told SGT Royalle A. Streck to join him on their own courageous trip back up the hill. The two sergeants made their way through the smoke until they found themselves within 3rd Platoons’ former positions on the hilltop. When no one responded to their shouts, they surmised they must have missed counting an evacuated casualty. Ed and Roy then looked up in alarm to see enemy officers in white uniforms moving to flank them.

"We executed the maneuver known as, 'Get the Hell out of here,'" Ed laughed.

Safety & Brown Creek Bridge

No one knows why the Japanese on Mt. Bijang failed to follow D Company across the crest and down the slope where they could have inflicted even more casualties. D Company, with its 24 wounded and 4 dead, continued their slow leapfrogging down the hill until they were about six hundred yards from the Brown Creek bridge where they could see ambulances and trucks gathered. They also finally saw the MIA I Company, and the battle-worn D Company paratroopers shouted angrily at their comrades. Many in D Company believed that I Company "had pulled out on us!", when in reality CPT Robert Kliewer had been unable to push I Company through the Japanese lines and had done his best to rush down the hill and around to the southern slopes to D Company's hilltop positions.

No one knows why the Japanese on Mt. Bijang failed to follow D Company across the crest and down the slope where they could have inflicted even more casualties. D Company, with its 24 wounded and 4 dead, continued their slow leapfrogging down the hill until they were about six hundred yards from the Brown Creek bridge where they could see ambulances and trucks gathered. They also finally saw the MIA I Company, and the battle-worn D Company paratroopers shouted angrily at their comrades. Many in D Company believed that I Company "had pulled out on us!", when in reality CPT Robert Kliewer had been unable to push I Company through the Japanese lines and had done his best to rush down the hill and around to the southern slopes to D Company's hilltop positions.

Bleeding from his head and shoulder, CPT Cavanaugh met up with CPT Kliewer and together the two, along with MAJ John R. Cook, reported to COL Edward H. Lahti who had personally led the resupply party to the bridge from Sugar Central. Rusty and Bob gave brief reports to "Bid Ed" and MAJ Cook noted that there were confirmed 75 enemy dead on the hilltop. COL Lahti and MAJ both agreed with Cook's later case study of the Mt. Bijang battle: CPT Cavanaugh's "actions and bearing were such as to inspire confidence in his men and promote esprit de corps in his unit."

CPT Cavanaugh, however, wrestled with his own feelings on the engagement. He noted, "I had a feeling of real relief that we had avoided being overrun and sustained a more serious loss of life, but also a feeling of having failed to accomplish our mission."

COL Lahti, however, felt that Rusty had made the right call. D Company had nearly been overwhelmed by the enemy's superior numbers and I Company's inability to join in the hilltop fight as had been planned.

"I felt a great feeling of respect for Colonel Lahti who never questioned my decision," Rusty said years later. "The Company had fought well and there were many heroic acts by many D Company men that day, acts that have never been and will never be fully recognized."

Although he could have been evacuated in an ambulance, Rusty elected to stay with his men and rode with them in the lead truck back to Sugar Central. Arriving around 1800, he reported again to COL Lahti and more than a few Angels stared at Cavanaugh’s helmet with its two freshly punched holes. Big Ed listened quietly as Rusty and CPT Kliewer of I Company recounted their engagements in further detail while medical staff saw to their wounded.

After Lahti dismissed his company commanders, Cavanaugh went to look after his wounded and noted, "The Regimental Aid Station was a busy place when I arrived. There were many with far more serious wounds than my own, so I sat on a stool awaiting..."

After making sure his fourteen wounded men received the attention they needed, Rusty yielded to the surgical staff who initially believed his injuries were severe enough to keep him out of action for awhile. But Cavanaugh had other plans and was soon back at work.

"When the doctor finally treated me," Cavanaugh recalled. "He found that I had two wounds in my shoulder. A grazing wound from a bullet and a puncture wound from which he dug out a small fragment of metal. To this day I’m not sure whether it was a mortar fragment or a small piece from my helmet… The knot on my head was not deemed serious and I left the aid station with my arm in a sling and ready for some rest."

The next day, March 14 (X+42), CPT Cavanaugh went back to check on his wounded men and stopped to visit with his good friend, my grandpa, 1LT Carrico, who awaited medical evacuation and most likely a medical discharge after more than four years in the service. The doctors told Andy that he would live, but that he would struggle with arthritis in later years.

"They were right!" my then-ninety-six-year-old grandpa laughed.

Cavanaugh noted that his XO’s "wounds were quite serious. However, he was anything but depressed and was relieved to be going home." It would be the last time the two friends saw each other until many years after the war. Andy explained that he was flown in a piper cub to the forward hospital at Bilibid Prison where the last of the rescued Los Baños internees were preparing for their trips home.

"I fretted over my comrades left behind," Grandpa remarked. "Needless to say, news from the front was sketchy at best, and of course, no mention was made of the actual battles going on, but I could visualize the hardships they must be going through." It was the love of an Angel for his brothers still fighting in Hell.

And while the official rosters note Grandpa as being "slightly wounded", medic PFC Al Haar, who cared for all the casualties on Mt. Bijang, later noted with some humor, "Andy would probably disagree with this as he spent nine months in the hospital recovering..."

Aftermath

On March 19 (X+47), 1945, six days after D Company’s ordeal on Mt. Bijang, COL Lahti ordered a combined I and F Company patrol to reconnoiter the mountaintop to assess the remaining enemy positions. Joined by Filipino guerillas, the patrol estimated that D Company, with its 95 men, had encountered an enemy position readied for 300 troops with 15 machine gun emplacements and six mortar dugouts. The Japanese lines were laced with interconnecting trenches, fortifications and tunnels and the Angels’ patrol estimated that the positions could have held off a reinforced battalion. Everyone considered D Company lucky to have survived.

Of the hilltop fight, Cpt. Cavanaugh wrote, "(It) stands out as a day which was the most emotional, demanding, and frustrating of my thirty years in the Army… I have often wondered what the outcome…would have been if I had elected to remain in our positions an hour or so longer."

Of the hilltop fight, Cpt. Cavanaugh wrote, "(It) stands out as a day which was the most emotional, demanding, and frustrating of my thirty years in the Army… I have often wondered what the outcome…would have been if I had elected to remain in our positions an hour or so longer."

Rusty added proudly, "(D Company’s) actions…in the assault of Bijang will always remain in my mind as an example of the great soldiers we had in the 511th. There were many heroic acts by many members of the company, and I wish I could give credit to all of them. It suffices to say that the whole company put up a magnificent fight…"

2nd Battalion’s Executive Officer Maj. John H. Cook added, "The training of the men and officers in Company D was a tribute to all echelons of the entire regiment and particularly to the company officers and noncommissioned officers. Officers were quick to correct mistakes made by their men, and were alert, showed great personal courage, and each by his own example inspired the men under his command. Each order was given within the writer's (Cook's) hearing was quickly and efficiently complied with to the best ability of the recipient."

No wonder General Walter Krueger called D Company and the 511th Parachute Infantry Unit, "the God-damned fightingest outfit I have ever seen!"

If you would like to learn more about the history of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of the book WHEN ANGEL'S FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II, available in the regimental online store, on Amazon or wherever military history books are sold.

D Company's Partial Casualty List for the Battle for Mt. Bijang - March 13, 1945

| LAST NAME | FIRST NAME | RANK | STATUS |

|

| ALLEN | ROBERT P. | Pvt | KIA | |

| ARROWOOD | RUFUS D. | Pvt | SWA | |

| BRADY | JOHN J. | S/Sgt | WIA | |

| CAVANAUGH | STEVEN E. | Capt | WIA | |

| CARRICO | ANDREW | 1st Lt | LWA | |

| CEGIACNIK | RAYMOND | Pvt | KIA | |

| LIPANDVICH | ROY C. | Pfc | LWA | |

| LONG | RUSSELL W. | Pfc | LWA | |

| McGeath | HAROLD C. | Pvt | KIA | |

| McGLEN | TOMMY J. | Pfc | LWA | |

| MURRAY | PETER J. | Pvt | LWA | |

| NORTH | EDWARD H. | Pvt | LWA | |

| OSMIN | JAMES W. | 2nd Lt | LWA | |

| RICHARDSON | EARL D. | Pfc | LWA | |

| STEVENSON | STUART D | Pvt | LWA | |

| VAUGHN | DAVID V. | Pfc | LWA | |

| WILCOX | WILBUR L. | S/Sgt | LWA | |

| WILKINSON | WILLIAM | Pfc | LWA | |

| ZARR | GEORGE | Pfc | LWA |

To learn more about the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of our books on the Angels: