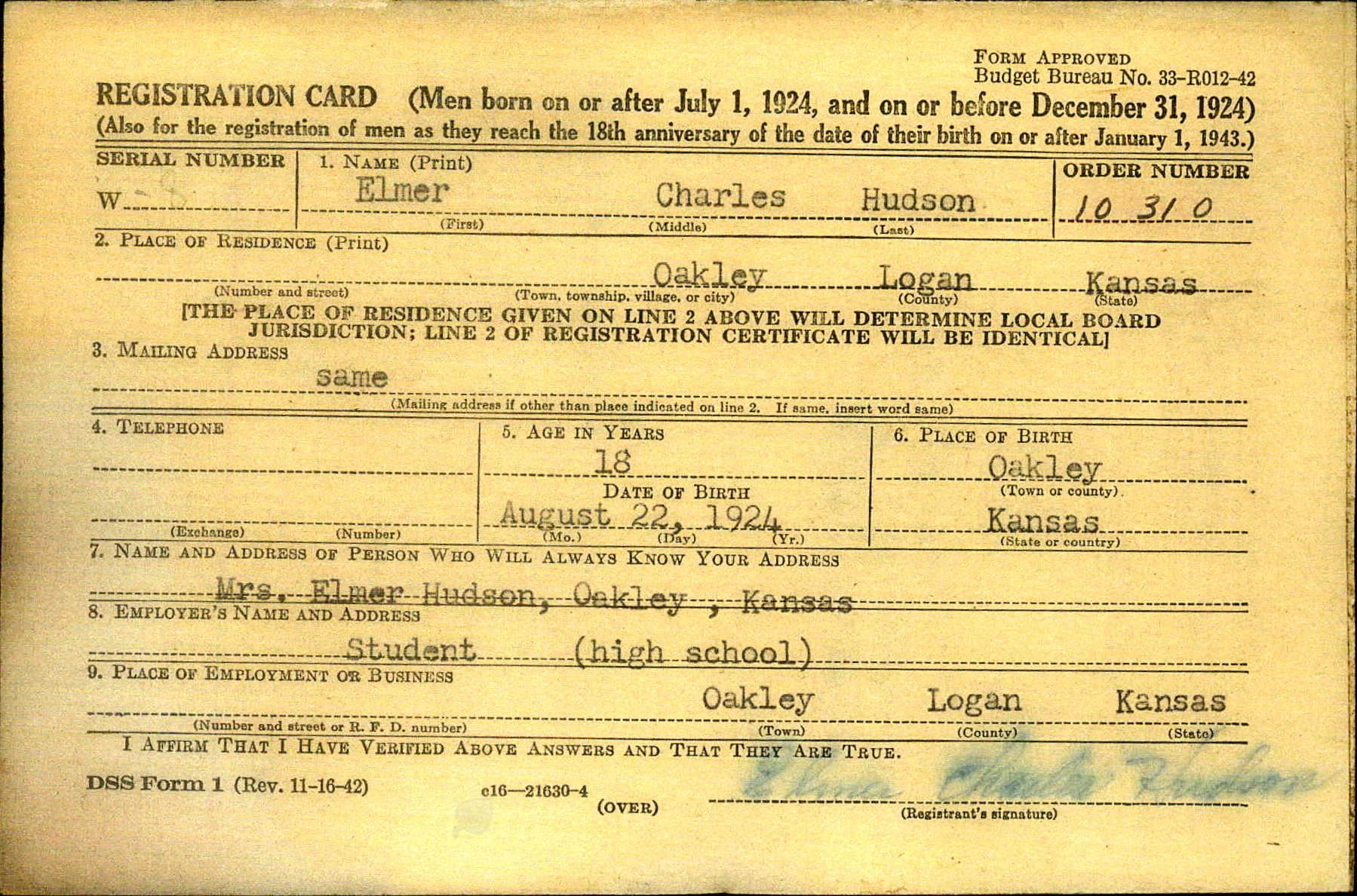

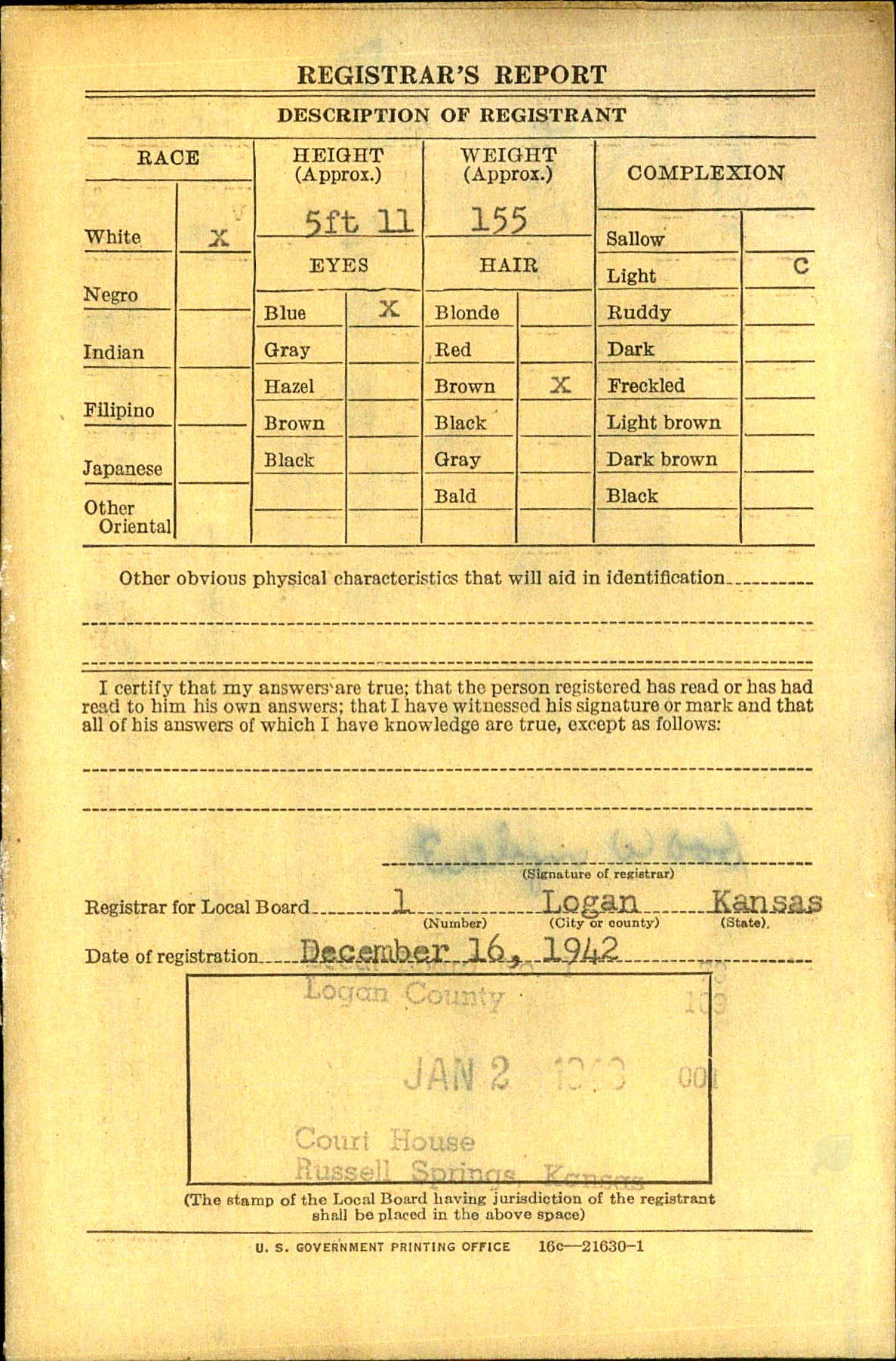

Pfc. Hudson, Elmer C.

Company D, 2nd Platoon Mortar Squad, 511th PIR

August 22, 1924 - September 11, 2009 (Age 85)

Citations: Purple Heart (OLC), Presidential Unit Citation, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Philippine Liberation Medal with service star, the American Defense Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three Battle Stars and one Arrowhead

Unit Nickname: "Chuck"

Chuck was born on August 22, 1924 in Oakley, Kansas to loving parents, Elmer Clarence and Christina Shafer Hudson.

Chuck was born on August 22, 1924 in Oakley, Kansas to loving parents, Elmer Clarence and Christina Shafer Hudson.

After 14 weeks of Basic Training at Camp Roberts, Ca., I was asked to join the 11th Airborne to become a paratrooper. I was sent to Fort Benning, Ga., where I took more training, culminating with 5 jumps from a C-47. After completion of our jump training, we were sent to Camp McKall, N.C. where I joined D Company of the 511th Airborne Division.

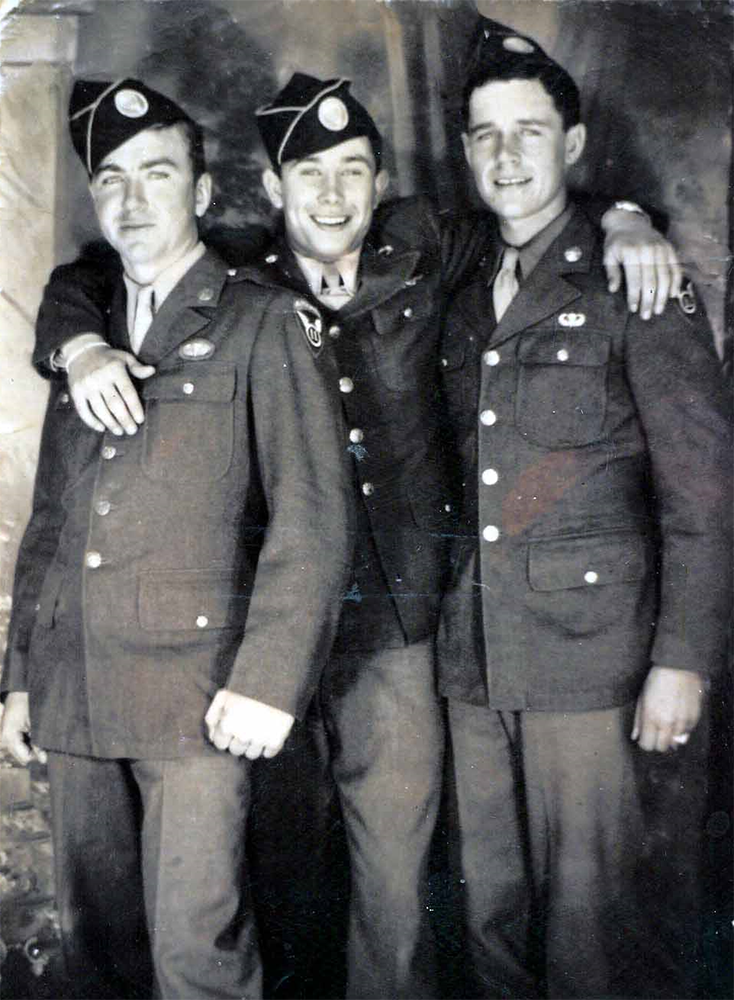

Photo at right: Pfc. James Kennedy, Pfc. Joseph "Joe" Miller and Pfc. Elmer Hudson with new Jump Wings. Taken at Camp Polk, LA. Photo courtesy of Jane Carrico.

Following that assignment, the Division was sent to Camp Polk, La. Camp Polk was all mud! (We didn’t know at the time, but we were being trained for the mud in Leyte in the Philippines). We left Camp Polk for a two-week leave to go to our homes; the only leave I was to get for the next 2 ½ years while I was in the service.

After our return from leave, we were transferred to Camp Stoneman in California. While there, we were trained in house-to-house battle techniques. On May 3, 1944, we sailed from San Francisco Bay into the Pacific Ocean, for a 24 day journey on the “Sea Pike”, which took us down the coast of South America, over to Australia, finally reaching New Guinea.

Two days out of New Guinea we were greeted by “Tokyo Rose” who had a radio station that could reach us on the Sea Pike. She said: “Welcome, 11th Airborne. We now where you are; you will never make it to New Guinea.” This sent chills up my spine! Of course we did land in New Guinea on May 27, 1944, and eventually ended up in Japan!

After more training in New Guinea, we were taken by APA Navy ship to Leyte, Philippines on November 18, 1944, where we were immediately put to work unloading LST’s. The shells that we unloaded were 155 and 105mms. (These could have been the same shells that struck the 2nd Battalion column when Col Shipley lost a foot and Capt Jenkins was killed.) After the completion of that unloading task, we prepared to go into the mountains of Leyte where our assignment was to take out a Japanese supply trail, which ran from one coast to the other. Before leaving the beach of Leyte, we all stacked our duffle bags on the sand there, and laid upon them, looking out towards the Pacific The last of the battle of Leyte Gulf was still going on and the Gulf was full of Navy ships which were being attacked by the Japanese Zeros and bombers, filling the sky with flack. One Jap bomber flew over and dropped its bombs and out of nowhere came this P-38 Navy fighter; one burst of gunfire and the Jap bomber went down. It was like being in a movie with a front row seat! As we moved out, the P-38 bomber waved to us as it flew by the shore. Leyte was 30 miles wide, and it took 30 days to take it. We made about a mile a day – one half mile down and one half mile up to the high ground where we stopped at night. It rained every day and every night: Rain and Mud and Mud and Rain!

We had a Philippine guide with us. We asked him: “How far to Ormoc?” He replied “Just one more mountain”. On December 25, 1944, Christmas Day, we came out of the jungle at Ormoc.

We were given our duffle bags back, and given two weeks to get things back together. Then off to another Island called Mindoro. At Mindoro, we were told that we would be jumping at Tayaytay Ridge, which was 30 miles from Manila. On Feb 3, 1945, in preparation for the assault on Manila from the South, we spent the night before the jump under the wings of our planes. At daybreak we loaded into the planes and started the flight to Luzon. I had no problem with the jump; I landed in a cornfield. As I was removing my chute I saw a man approaching me. I raised my grease gun and pointed it towards him: I could not figure out if he was Chinese or Japanese. The man said: “Don’t shoot, me, Chinese”. What he did not know was that I had pressed my clip release and I could have shot him if I had wanted to.

We were given our duffle bags back, and given two weeks to get things back together. Then off to another Island called Mindoro. At Mindoro, we were told that we would be jumping at Tayaytay Ridge, which was 30 miles from Manila. On Feb 3, 1945, in preparation for the assault on Manila from the South, we spent the night before the jump under the wings of our planes. At daybreak we loaded into the planes and started the flight to Luzon. I had no problem with the jump; I landed in a cornfield. As I was removing my chute I saw a man approaching me. I raised my grease gun and pointed it towards him: I could not figure out if he was Chinese or Japanese. The man said: “Don’t shoot, me, Chinese”. What he did not know was that I had pressed my clip release and I could have shot him if I had wanted to.

Well, on to Manila: D Company spearheaded the attack on Manila. Our first stop was Imus Cavite. The Japanese were caught with their pants down, they did not know we were in town. As we traveled down the road into Imus, we were met by hundreds of Philippine civilians who greeted us with open arms. As we approached Imus Cavite we encountered a stone wall about four feet high, surrounding a large courtyard. We set up our machine guns, mortars and rifles, on the walk and began our attack. The Japs were by then running for cover in the large barracks-like building. At this point, things got worse for us. Men were killed in front of the two large doors at the entrance; Sgt. Tashler, a squad leader in the 2nd Platoon, was one of those killed. Schaffer and I were behind the stone wall when Tashler was killed. We saw him walk in front of that door as if he didn’t know the Japs were firing out that door. Another trooper was hit on our right. We saw another trooper go over to help him and he also was hit.

Sgt. Steele played a heroic part during the battle for Imus. He was killed three days later in the battle for Manila. The 2nd Platoon was left to protect the bridge at Imus Cavite. The next day we all entered Manila from the South.

The battle for Manila was filled with action; firing down the streets, and house to house fighting. While this was happening, the Japs were burning Manila to the ground. I have read since then that about Manila; the Japanese killed 100,000 Philippines during these days. By the way, D Company was selected to lead the assault on Manila by Col Holcomb. As we entered Manila from the South, we met the First Calvary (I believe) coming in from the North. Our Company turned right towards Fort McKinley. By this time we had a large assault force plus tanks for support. There was a large open plain looking towards Fort McKinley and Nichol’s Field. We started across following the tanks that were firing at Japanese trenches just this side of the Fort. I saw bodies tossed in the air from the shellfire. Suddenly the firing stopped and so did D Company D. We were left there overnight and told to shoot anyone coming out of the Fort. We did.

The rest of 511th entered the area and with the help of the Navy Air Force we took the Air Field area. By this time, I was beginning to think that I was invincible. We had been in a combat area for months: Leyte, Luzon, Imus Cavite, Manila, Fort McKinley, Nichols Field. And now D Company will take a mountain called Mt. Bijiang!

Mt Bijiang: The Last Mountain - or - Die Another Day

We had seen mountains before in Leyte, but this mountain would be my last one with Company D. Mt. Bijiang was our next battle with the Japs and my last day with Co. D. The date was March 13, 1945. I don’t know if it was Friday or not, but I stay away from the date of the 13th ever afterwards!

We had just gotten 22 replacement troopers due to our losses in the fighting in Imus Cavite, Manila and Fort McKinley. We lost those men after our jump into enemy territory at Tagaytay Ridge. We fired on the mountain with heavy shells for hours, I believe, before starting our climb upwards. Shells were still coming in when we got to the foot of the Mountain. I remember the shelling was so close that shrapnel was raining down on our steel helmets. After the shelling stopped, we moved forward up the Mountain. As I recall, the 2nd Platoon was in the middle as we started up. The 1st Platoon was on the left and the 3rd Platoon on the right.

I heard a burst of machine gun from the far left. I looked in that direction and saw a soldier fall. I hit the ground behind a hole. From then on there was fierce fighting all the way to the top of Mt. Bijiang for what seemed like hours. After reaching the top of Mt. Bijiang we relaxed a bit as we thought the fighting was over. That was not the case! The next thing we knew all hell broke loose; the Japanese had moved back and set up mortars.

Being a mortar gunner, I knew that the Japanese had zeroed in on us. One shell fell to the right of me and then another shell to the left. The next shell was coming down the middle. I could see several shells in the air coming right down my throat! I protected my face with my right arm in front, and caught five pieces of shrapnel in the arm, saving a hit to my head. This shell moved me back about 20 feet.

I heard a solder to my right yell: “I have a man killed over here!”. I never did pass out, nor did I have any pain from the hit for about 10 minutes. Al Harr, our Medic, got to me and gave me a shot of morphine, and took care of me like a professional. He laid me down behind a hole and asked for my rifle, but I told him: “I want to keep my rifle”. He didn’t press the matter. I was aware that there were killed and wounded soldiers all around the area. By this time, the Japs had counter attacked and were moving in on us. I found out later that 19 soldiers were wounded or killed in this battle.. It was a bad situation. Two of the wounded were our officers, Captain Cavanaugh and Lt. Carrico.

By this time we were running out of ammunition. Seems like we were always running out of something – food or ammo. I believe it was I Company who were supposed to bring us ammo. We had to give up on Mr. Bijang because of these problems.

At this point, I was lifted out of the area and do not remember a thing until I saw LeRoy “Richie” Richardson and Billy Pettit. They had a poncho by each end. They lifted me onto the poncho and bounced me down the Mountain to safety.

There is one note I would like to enter here to the story that Billy Pettit wrote in his story about this day on Mt. Bijiang– which was very well put. As Billy Pettit stated:

“Mistakes are sometimes made in the heat of battle. Some can be corrected while time cannot heal others. In the case of PFC Elmer Hudson on Mt. Bijiang, timely action to correct an error saved his life. Mortar shell fragments had seriously wounded him in his arm and both legs. After rendering first aid, he was placed in a slit trench to await evacuation. As the Japanese counter attack became more intense, the order to withdraw was received. Hudson’s platoon had withdrawn about 100 yards down the hillside when someone mentioned Hudson. Realizing he was still on the Hill, the Platoon stopped while two troopers raced up the hill, pulled him from the trench and dragged him downhill where an anxious platoon and a makeshift stretcher awaited him. He was released from the hospital and discharged from the Service almost a year later.”

The thing that Billy did not mention was those troopers were himself and LeRoy Richardson. After we came to the bottom of the hill, I was carried by others; Joe Miller and Alex Villagecenter are among the names I can remember.

Thank you, Company D and the leaders of Company D for getting us off of that hill.

Thank you, Billy Pettit and Thank You, LeRoy Richardson, who is no longer with us for coming back up that hill 100 yards through enemy fire. How do you thank someone for 63 years of life?

Thank you, Billy Pettit and Thank You, LeRoy Richardson, who is no longer with us for coming back up that hill 100 yards through enemy fire. How do you thank someone for 63 years of life?

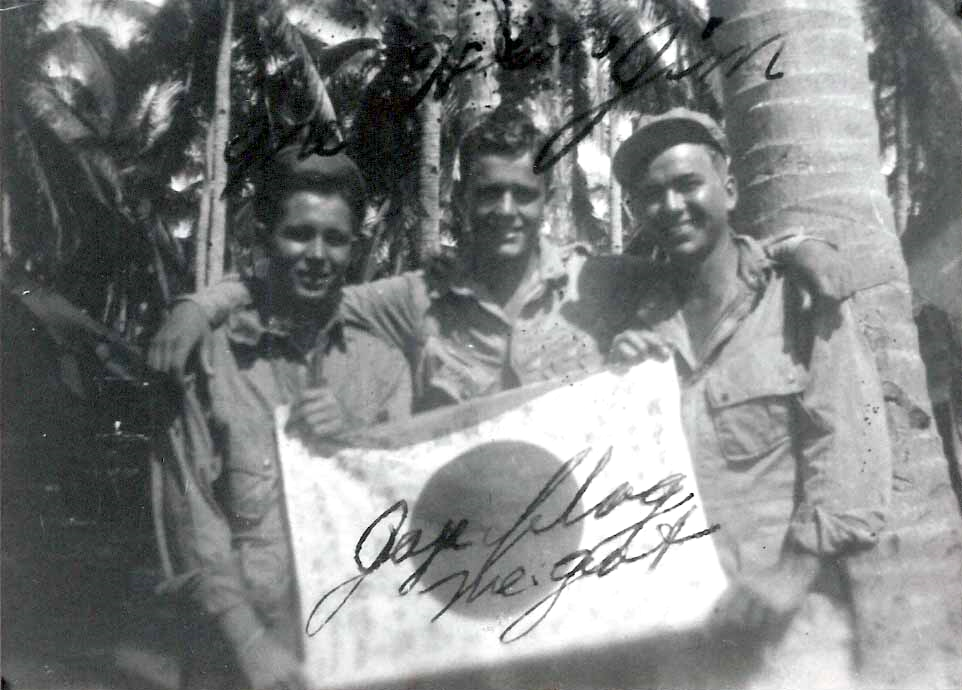

Photo at Right: The 3 troopers who took Camp Polk photo above. Left to right: Pfc. Elmer Hudson, Pfc. Joseph "Joe" Miller and Pfc. James Kennedy

I was taken back to the Sugar Mill where we had started from that morning. Doctors were waiting for us, and that night they took 127 pieces of shrapnel out of my legs and right arm. The next morning I was taken to Manila in a LS piper cub to the hospital set up in the Bilibid prison. I woke up the next day with three casts; both legs and my right arm. The Doctors must have thought that I had broken bones. They Bi-valved the right leg so it could be dressed. I was put on a Hospital Ship “The HOPE” going to Hollandia, New Guinea. The trip took 7 days. When we arrived there, I had gangrene in the right leg and it was swollen to twice the size it should have been, and was full of maggots. I was taken from the ship and up the red clay hill to a field hospital in Hollandia. There two doctors examined me – one was an old Major and a Captain Ritter. The Major wanted to remove my leg, and at the time I really did not care what they did. The doctors were talking in my presence about my leg as if it was a stick or some other thing. Capt Ritter made a suggestion that the leg be split in eight different places, about a foot long on each split, and drain it. This procedure was done and it took 8 months to heal, but they saved the leg, which was ok with me. After about a month there, I was given some money one day, and told that I was going back to the United States. I was happy about this, but I still had to ask, “What Ship?” “The Hope”, I was told. (The same hospital ship that I had gotten the gangrene on. Someone must have heard about my problems on the trip from Manila, because I had the service of two nurses back to Long Beach, California.) We arrived in Long Beach May 30, 1945, 2 ½ months after I was wounded. From Long Beach I was taken to San Francisco, and then to a Veterans Hospital in Walla Walla, Washington, where I spent the next six months recovering. I left the hospital on crutches. I received travel pay to return home, but I had to use it for expenses. So I stood at the front gate of the hospital and found a ride to Denver Colorado, which was 250 miles from my home in Oakley, Kansas. I was there when the war ended.

I took advantage of the GI Bill and went to school for aircraft and industrial instruments, also was I the hotel and restaurant business for 50 years plus sales.

I married my wife Jennie Mae 45 years ago and adopted her 7 year old daughter, Denise. Jennie and I also have a son, Bradly.

Jennie and I love attending the World War II Reunions when we can, an talk to the leaders and old troopers of D Company who made the right decision to get off of Mt. Bijang when we did.

Typed by Jane Carrico.

Published WINDS ALOFT Issue 87, Spring 2009

Elmer was known as “Bapa” by his eight grandchildren and maintained his sense of humor until his death on September 11, 2009. He would often say with a smile to departing guests, “Glad you got to see me.”

Chuck was preceded in death by his adopted daughter Deedee; his brothers, Jesse and Leo; and sister Alberta.

He was survived by his dear wife Jennie; son Bradley; eight grandchildren; three great-grandchildren; his sisters, Lavaughn Durkin and Roberta Anderson; and numerous nieces and nephews.

|

|

|

2nd Platoon, D Company, 511 PIR on New Guinea. Pfc. Hudson is 2nd from the left on the front row (without helmet) (Photo by Jane Carrico) |

Elmer Hudson and his wife Jennie at Regimental Reunion (photo by Jane Carrico) |

|

|

If you would like to learn more about Elmer's exploits within and the history of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of the book WHEN ANGEL'S FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II, available in the regimental online store, on Amazon or wherever military history books are sold.