Cpl. Hale, Murray Marshall

Company D, 511th PIR

February 27, 1919 - August 28, 2015 (Age 95)

Citations: Purple Heart (OLC), Presidential Unit Citation, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Philippine Liberation Medal with service star, the American Defense Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three Battle Stars and one Arrowhead

I was born on February 27, 1919 in Peoria, Illinois, and spent most of my youthful years in the Chicago area; Evanston, to be exact. In 1937 the family moved to the Twin City Area, in the state of Minnesota, where I went to work for a small marketing company in the oil business

I was married in 1940 and in 1941 the first of our two sons was born. The second was born in 1942.

On that infamous Sunday, December 7, 1941, I was working in my service station in St. Paul, when the Japs hit Pearl Harbor. Like every other red-blooded American, I was seething with anger but there wasn’t much I could do about it. I wanted to get back at them, but that had to be some time in the future. In December of 1942 I advised my Draft Board that I was ready to go and on January 2, 1943, I raised my right hand and accepted my new job as Private in the US Army at Ft Snelling, Minnesota.

During the initial processing, the challenge was made to one and all that the Parachute Troops were seeking volunteers. The inducement of the $50.00 in jump pay did not seem to go over too big. Three of us volunteered and were accepted and three days later we were shipped out to Toccoa, Georgia. A two-day train ride got us to Atlanta, where we changed trains and were joined by several more volunteers, and headed north to Toccoa. Upon our arrival, we were greeted by a short, husky Second Lieutenant clad in spotless and razor sharp pressed officer greens, leather jacket, overseas cap with parachute patch jauntily tilted over his right eyebrow. But what really got our attention were his mirror-like polished jump boots! Could I dare to dream? He brought us back to reality by barking us to attention and instructed us to grab our duffle bags and load into a 6 x 6 truck for our ride into camp. I have not seen too many Army installations located in areas that could be described as pretty, especially in North Georgia. The terrain was quite hilly and the composite of the ground was clay and a strange shade of red, at that. At least it wasn’t snowing! I might be all right after all. We found out! We were assigned to small barracks with bunk beds, accommodating, as I recall, around twenty men. We were under the command of a corporal who was an acting Sgt of the 511th cadre out of the 505 Parachute Infantry Regiment from Ft Benning, Georgia. We of course addressed him as Sergeant. His name was R. R. Kennedy, and he informed us that the first thing after chow the next morning, we were to meet the Battalion Commander, then Maj. Norman Shipley, to see if we passed his personal interrogation as being qualified to soldier in his Battalion.

Kennedy also informed us that only about thirty percent of the volunteers are accepted. Their pre-planned physiology really worked, as it heightened our desire to become a trooper in the 511th –- So much so that I didn’t sleep too well, and included in my prayers that I be accepted. The next morning, we returned to our hut after chow, and Sgt. Kennedy ordered us to undress completely down to our underwear and shoes. We put on our OD overcoats, and we were then ready to meet the Battalion Commander. He assembled all twenty of us and marched us over to a large building where the interview would take place. When called, we were instructed to enter the room, salute the Major at attention, and report, giving our name, rank and serial number. The Major would take care of the rest. When my turn came, I entered the room. The Major and two lieutenants were seated at a long table, with the Major in the middle. I saluted smartly, and I was instructed to place my overcoat on a chair and return to stand at attention. The Major’s eyes bore right through me and in his authoritative voice he asked “Soldier, why did you volunteer for the Parachute Troops?” With no hesitation, I stated in as strong a voice as I could muster: “I volunteered for induction into the Army with the sole purpose of getting into the Parachute Troops. I knew they needed good men, so here I am.” He continued his visual inspection and inquired sharply, “What is the most you have ever weighed, soldier?” I replied “134 pounds, Sir,” which was my current weight. I was fairly well proportioned, even though I was light. I was in fairly good shape, as my work had kept me physically active. Immediately after my answer, he shot out at me: “How much is eight times eight, soldier?” and I shot right back “64, Sir”. Without another word he dismissed me. I put my coat back on, saluted smartly, did my about-face and left the room. I wondered to myself if he could hear my heart beat. I waited in the outer room till all the men had finished their interviews. When completed, Sgt Kennedy marched us back to our hut. We dressed and began to sweat it out. “Did we make it?” After a few minutes a Staff Sgt came down with the list and announced the following men were accepted as recruits for the 511th. The list included ten men – exactly half of the volunteers in our group. I breathed a sigh of relief as I was included.

We had all crossed the first line of our great expectations. We were ordered to gather our gear, and Sgt. Kenney marched us over to the D Company area. We were assigned to quarters according to Platoons. We were all assigned to Staff Sgt Al Barreiro’s Third Platoon. We were advised that our stay in Toccoa would be brief, and as soon as our Second Battalion was filled we would move by train to Camp Mackall, North Carolina, a new facility on the vast Ft. Bragg reservation, to be devoted to the training of airborne troops, exclusively. During the remaining days we spent in Toccoa, we were tested both physically and mentally. Those were tough days, built around running up Mt. Curahee, a distance of three miles, push-ups, by what seemed the thousands in the beautiful red Georgia clay, and we were introduced to the Girand M-1 30 caliber rifle, the Infantry soldier’s main weapon. We learned its nomenclature and the manual of arms in record time and marched in review for our Regimental Commander, Col. Haugen, much to his satisfaction. The only activity that could be associated with parachute training was a mock-up tower. It was 35 to 40 feet high and constructed to resemble the fuselage of an airplane, with an open exit door. After climbing the tower, we were fitted with a parachute harness that had risers attached to a cable that ran horizontally at an angle down to the ground. It would allow us to slide down, after we jumped out of the door. The cable was attached so that when we jumped out of the door, we dropped about ten feet, slid to the ground shouting, “one thousand, two thousand, three thousand”. We were instructed as to the proper way to exit the door and given the opportunity to try it. Actually, it was quite fun but we realized that the real thing would be a little more challenging. One of the most amazing reports that I read in later life from an authoritative source was the fact that the War Department had admonished our Regimental Commander, Col Haugen to lighten up on his selection process as it was taking 12,000 men to fill out the Regiment of approximately 3,000 men. To have been one of those selected, I thought was a great compliment, and I’m sure that everybody else felt the same way. These were tough and impressionable days, and a fitting introduction to our forthcoming basic training to become troopers of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment. In early February, we departed by train from Toccoa, Georgia, for Camp Mackall, North Carolina.

We arrived at Camp Mackall on a weekend, and moved into our new barracks. We were the first troops in our area and our advanced detail had arranged supplies at Regimental Supply which we drew, and set up Army housekeeping: Bunk beds, mattresses, footlockers; the basic necessities. Responding to the barking of our non-commissioned officers, we got set up and ready to begin our training. We began our basic training in early March and it ran until late May, when we went to Jump School at Fort Benning. During this period, we were restricted to the Base. No passes until basic training was completed: One of our first real lessons in discipline. Basic training was long and tedious. But this was necessarily so. Army Regulations are designed for all intellects so there is a lot of repetition. The IQ level for our Regiment was much higher than average so our training progressed and the repetitive part of it was extremely boring. We were introduced to the range road early on. It was the main route to most of our training areas and various weapons ranges. It was all sand and all hills: There was no end as far as the eye could see. The old range road will always be remembered. The days ran together. All that changed was the subjects of our classes as well as the locations. They made sure we got our miles of marching. Most of it out range road. The officers did their best to keep the classes as interesting as possible, and I thought they did a rather good job. Sundays were a free day. We used it for writing letters, doing laundry, even a movie or a visit to the beer garden if we had any money.

During weapons orientation, it was decided that I was more qualified to fire the 60 mm mortar rather than a machine gun, so they put me in a mortar squad in the Second Platoon. This meant moving into the Second Platoon Barracks, under the command of Staff Sgt. George Sharpe. Shortly thereafter the Company Mail Orderly job opened up and Sgt Sharp, at my request, got me the job which involved a promotion to T-5, a Corporal. This meant an increase in pay of about, I believe, $25.00 a month. I sent most of this home to supplement my family’s allotment. Every little bit helps in that department. Mail Orderly’s got some privileges, which were quite nice. Mail, as you know, is an important ingredient in a soldier’s morale. As the weeks continued, they increased our physical demands. We marched further and faster and went on more runs and we were getting into top physical condition in preparation for Jump School. One of our final activities for basic training was a two-week bivouac We marched out twenty-five miles and spent two weeks living in our pup tents and running through all kinds of combat simulations. We spent the last night of our two weeks in a forced march back to camp. So far in our training, this was the toughest challenge. Under the threat of disqualification from Jump School if you fell out of the march, everybody made it! I don’t remember the exact time, but we averaged nearly five miles an hour, carrying all our field equipment, including mortars, machine guns, etc. Several of the men were suffering from dysentery, so it turned out to be quite a challenge. Col. Haugen and his staff stood at our Regimental Headquarters building, and as we passed them on our route to the barracks, he voiced his congratulations for a job well done. It almost made it worthwhile! We were ready!

Jump School consisted for four stages: A, B, C and D.

A Stage was physical hardening, completely: Nothing but physical work and running.

B Stage was the mock-up towers, tumbling, and learning to maneuver a parachute with all kinds of harness activities.

C Stage was the 250-foot towers where you made several jumps, learning how to maneuver a chute actually as the parachute carried you to the ground. We spent one night making night jumps off of these towers.

D Stage was the actual jumping where we had to qualify by making five successful jumps. During all three of these stages in jump school, we also learned to pack our own parachutes, and we spent every evening in B, C and D stage, packing our chutes. B stage was uneventful, but informative. C Stage, when we moved into the towers, proved to be something else. The ride that I got on the shock harness was quite scary. They put a parachute harness on me and I lay face down on a tumbling mat. My arms were outstretched and hands clasped together. They hauled me up the tower to any height that the Sgt instructor desired. He stopped me and then instructed me to pull the rip cord. Laying face down from a height of 200 plus feet makes the gym mat look like a postage stamp. On the Sgt’s instructions, I pulled the rip cord and dropped a distance of 20 feet and the risers on the shock harness stopped me and I bounced around a little bit; and then they lowered me to the ground. As I pulled the rip cord, I changed the handle from my right hand to my left hand and shouted the name of my home state. The Sgt took note of the fact that I was a Corporal, so he set an example. He said, “Corporal, let’s see how you like it at the top of the tower!” He took me to the top. It was quite a thrill. He was nice enough to give me two rides. We rode the parachutes from the 250-foot towers several times and as we rode it down they instructed us how to steer the parachute. We also had a couple of jumps at night. We all thought this was a lot of fun, and it seemed like everybody enjoyed it. Monday was the beginning of D stage. Our first jump! We had been folding parachutes for two weeks in evening classes in B Stage, and our assigned parachute was folded and ready to go. Monday morning after chow we were marched out of the airport and went into the hanger called the sweat box and drew our parachutes, put them on, sat down and waited for our turn to get into the plane. As we waited for our turn to get onto the airplane, several of the Sergeant instructors filed among us and inspected our parachutes to be sure that we had everything fastened properly – the reserve chute, etc, so that everything was alright. Given the approval sign and while we were waiting for our airplane, the thought crossed my mind that there were several people in our Company who had never flown in an airplane, and with today being their first flight, they were going to jump out of it, as well! I wonder how they felt. I loved to fly! I remember sitting in my mother’s lap when I was five years old, going up in an old WW I Vintage Jenny in Rock Island, Illinois. But I had never jumped before, so I had some trepidation as well, myself.

Our turn finally came. We filed out into the airplane, sat down in the bucket seats on both sides of the plane, and away we went. We reached altitude of about 1200 or 1500 feet and approached the jump field. We got the command: “Stand up and Hook up”. We had the static line clasped into our left hand, and as I tried to hook onto the anchor line I discovered that my static line was too short. So I turned around to the fellow behind me and asked him to pull a stow out of the static line so that I could reach the cable. This he did, and I was able to reach the cable and hook on to the static line. As we started to shuffle to the door, they had started to jump already and we were jumping one man at a time – the Tap Off jump. As my turn came, I turned to the door, pushed the static line fastener toward the tail of the plane, and grabbed the sides of the door. I heard the Jump Master say “Go” and I pulled with both hands and arms trying to get out the door. Something was wrong! I couldn’t get out of the plane! What was the matter with me? Of course, this was happening in the fraction of a second (it seemed like minutes) I gave a big strong pull with both hands and arms and I felt a blast of air as I slid out the door - and I seemed to wipe off the side of the plane. I saw the tail of the airplane go over the top of my head and I heard a ripple. I looked down to my left and I could see the parachute was coming out of the pack and sliding under my left arm. Strangely, I didn’t get excited. I remember them telling us that if we ever jumped out of the door with the static line under our arm, we were to just reach our arm back and up as hard as we could, and the chute should pop right open. I threw my arm back and up! Bang! I felt the opening shock and the chute opened. The ride to the ground was beautiful! And before I landed, there was a Jeep there with an officer who was monitoring the landings. The plane had radioed the ground telling them of my exit from the plane with the static line under my arm. The officer sternly inquired if I was ok, and I replied that I had realized that the static line was under my arm, and I had done what they had instructed me to do and the parachute, as he could see, successfully opened. He had me remove my coveralls and looked under my left armpit where there some scrapings or “strawberries” from the chute going under there, and it was then that I realized how much trouble I really could have been in. The officer admonished me to be a little more careful in the future, and let me go. It was then I really knew that I could have been in trouble, and I got a little weak in the knees. What really had happened was that the fellow behind me had taken too much of the static line off of the back of the chute as I went into the door and it just naturally went under my arm. The Jump Master saw it after I got into the door and tried to grab the parachute pack and hold me back and that’s why I was having trouble getting out of the door. He had tried his best to stop me, but everything turned out alright, so I guess that was that. It was just an added thrill on my first jump, and you can be sure that in the future, I would be more careful.

Over the next four days, we completed our qualifying jumps, which proved to be rather routine. But they were all thrilling, and we enjoyed them, and we knew that we were now qualified: All of my buddies of D Company. We had climbed the mountain. We were now qualified paratroopers of the United States Army! We were members of the elite. We celebrated together in Phoenix City, Alabama before leaving Fort Benning. We received our wings at a formal Regimental Review when we returned to Camp Mackall.

We were now about to enter the most important phase of our training: The Combat Phase! This group of fine young men, who were hand picked by their commanders, were both mentally smart and physically tough, fine-tuned through their basic training and physically braced that they were the toughest, smartest Regiment in the Army, and no doubt will be the most decorated. By being restricted to our base all during basic training they were like a tightly wound spring, ready to fly! Now, with their beautiful parachute wings, razor-sharp creased uniform pants, bloused in bright, shiny jump boots, overseas cap adorned with a parachute patch, jauntily tipped over one eye, they, just by their appearance, demanded respect. They were fiercely proud of their outfit and were doubly quick to prove it! I believe our officers were proud of us. Combat training was long and tough, and for some reason, D Company was hard on Company Commanders. Capt. Roth went to the Regiment, as did Capt. Faulkner. Capt Freeman went to Battalion Supply. Capt. Cavanaugh came to us in New Guinea and remained as a good, solid leader.

After Jump School, we simply shifted gears, and tried to become experts in all phases of combat. The situations we trained in and for, included, I believe everything: Squads, Platoons, Companies, Battalions, and Regiments of course. Special maneuvers got larger. Most training, as I saw it, was for officer-made operations Sergeants, which put me in Company Headquarters, working closely with the Executive Officer, keeping track of situations and conditions with maps, etc., knowing what our objectives were and trying to keep track of what we, as a Company were doing. This arrangement continued until we were about to go into the Philippines. For a good reason I am sure, our Table of Organization did away with the job of Operations Sergeant, so at that time our then Company Commander, Capt. Cavanaugh, put me in Communications where I stayed until I left the Company. I remained in Company Headquarters, taking Sergeant. Sorensen’s place as Communications Sergeant when he was assigned and transferred to the Third Platoon as Platoon Sergeant. We continued our travels on range road on a daily basis, polishing our techniques and tactics and occasionally getting in a practice parachute jump. Again, It seemed to me, this was more for the officers for communications and control. We made several parachute drops over the months: These were done on the availability of airplanes. We were soon scheduled for our first night jump, And the 457 Airborne Artillery were scheduled to go before us. The night that they were scheduled we could see and hear their flight go over our Company area. It seemed that they might be going to a jump area just northwest of the area. Soon after the flight went over, we heard several emergency sirens that seemed to be going down range road. On investigation we found that they were not too far from us, so we all went out to check on them. The pilot had lost a plane in their formation with an engine problem and when he banked out of the formation he hit the tops of the pine trees and went in. We could not get back to the crash site: They kept us away while they removed the bodies. There was some fire but they were able to control that. They lost twenty-eight men. It seemed the pilot was trying to make it to the nearby airstrip and he banked with the near engine down and when he was making his turn he went in. Why didn’t he get some altitude and let the jumpers get out? What a waste. We who were being scheduled to go soon, got concerned and talked about it, and the talk got back to Colonel Shipley, our Battalion Commander that if anything like this happened to us, our men would just bail out. Theoretically, the pilot has command of everyone in the plane and you have to have his approval to jump. Shipley came down to talk to us and told us that if any engines even skipped a beat, out we would go and he would see that all the pilots got the word. We were relieved to hear this, and our first jump went off with only one casualty. We lost a man who accidentally opened his reserve when he went out the door, and he got tangled up in it and fell to the ground.

After the successful Knollwood Maneuver in December, 1943, we coasted for a month and then got ready to go on the big maneuver at Camp Polk, Louisiana. We were to leave around January 10th, 1944. The advance detail that went to Camp Polk got in a little hot water. The first night in the PX they ran across some tankers who wore boots as part of their uniform. Not paratrooper boots – just regular boots. However, they had them bloused as a paratrooper. They were promptly challenged to un-blouse them, as they were not jumpers. After their early resistance – it took a few bloody noses and removal of the boots by cutting them off to get the point across. I don’t know if the MP’s were able to restore order. I understand it took Colonel Haugen to explain that this was a part of the tanker uniform. We left Camp Mackall around January 10th. Conditions in Camp Polk were the world’s worst. Not mud, but gumbo. It was cold and rainy, and living and fighting the elements in addition to fighting the enemy flags were terrible. The maneuver was a success. We moved out of the gumbo and back into the barracks and got ready to go overseas. Now began the rumors and speculation Everybody naturally thought we would be going to Europe. There was still hot speculation on just when we would cross the Channel and invade France. Well, whatever, we were ready. We enjoyed our stay in the deluxe barracks at Camp Polk until it was time to go.

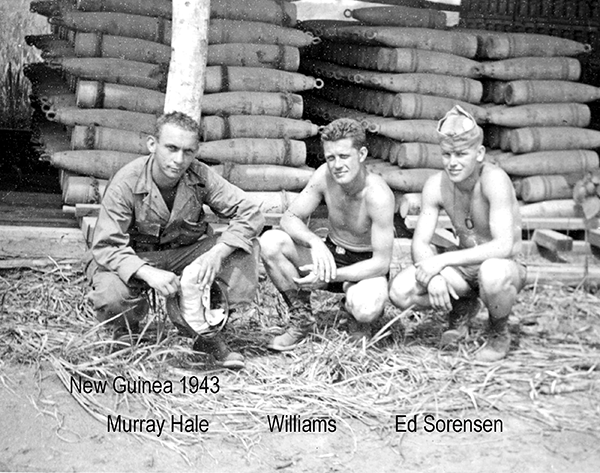

We boarded our train in Camp Polk and it didn’t take long before we realized that we were headed West. We sure were following the advice of good old Horace Greeley: “Go West, young man, go West.” We could still end up in Eurpoe, but not very likely. We could still crank out rumors pretty good, which we did, but try as we may we were unable to get any kind of confirmation from our leaders. It was a routine trip with daily stops for exercise, calisthenics, and jogging. The food was typical Army and Spartan, and not too tasteful. We saw some beautiful scenery as we passed through the mountains but it was not much appreciated, as we were NOT on a vacation. We got daily lectures on security and all of our unit identity had been stripped away. I don’t believe we were given our exact destination, but after three days we arrived on the West Coast at our Port of Embarkation: Camp Stoneman. It was located at the head of greater San Francisco Bay in the general area of Martinez. We had never heard of this base and during our many security lectures they made a great point of this fact. It was a large base, of course, and being on the morale building side, the accommodations if you can call them that, were large, clean two-story barracks with beautiful showers and mess halls full of great and wonderfully prepared food – even with extended hours. We were not used to this kind of luxury. The first order that we were given was that we were to be restricted to the base at all times. This order had a ring of challenge to it for many of Haugen’s future heroes. We quickly became aware of the Burma Road, through troops that had arrived before us. This was a trail that led off of the base that gave access to a road that eventually led to the highway to Martinez. Surprise! It was unguarded! The officers kept us occupied during the so-called duty hours with lectures, calisthenics, running and so forth. The evening hours were ours, and after a couple of days three or four of us decided to try the Burma Road. Using our well-practiced methods we moved silently out of the camp and to the highway and hitch-hiked into town. It was easy to get a ride as everyone wanted to lend the GI’s a helping hand with a boost, a salute, or to buy us a beer when available. We spent the evening browsing around the town, mostly saloon hoping. Our soldiers traveled about in small groups, which was common, and the natives were aware that Camp Stoneman was a P.O.E. They socialized and mostly they were interested in where we were from. I’m sure they knew – or thought they knew – where we were going. It was simple to keep our secret as our uniform was a simple private in our great US Army. All of our identifying jump boots, wings, Airborne patches, were safely stowed away. We had a pleasant evening in town and the time passed quickly. It got to be time to be thinking of returning to camp. Four of us, Sorenson, Zadoorian, Williams and myself started down the road and with what little traffic there was, the offering of a ride wasn’t forthcoming in response to our hitchhiking. Chic Williams said “Not to worry, Red Zadoorian and I will pick up a car.” Chic, in his earlier days had mastered the tricks of a professional car thief. I happened to come by this information from Red while we were in Camp Polk. Chic had grabbed a car in one of the nearby towns at Polk, and they had kept it hidden or I should say, concealed in the woods near camp so that they always had transportation. I don’t believe Sorensen was aware of his talents, but it wouldn’t be long before he would become aware of it.. Well, to make a long story short, we moved over into a residential area and Sorensen and I waited on the corner while Red and Chick scouted the area. The first car they chose didn’t work out. As Chick was entering the vehicle, someone came out of the house. Red was across the street, and Chick quickly waved at Red and shouted, “Bill, wait for me” and ran over to him and they walked up the block. Evidently the person coming out of the house was not aware of what was taking place, so no effort was made to follow them. In the next block, they spotted another vehicle, which they stole. They drove back and picked Sorensen and I up, and we returned to camp without further incident. We left the car in an inconspicuous spot, slipped down the Burma Road and returned to our barracks. We had accomplished a pleasant evening. Another adventure in Khaki.

The balance of our stay at Camp Stoneman was routine. We finally got the word that we were moving out. One year, approximately since we had graduated from Jump School. In early May, 1944, we loaded on a ferry boat and ferried down to the San Francisco Bay docks and loaded on our ship, the great Sea Pike. We were loaded down with our duffle bags, gas masks, steel helmets, with our D Company identification marked in chalk across the face of our helmet. We came off the ferry and trudged up the gangplank onto the Sea Pike, and filed down to our assigned area in the hole. The bunks were stacked five or six high. I looked around in the dim light in the hole. Everything was steel: Stairs, floor, walls, or bulkheads, whatever you’re supposed to call them. I really felt contained. It was not a pleasant feeling. Finally, after what seemed like several hours – our final roll call was barked out by Fillippelli, our First Sergeant. All present and accounted for and we were ready to get under way. It was May 8, 1944, we were permitted to go up topside as they left the dock, and moved down the Bay, turned West by Alcatraz, and approached the great Golden Gate Bridge. There is an old traditional belief that if you throw a quarter into the Pacific Ocean as you pass under the Golden Gate Bridge going West, you shall return safe and happy. The water was loaded with splashes! We were traveling alone – No Convoy.

The Sea Pike has to be faster than it looks. We were in the hands of the Merchant Marine, now. “Now Hear This” was barked out over the speaker system, and then followed our instructions, whatever they may be. We furnished the details for the clean sweep, fore and aft and hauled the kitchen garbage to the fantail for daily dumping. The sailors manned the water for the hosing and scrubbing down of the deck. Our meals were prepared by our own cooks, again, and we were to be fed twice a day. Most of our day was spent in the chow line or at least that’s what it seemed to be. The Ship’s crew had great food. We schemed, scraped and stole to get our hands on any of it. Sometimes we were successful. I can remember holding a man by the legs while he crawled through the mess hall porthole and stole a plateful of bread from the table. This is how desperate we were for any morsel of food. After spending our first night below in our bunks, we were able to take a blanket up topside and sleep on deck. Sleeping below was difficult: Hot, smelly snoring, engine noise – just completely unpleasant. The first morning we were at sea, our officers announced that our destination was going to be New Guinea, which of course meant that we on our way to help General MacArthur keep his pledge to return to the Philippines. When we were not in the chow line or doing exercises or orientation type meetings, we were playing cards. We played Pinochle, mostly. After the first few days, most of the cash was gone, so there were very few poker games, and all of the money was in the hands of the good poker players. Strangely, we did not discuss our destination too much. We had trained long and hard. We had believed we were going to Europe – but really, what’s the difference? We had to fight till victory, so let’s get started. I never gave too much thought to the new environment – but let me assure you – later we did! The trip was routine except for one General Quarters alarm, when three of our US Navy fighters buzzed us in the middle of the day for a routine identification check, but it is war. And it was a thrill for a few minutes. We were introduced to atabrine tablets, which were passed out in the chow line every day. This was a preventive of getting malaria and some other mosquito borne diseases that were prominent in the tropics. We had to take the atabrine every day under threat of Court Martial. They could certainly tell if you were not taking it because the atabrine caused your complexion to turn yellow. As far as we all knew, everyone took their pills faithfully.

We arrived at Milne Bay, New Guinea after about twenty-six days on the water. We stopped briefly for Orders, I presume, and then departed and steamed up the coast for a couple of days. We stopped and docked at a place called Oro Bay, which would be our new home for the next six months. D Company drew the assignment of helping to unload the ship. It took about a week. It was hard to believe that we took so much equipment to sustain a 2,000 man Regiment. Early one day in the unloading process, Bittorie ran across an interesting box that was marked for the Regimental Priest. It had markings that made one think that it might contain altar wine. John, being an enterprising young man, and thinking that some of his buddies might enjoy a little wine after a hard days work, stashed the box for later inspection. That evening, after chow and while several of us were relaxing on the deck, John brought forth the box. It was opened, with a little trepidation and wonder, and sure enough it contained six bottles of good wine. We drank it over time, and I think we each confessed to ourselves it wasn’t the right thing to do. We didn’t feel any holier, anyway.

We arrived at Milne Bay, New Guinea after about twenty-six days on the water. We stopped briefly for Orders, I presume, and then departed and steamed up the coast for a couple of days. We stopped and docked at a place called Oro Bay, which would be our new home for the next six months. D Company drew the assignment of helping to unload the ship. It took about a week. It was hard to believe that we took so much equipment to sustain a 2,000 man Regiment. Early one day in the unloading process, Bittorie ran across an interesting box that was marked for the Regimental Priest. It had markings that made one think that it might contain altar wine. John, being an enterprising young man, and thinking that some of his buddies might enjoy a little wine after a hard days work, stashed the box for later inspection. That evening, after chow and while several of us were relaxing on the deck, John brought forth the box. It was opened, with a little trepidation and wonder, and sure enough it contained six bottles of good wine. We drank it over time, and I think we each confessed to ourselves it wasn’t the right thing to do. We didn’t feel any holier, anyway.

After the unloading was completed, we moved into our Company area and built the frames for our eight-man tents. The Regimental Companies were lined up by Battalions. Each Company had a street. The mess halls were in line with the Battalions and the Headquarters, Medics and Supplies were lined up behind the Mess Halls. Everything was in order, just like a little village. The entire Division was arranged in this manner. It took a couple of weeks to get organized before our further training started. We were going to be the best trained Regiment in the Airborne.

When we arrived in New Guinea that campaign was still in progress as some of the Japanese Army was being destroyed in the Northern part of the Island of New Guinea. This meant that we kept our weapons handy at all times, with ammunition. One evening, just prior to dark, from our Company area we spotted, hanging down from the trees in the edge of the jungle, hundreds of huge bats. It didn’t take long before someone thought, “What a great opportunity for target practice”. I don’t know where the first shot came from, but I do know it didn’t take long for all of us to join in. It sounded like the war was right there! The Officers descended on the area and with the aid of the non-coms, got the shooting stopped. We succeeded in wiping out the bat population, but we also succeeded in creating a serious problem for everyone concerned. The Colonel gave the orders for our weapons to be taken away and returned to a secure area and kept under lock and key. It became a daily experience to get our weapons out and then return them and secure them again in the evening. I don’t remember when this order was relaxed, but I do remember this foolish display created big trouble for all concerned. We spent some long days in the field running through various combat problems. We went to Buna and Goona where major battles had been fought by, I believe, the 37nd Infantry Division. This was done to get us adjusted to the jungle and the climate, which was bad. The bugs were terrible and we had to dust ourselves with powder to keep the ticks away. Typhus, a serious tropical disease, was the reward for a tick bite as was dengue fever, and of course malaria. So we faithfully dusted for ticks, and took our atabrine for malaria. We turned yellow in complexion and in the eyes, but it worked!

The Australians had a good representation in the general area, and their supply depots became our favorite target. They had lots of canned fruit, turkey, canned milk, biscuits, and various other edibles. But we were partial to the fruit and milk, and especially the turkey. We made arrangements for a vehicle – preferable a weapons carrier to transport our loot. Their warehouses were guarded, but they were no match for our thieving skills. We buried our booty in our tents under the flooring so instead of a steady diet of field rations, when we were out on field problems, we had a little variety to take along. Also, we enjoyed evening snacks while playing our regular pinochle games in the evening.

Col Haugen, being a great fight fan, had instructed the Regiment to form a boxing team, which we did. We were very competitive with all other Regiments in the Division. The Engineers had built a good-sized Regimental theater in the area, and most of the fights we followed were held there. Sgt Bill Dubes was on our team and did a great job! He was a real battler – a champion in every degree. The inter-rivalry with the other units was terrific! We of course could see no one being better than the 511th! It was great for morale. We also had a football team which did very well. I believe that we were champions in that department too. But I could never imagine playing football in the tropics. Those guys were really tough and they did an outstanding job.

Jack Benny brought his USO Troop to our theater. In the afternoon, we put on an exhibition parachute jump for them. Everybody enjoyed that. It gave us an opportunity to show off a little bit. One daring trooper went out the door without hooking up his main chute, so he had to use his reserve chute. It was exciting, but I’m sure he inherited some kind of punishment. Benny’s show was terrific! Everybody went down to the theater about four hours before the show started in order to get a decent seat. We played pinochle so the long wait wasn’t too bad. Jerry Colanna and a troop of beautiful girls. What a great time we had that evening!

In spite of all the morale-building activities, after five months of New Guinea, psychologically it was difficult not to feel a little down. We thought we were fine-tuned and ready to go. What was the delay? We just didn’t know what the big picture was. We of course voiced our feelings among ourselves, and I am sure the powers that be just chuckled and thought “In due time”. One afternoon after duty hours, our 1st Sgt passed a little extra duty out to a private in our Company Headquarters. His name was Finander, and he probably earned more extra duty punishment than any two men in the 511th. There was never any excuse for the problems he created for himself. He was ordered to reshape the drainage ditch around the D Company orderly room tent. Finander refused, saying it was after duty hours. The Company Commander who was within earshot, instructed the 1st Sgt to re-issue the order. And when Finander refused again the Company Commander instructed the 1st Sgt to place him under arrest for refusing to obey a direct order. We were in a combat theater of war, and disobeying a direct order would deliver some of the most severe punishment available. It turned out to be a General Courts Martial and the verdict was fifteen years imprisonment and a dishonorable discharge. Very serious stuff and it was noted by all. Discipline at its finest and it is the final word.

November 1944 was upon us and the word at last came down that we were to prepare to move out, which made for a lot of work. It meant only one thing for us. We had to be going to the Philippines. In a matter of days everyone in every unit was brought up to strength and supply: Personnel, equipment, weapons and so forth. A convoy of US Navy ships were brought into Oro Bay and we were loaded up and we set sail to the North on November 7, 1944. After a few uneventful days, we arrived in the general area of Tacloban, Leyte, the Phillipines. The best part of the whole trip was the great food we were served by our Navy. They gave us a great steak, good food, and on the last night we were aboard, and they called it the traditional “last supper”. Combat troops embarking on a mission. It was great!

We were not committed to combat on landing. The enemy had been driven back into the mountains, and we moved ashore, set up camp and unloaded our equipment and supplies. We celebrated Thanksgiving with a water buffalo dinner and our cooks did themselves proud. We were mildly harassed by a few straggler Jap bombers dropping single bombs late in the evening, but no damage was noticed. We witnessed a few dog fights between the Jap Zeros and our P-38’s over the ocean in our area – just watching it like an air shore. Of course the enemy planes were always shot down. After a few days we were told we were moving inland to relieve the 7th Division. They were set up in a perimeter holding the Japs back in the mountains. The 7th was going to get into landing craft and make a landing on the other side of the Island at a town called Ormoc on the 7th of December. Shortly after their departure, we were given the assignment of going across the mountains to seek and destroy the enemy. After a few miles we ran out of roads, which were reduced to trails. Mud was three to four inches deep. It was the rainy season and nothing was dry. We spent the second day in a large area assembling our Battalion and getting ready to move up into the mountains in a more organized way.

D Company moved out on the point the next morning and we led the way up the hills. No sight of the enemy. In mid-afternoon, in a sky gray with foggy mist, suddenly there was a terrific roar of an airplane coming down. Everyone dove off of the road into the bush as the plane exploded into the ground. It dug a crater about ten feet deep and fifteen or so feet across. It didn’t burn and we could not tell what kind of airplane it was or who it belonged to. We found no sign of a body or parts. So it was reasonable to assume that the pilot must have bailed out. That night, we slept in a deserted native village in huts that were made from nepa palm trees. Luxury – we were covered and managed to stay dry. Reasonably dry, that is. The next day we had another airplane experience. We were getting a food supply drop from a C-47, and as the plane flew over us about 300 – 400 feet up, we could see the crew in the door with a stack of ten in one rations, ready to be dropped. They checked our identity, and instead of shoving the rations out of the door they flew on a little way and made a banking turn to go around and drop them on the way back. When the pilot banked to make his turn, he went the wrong way, and the load of boxes tipped back into the plane. The sudden shift of weight caused the pilot to lose control and he was flying so low that he never had a chance: He flew it right into the ground! We of course immediately sent a detail out to the plane to see what we could do if anything. By some miracle, the plane didn’t burn. But all but one of the crew was dead. A Sgt. crew member evidently jumped out just as the plane went in, and after falling through the trees managed to survive without too many real serious injuries. We buried the crew, after stripping their shoes, a common practice to keep them from falling into enemy hands. An expensive delivery, as the C-47 appeared to be a brand-new airplane.

We still had not run into the enemy. The next day was December 6th.. We were going to get another supply drop. In late afternoon, we were in a clearing, near the top of a hill. We could hear the plane coming over. We were, of course, alert, watching as it turned into the area. They shoved a stack of rations boxes out the door and down they came. Everyone on the trail tried to stay clear, ducking into the surrounding trees for protection. Not too far from where I ducked, there was a terrific thud and a cry, “Man Hit!”. Dick Mills, 1st Platoon, got hit in the head and never knew what hit him. Our first casualty. Killed by a ration box. The sad thing is, there proved to be several more before the war was over. That night, we watched the Navy soften up the beach at Ormac for the December 7th landing of the Division. It was like a great Fourth of July exhibition. Off in the distance, we could see the tracers hanging in the air as they fired. They hung like a red curtain in the sky. The enemy would have to be dug in pretty deep to be protected from that firing exhibition.

December 7th Our first combat Day! D Company had the assignment to take the rear and carry 81 mm mortar ammunition. A heavy addition to our already heavy muzette bags. We marched down a dry creek bed most of the morning, which was fairly slow going. Around 1:30 in the afternoon, rifle shots rang out up toward the head of the column. Headquarters Company were on the point. We stopped of course, and put out security on both flanks. The firing was sporadic but continued. Word came back for us to bring up our mortar ammo, so D Company passed through E and F Companies. We approached a large clearing, where Headquarters Company, Second Battalion had engaged the enemy. They caught several Jap soldiers digging camotoes, which are potatoes, in the field. They killed all the Japs they could see. We unloaded the ammunition to Headquarters Company, and then, being inquisitive, decided to take a look and also see if there were any souvenirs worth taking.

As we looked around, we saw 20 or so had been dispatched and it didn’t appear as if there was anything interesting to sort out. Several of us started back toward the creek bed that we had traveled on all day. Several large trees in the area had been cut down and moved to make the clearing larger enough to cultivate. As we walked towards the creek, several shots rang out. I looked ahead at these felled trees, and I saw chips of wood fly. Whoever this was that was firing was aiming as us! I hollowed out a warning and we all hit the ground. I dropped behind the largest tree nearby. It was about 18 or 20 inches high so I hugged the ground with my head turned back and noticed one of Headquarters men raise up to his knees to the ready with his rifle at port arms. “Bang!” He dropped immediately. As soon as he fell, one of his buddies nearby ran over to him, and as he reached down to help him, he was hit in the head, killing him instantly. Farnsworth, our supply sergeant, had hit the ground in front of me and evidently was sighted by the sniper, as another shot rang out and a huge clump of dirt flew over the log I was behind. Farnsworth screamed someone was shooting at us with an M-1, as he scrambled in a bent-over position into the perimeter. Once inside the perimeter, he was safe as there were enough trees there to hide him from view. It was then I decided to make a move, by removing my pack. I got one arm free, and as I tried to remove my other arm, I dug my toes into the ground and slid forward trying to remove my other arm. Just as I moved, the loudest explosion I think I ever heard went off, and I was sledge hammered in the right shoulder. “Was I still alive?” I suddenly felt hot and weak. I was bleeding and was probably in a little shock. The fact I had tried to get my pack off probably saved my life. The enemy hit me just as I moved, which meant he would have hit me in the head or neck rather than the shoulder. Several of our men had moved up to the edge of the perimeter as they kept talking to me, wondering how I was doing. No one could spot the sniper or snipers, so all I could do was wait. The two Headquarters men behind: One was silent and the other one was seriously hurt, and was moaning. After a few minutes –seemed like an hour – an Aid Man crawled out to where I was. I cautioned him to stay down, but he was fearless. He gave me a shot of morphine and covered my shoulder with a bandage. He said I was hit pretty good, but should be ok. He found the bullet, it was a 30 caliber, and he said he would give it to me after we got back into the perimeter.

The Medic heard the Headquarters man behind us moan, and said he was going to crawl back there and see what he could do. I advised extreme caution; in fact I was surprised we didn’t bring more fire to us while he was working on me. He crawled back to the man behind me. He was lost from my sight but after he got back to where the Headquarters man was, he drew some more fire which meant he could still be seen back there. We remained where we were for a couple of hours, and as daylight ebbed we were able to get into the perimeter. Signor, our radioman from Company Headquarters, crawled out to help me in. Just as we crawled around a huge tree, Cap. Jenkins, Headquarters Company Commander, stuck a 45 caliber pistol my face and demanded the password. I, or course did not have the current password but convinced him, as did Signor, that we were alright. He and a group of his men were on their way out to pick his injured men up. I learned later that the Aid Man who helped me got killed when he went to the aid of the Headquarters man behind me. What a terrible shame. They had set up an Aid Station and Capt. Nestor and Maj. Chambers were helping the injured. Capt. Nester checked and re-dressed my wound. Put me in a sheltered spot and gave me a bit of rations. I tried to rest and think straight, which was difficult. But I prayed. During the night there were grenades exploding and sporadic rifle fire in the edge of the jungle. One of our men made a fatal mistake. He had to go to the latrine. He got up out of his foxhole and went forward instead of to the back to relieve himself. While coming back to his foxhole, one of our men, hearing him coming into the perimeter, shot him. They brought him back to the Aid Station, where he died during the night. How sad. It griped your heart, as he constantly called for his mother during the night, before he left us.

Daybreak was quiet, but as the gray turned brighter, so did the gunfire. It came from three sides. The only quiet side was up the mountainside and that was the way we had to go. Capt. Nestor checked the wounded and saw that we had a little soup for nourishment.. He suggested that I go without pain medicine as I would be stronger without it. I agreed, and we scrambled up the hill – hoping we could do it successfully. The rifle and machine gun fire was strong. Headquarters Company under Capt. Jenkins led the Second Battalion up the hill. E Company brought up the rear and Pvt. Elmer Fryer gave his life covering our movements up the hill. He was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. This was a real ambush and we were fortunate to have just the few casualties we did. We found out later that we were involved with General Yamasito and his personal bodyguard. Had we only known. He was a major war criminal – later executed, I believe. I got hit again that morning by a hand grenade fragment between the shoulders. More an indirect scraping rather than a penetrating wound. All it required was a simple bandage and it healed up without any problem.

We continued up the hill and found our way to Mohonag, where the Second Battalion based our activities. A large Aid Station and Field Surgical Unit were set up. A makeshift hospital area for the wounded using equipment parachute canopies for cover was fashioned. It worked quite well, but it was impossible to stay dry.

The weather continued to be bad, making aerial supply nearly impossible. The pilots took advantage of every little break in the weather, but it just wasn’t enough, and we were short of everything. Food, medicine, ammunition, that made everything extremely difficult. When they did try to drop supplies, because of the terrain, a lot of the material was lost to the enemy and we continued to have men hit when supplies were dropped without parachutes. Food was critical. The men continued to battle the enemy, in spite of making soup out of tree roots, camatoes, and whatever. A small box of K-rations would feed an entire squad of eight men. A stray dog was captured by D Company and quickly transformed into a small deer – butchered and cooked. Those who shared it had good things to say about it.

The walking wounded did our best to lend encouragement to our buddies as they went out on patrols every day, feeling badly that we couldn’t join in. It was not a good feeling – but there was little else we could do. One day Company D and Headquarters Two moved up hill on a large patrol. I don’t know if it was a special mission or just seek and destroy. As they moved out, we gave words of encouragement and silent prayers for success and safety. Shortly after they disappeared from our view, three large reports of artillery fire filled the air. An unusual occurrence, for us as it turned out it was friendly fire from 155 Long Toms being fired from the beach a long ways away. I don’t know who called for the fire. I never did hear. But the rounds exploded in the general area of Headquarters Company as they were moving up the trail. Several of our men were killed and several severely wounded. We lost Headquarters Company Commander, Capt. Jenkins. The Battalion Commander, Col. Shipley, lost a leg as did Pete Cutt, a friend who was on our Regimental Boxing Team. There were other casualties, but none that I knew personally. They were all tragic nonetheless. I never did hear who was responsible for this. The wounded were brought back to our area, and over the next couple of days we watched Pete Cutt die. They were unable to stop his stump from bleeding. We laid him to rest temporarily in our little cemetery up on the side of the mountain. It was a sad time.

General Swing, our Division Commander, with his bodyguard from 188 Glider Infantry, came through on a tour of inspection. We got the word to shave and clean up as best we could before his arrival. It made for a popular occasion. He didn’t spend much time in our area, but we got the word the next day that the walking wounded would be moving forward to the Third Battalion in their area. Part of the 1st Platoon of D Company led us out of Mohonag to join up with the Third Battalion.

The Third Battalion was occupying an area astride the main Japanese supply trail near a place called Rock Hill. This hill was strategic and was hotly contested. A Company of the Third Battalion took the hill and in the process suffered a lot of casualties. Through some mix-up in orders the hill was abandoned and the Japs moved back in. This happened during the night. We then had to re-take the hill and this assignment was being performed when we arrived. The Aid Station area was close to Col. Lathi’s Command Post so we could see and hear the situation as things occurred. A different Company assaulted the hill each day. We heard the rifle and machine gun fire, and the grenades exploding. The hill was about a quarter of a mile away. After a couple of days and many casualties, they blew the Japs back off of the hill. It was not a good place to be.

The Aid Station was full and the surrounding area all occupied by various degrees of wounded. Some died and were removed and buried. One of the returning Patrols brought in a wounded but live Jap. They had discovered him among a few dead after a small firefight. Col. Lathi radioed to the rear to have an interpreter brought up to see if interrogation could develop any worthwhile information. During the night, some one slit his throat. He didn’t make a sound. No one knew who did the job – from that standpoint it was well done. But the Col was hopping mad. Our slogan was yet intact: “We Take No Prisoners”.

It was getting late in December. Maybe this was the reason General Swing came up. Could it be that he would like to see us get out of here by Christmas time? D Company moved through the Third Battalion area of the afternoon of the next day; stopped down the line a short way. The next morning, December 22, 1944, they pulled off their famous “Rat’s Ass Charge”. This was a move of absolute perfection. Patrols had discovered a large group of Japs occupying an area astride the main corduroy road. We never moved in the dark and as a result the Japs had no security out. Capt. Cavanaugh organized a plan of attack that would charge the Japs, using white phosphorus grenades, machine guns carried without the pods so that they could be fired on the run, and ammo belts cut for easy handling. Sudden, noisy victory! Complete Surprise! D Company screamed “Rat’s Ass” – they charged, they killed the enemy. The enemy never had a chance!. Yes, this was picture book. I was not there. But we got orders to move to the beach the next morning, and we walked right straight through this complete devastation. The stories continue sixty years later. All of D Company heroes, Johnie Bitttorie and his machine gun, Taylor, Cushwa, Sepulveda, Sorensen, yes and there had to be a few medals too. How proud I am of D Company.

The march to the beach was literally a dream. Dreaming of a hospital, a shower, a meal and a bed – and not necessarily in that order. Even a bed, with sheets on it. There had to be a dream. We came out at Ocmac under the inquisitive stares of Philippine natives. The wounded were checked out and fed a little before loading us into landing craft. It was now after dark and they moved us down the coast to Bay Bay where we were unloaded and taken to a church which had been converted to a hospital. The next day we were put aboard the hospital ship, Friendship. What beautiful luxury. They cleaned us up, showered us, gave us fresh hospital garb and a clean bed with sheets. Our wounds were dressed. I was X-rayed and they picked a small sliver bone out of my wound and dressed me in a valpo bandage, which eliminated using my right arm. We set sail with all lights lit. No blackout for Hospital Ships. We were headed back to Hollandia, New Guinea, to a General Hospital. It took two or three days to get there. What a beautiful cruise. It took a week or so to get settled in. It was a huge hospital, large Quonset type buildings, two outdoor theaters, comfortable hospital beds, clean, beautiful latrine and shower facilities. Beautiful smiling nurses, striving to see us heal up and get well once again. The Doctors were not as pretty but seemed qualified and attentive. I was in an Orthopedic Ward and they seemed pleased with the way my wound was healing, considering the conditions we were living and fighting in for the past few weeks. I was able to get away from that pesky valpo bandage, which made it a lot easier. Lots of physiotherapy. Jim Stott and Henry Olbyrch were also in the same hospital, so we spent a lot of time together in our free time. Their wounds were rewarding them with a trip back to the States. Stott had a broken arm, and Olbyrch had nerve damage to his right arm. The bullet went right through the muscle, leaving no feeling after severing the nerve. His arm was all healed, but he continued to wear the sling. He was afraid they might change their mind about anything sending him back to the States. It didn’t happen.

After my shoulder healed, I had lost quite a bit of arm mobility as the skin healed attached to the shoulder bone. They decided to give me the necessary movement by operating, scraping the bone and pulling some back muscle forward and attaching it in some way. This was done, and more healing time was involved, which meant I didn’t get back to get ready for discharge from the hospital until March. I didn’t realize it at the time but found out from some of our guys who came into the hospital that I had missed the parachute jump on Luzon. This of course was a great disappointment, but there was still enough action left, as I found out later.

Bittorie showed up one day with a wound in his foot. It turned out that he was ready for discharge at the same time I was. Great! We decided to go back to the Company together.

We went to visit Bob Ingram the morning we left. Bob had been hit in the spine and was paralyzed from the waist down. The prognosis was not good, but we said you never know. We bid Bob a tearful goodby, wishing him well and all the best.

Our discharge papers gave us the authority to travel – sea or water, anything we could get to return to our Company. There was a Replacement Depot located in the area. That was our first stop. We, of course wanted to get back to D Company We made a few inquiries and it didn’t take long for us to decide to hitch a ride at the airstrip. We struck it lucky, finding a Captain flying a C-47 to Leyte. The first leg of the flight was to Palau Island where we stayed overnight and then on to Leyte. We found our way to the 511th Rear Echelon and saw Chaucey Pool who was suffering from a broken leg or ankle and had been left behind when the Regiment went to Luzon. We heard Watson was in the hospital so we went up to see him. He had been evacuated from Luzon. While waiting in the chow there, we got a tropical rain-shower; at the same time it started we heard a plane coming in to land at the local airstrip. We all thought the same thing: “What’s he flying in this shower for?”, and he flew right straight into a mountain that bordered the airstrip. The plane exploded in a ball of fire and we heard later it was loaded with litter cases from Luzon, heading for the very hospital we were visiting. Tragedies of War!

I was thinking of a couple of days relaxation after our plane ride, and we did relax just one day. I went to the movies and then I turned in afterwards. I didn’t know what Bittorie was up to but I discovered later, when he came back to our tent and advised me that we were leaving at first light. He had heard the Company was in need of men so he volunteered our services. He signed us up to leave that morning. We had early breakfast and reported to the C.Q. they got us out to the airstrip and we left on a C-46 loaded with supplies for Clark Field outside of Manila. After a flight of a couple of hours, we arrived at Clark Field and were assembled by a Regimental Officer, loaded into a truck and headed back to D Company, which was still in the general area of Real, Bijiang, I think. They had taken several casualties, included four killed, so I guess they did need some more men. Well, here we were!

We reported to Capt. Cavanaugh who was glad to see us, and we got re-acquainted with our buddies. The next morning we were loaded onto trucks and transported to Batangas Providences – a little town named Iban. We took over a school house and the surrounding area in town, dug in and waited. We had been placed on alert, and had to be with an assigned buddy at all times. We could be in town for stretches of two hours but had to keep in touch with our Platoon area. We never did find out what this alert was all about.

Late in the afternoon of our second day, we got word that a body of Japanese soldiers were spotted off on the edge of town, and Our Company Commander got orders to seek out and destroy. We rapidly assembled, with weapons and ammo – took no field equipment, formed a skirmish line and proceeded to make contact. We filed out of town and across some fields, guarded by trees on the edge. There was a sugar mill about a quarter of a mile away that commanded a view of the area in the direction where the enemy was supposed to be. The CO and his runner went to the sugar mill as the balance of Headquarters were advancing across the field. Suddenly, a barrage of mortar fire filled the air, and my group ran ahead, trying to reach the edge of the trees or the sugar mill for cover. Some men hit the ground. We almost reached the trees when the first shell exploded. It was close and knocked me sideways into the tree. There were several more explosions and then silence. Then rifle fire as D Company began their pursuit. I had been hit several times. I looked around and saw a few others who were hit. D Company filed through us, and Thomas, who was hit in the ankle, and I started to hobble back into town. Ambulances and Air Medics drove out from town and took us to the Aid Station. Thomas had a broken ankle. I had multiple shrapnel wounds as I was hit from the side. My chin, cheek, both arms, both legs, and a pretty good wound in my chest, right above my heart were my injuries. Good thing it was from the side. The funny part of all of this, these were the first sounds of enemy fire that I had heard since my first wounds in Leyte in December. And I was hit again! Ironic!

One of the men who had hit the ground behind us, turned out to be more seriously injured. He lost a leg. He was a new replacement and I didn’t even know his name. They treated us at the Aid Station, held us overnight and then flew us to the best hospital in the area.

The New Bilibad prison. This was a hospital where the Los Banes Internees were taken. In fact, some of the patients were still being treated there. This was the first I had heard of the Los Banos Rescue and it had taken place a month before. I thought this rather strange: I guess the concern is for the moment. We have since all recognized its importance and perfection and point to it as the most perfect Airborne operation ever. They can’t take that away from us. I remained in the hospital about a month and then returned to the Company in Lipa. The Regiment was getting their much-needed rest, and being brought back to strength with the introduction of new replacements. Much needed R & R with passes was being given for visits to Manila were once again the paratroopers of the 511th earned their respect. I continued to have problems with my shoulder that was injured in Leyte. The Medics decided to evacuate me for some serious therapy. They sent me to a evacuation hospital in Manila and much to my surprise evacuated me to the Island of Blak in the Dutch East Indies. I went by boat, and it was like a vacation cruise. They put me in an orthopedic ward and gave me some treatment for some days, then sent me in front of a medical board of Majors and Lt Colonels. They read over my records, asked a few questions about my limited combat experiences, and then dismissed me. I thought this rather strange and when our ward doctor made his rounds the next morning I inquired what this was all about. He replied, “Sergeant, the Board decided to send you back to the States.” This was an unbelievable shock. My true feelings could not be expressed. After the doctor left, I sat there in silence , praying my thank you’s. For me, the war was over. I sailed East to San Francisco, rode a hospital train half way across the country to Percy Jones General Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. While there the bombs were dropped on Hiroshimo and Nagasaki, and the war was over for everybody. Thank God! I was discharged from the Army there on October 2, 1945. The friendships I have made during these years have remained the dearest and strongest of my life. And today can only be expressed as LOVE with the additions of their wives to the great family of D Company. God Bless …

My second wife, Maxine and I first settled in Sebring, Florida, where we enjoyed some good years with good friends and golf. We relocated to Lake Oswego, Oregon several years ago, to be near our daughter, Penny. Sadly, Maxine died in January 2010.

*Together Murray and Maxine had and seven great grandchildren. He was wounded three times in combat and his fellow D Company troopers joked that “no one wanted to share his foxhole after a while.”

Typed by Jane Carrico

Republished WINDS ALOFT Issue 92 Summer 2010

|

|

|

R to L: 1st Lt. Andrew Carrico, III and Sgt. Murray M. Hale speak with a guest at the 2010 511 PIR Reunion held in Reno, NV (Photo by Jane Carrico) |

Cpt. Steven Cavanaugh and Sgt. Murray M. Hale reminisce at the 2005 511 PIR Regimental Reunion held in San Antonio, TX (photo by Jane Carrico) |

If you would like to learn more about Murray's exploits within and the history of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of the book WHEN ANGEL'S FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II, available in the regimental online store, on Amazon or wherever military history books are sold.