T/Sgt. Sorenson, Edwin Leo

3rd Platoon Sergeant, Company D, 511th PIR

June 19, 1921 - December 2, 2008 (Age 87) - gravesite

Citations: Presidential Unit Citation, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Philippine Liberation Medal with service star, the American Defense Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three Battle Stars and one Arrowhead

Edwin Leo Sorensen was born June 19, 1921 in Knappa, Oregon, near Astoria, Oregon "where the Columbia River empties into the Pacific Ocean."

My father’s family was Norwegian and came to Oregon from Minnesota. My mother’s (Gladys Coulter) family was Irish/German, originating in Kentucky and Idaho. The Sorensen’s were loggers. My dad ran the Big Creek Logging Company and I and my two younger brothers grew up in logging camps, riding “speeders” on the railroad track to get to school. We lived and played in the great outdoors.

I graduated from Knappa-Svensen High School in 1939 and went on to college at the University of Oregon.

I was drafted into the army at Ft. Lewis, Washington on July 16, 1942. From there I went to Camp Roberts, California for basic training.

I decided to go to Parachute School before entering the service, and before I learned about the $50/month bonus. With a haircut of the army’s choosing, not mine, I was off to the scorching hot hills of south-central California for 13 weeks. I’d had a year and a half of ROTC infantry training while at college that gave me a grasp of pre-war basics, such as they were, including close order drill.

Soon, all these things came to an end and I was on a train bound for Ft. Benning, Georgia, the parachute infantry jump school. The first three weeks were the normal grind, but my final day meant the usual 4th jump plus the rain-delayed 5th. The night before, we were allowed to have passes, which began as soon as we finished packing our chutes. That meant we hurried, and the usual care was disregarded. The 4th jump was just great – now, I am within one of becoming a paratrooper, - but when I exited I felt no opening shock. I looked up and all the other chutes were heading back up to the C-47, while mine was what you least wanted to see, a streamer. I pulled the opener and about 10 feet of the chute came out and was waving horizontally. I began pulling and pushing it out until about six feet of risers were floating out then I grabbed some in each hand and started spreading and shaking hoping for some air to grab it. After 3 or 4 shakes I was rewarded and I had a very small but welcome shock. Two or three seconds later, the second shock was my feet hitting the ground. Within a few more seconds, I was surrounded by an ambulance, cars, and several people running toward me. I had landed in a depression and no one on the ground had seen the chute open. Much to their surprise I was standing and gathering my chute. I had several bad dreams before I had my next jump.

Immediately after jump school, I remained at Fort Benning for 3 weeks of Communications School. Then in December 1942, I took the short trip to Taccoa, Georgia (where the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment was subsequently formed) for Non Commissioned Officers School. I arrived with a hindrance that was to make my next 6 weeks of N.C.O. School an extremely difficult period in my life. The hindrance was a cast on my right hand and forearm that I had acquired in an evening visit to a nearby (Church Town) better known as Phoenix City, Alabama.

All who completed NCO School were promoted to Corporal, and those of us who had been to Communications School and NCO School were sent to Regimental Headquarters & Headquarters Company. The others went to all the other companies as Assistant Squad Leaders at Camp MacCall, North Carolina.

Upon my arrival in Company “D” of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in early 1943, I was assigned 4 men to train in the use of various radios, telephones, colored panels used to signal aircraft, and whatever else might become available. When the Communications Corporals finished their training in Reg. Hq. & Hq. and were assigned to companies, they were promoted to Sergeant and became a part of Company Headquarters. When I felt the chosen 4 were adequately trained, one was assigned to each platoon and promoted to T5/ Corporal, one remained in Company Headquarters and was promoted to T/Sergeant.

The first weekend after reporting to “D” Company, I had my first confrontation with one of the original Cadre from the 505th P.I.R. He thought I had never jumped so he threatened to remove my shiny new wings. He was immediately informed that any such attempt would result in his backside meeting the floor. “Fearless Phil” then informed one and all that I had in fact earned the “Silver Badge of Courage” and that was that. No more challenges.

We had a series of Company Commanders. Murray Hale hung the name “Short Leg” on Kelly Freeman who certainly earned it. We were on a night compass course in North Carolina and all was well until we entered a swamp that was simply impenetrable, with thorns, briars, vines, and of course water. I had the compass and we were stopped when our leader ordered a 90-degree turn to the right. I thought this was reasonable, as he no doubt meant to go around the obstacle. But after a few paces, he ordered another 90-degree turn to the right. When we exited the swamp no further order was given so we continued blithely on our way back from whence we came.

I cannot remember what I finally did to raise his ire, but shortly after the compass fiasco I was reduced to Private and stayed at that level until we went to Louisiana and Freeman went on furlough. It was then that Lt. Solomon was in charge and went on the infamous rampage of 3 inspections every day. At least he kept us busy. Then one day someone asked me if I had seen the bulletin board, and if not, I should go look because my name was on it. I went to look and my name was on three sheets of paper. The first showed a promotion to P.F.C., the next was a promotion to Corporal and the third put me back to Buck Sergeant. When Freeman returned, he tolerated me until New Guinea when this red-head, Steve Cavanaugh, showed up as our new Company Commander. What a breath of fresh air!

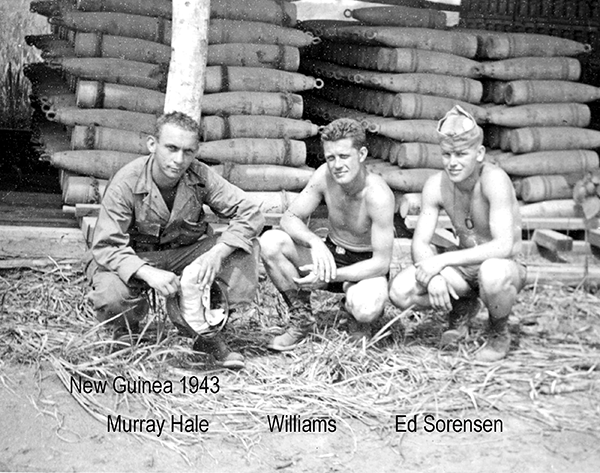

In May 1944, we were ordered to pack our bags as we were leaving for our Port of Embarkation. We wondered-- were we headed for Europe or the Pacific. We loaded on a train and headed north, waiting anxiously to see if it turned East or West. West won. We arrived in Camp Stoneman, CA, removed our insignia and told we would have no passes and were not to divulge any information about ourselves to anyone. I understand that order was not obeyed to the letter. We were issued a lot of new clothing and new weapons. In short order we were taken to the Docks and loaded onto the infamous Sea Pike – a filthy stinking ship that was fast enough that we needed no convoy as we proceeded first to Port Moresby, New Guinea. It was such a surprise to us, as it was night, and unlike in the blackouts in the States, powerful lights were on everywhere. We were guided into Port and left the next morning, as I recall, for Dobadura, New Guinea which was to be our home away from home for the next several months.

New Guinea produced incredible amounts of boredom and bad food. The bad food spawned some excursions that were masterpieces of fairly good planning and outstanding good luck. About a half dozen of us would leave camp about dark and hitchhike a few miles until we were close to a food depot encircled by a barbed wire fence and patrolled by a single guard who walked the outside perimeter. After timing his trips around the depot we entered and made our way inside the dozens of stacks of various foods. Once we had the stacks to hide behind, we could safely light matches to determine what composed each pile of canned goods. We had to know what we were taking, for fear of getting back to camp with cases of Spam or Australian goat meat.

New Guinea produced incredible amounts of boredom and bad food. The bad food spawned some excursions that were masterpieces of fairly good planning and outstanding good luck. About a half dozen of us would leave camp about dark and hitchhike a few miles until we were close to a food depot encircled by a barbed wire fence and patrolled by a single guard who walked the outside perimeter. After timing his trips around the depot we entered and made our way inside the dozens of stacks of various foods. Once we had the stacks to hide behind, we could safely light matches to determine what composed each pile of canned goods. We had to know what we were taking, for fear of getting back to camp with cases of Spam or Australian goat meat.

When all was ready, two of our group would walk about a quarter of a mile down the road, but away from camp, to assure ourselves of a ride. They would flag a truck down and ask the driver if he would take us, and our few boxes of good food to our camp, in exchange for a case of peaches. So strong was the lure of something decent to eat, we were never turned down. To my knowledge, no one’s conscience ever suffered.

I think I have read the following anecdote in “Winds Aloft”magazine, and I’m just as sure it will be retold several times by our remaining “D” Company comrades – the night all hell broke loose and brought every officer in the Regiment, and probably some others. That was the night that easily 10,000 rounds were fired without a single confirmed kill. The enemy was the multitude of huge bats that flew over at dusk every evening. The result was that our ammunition was taken away and admonishments were the order of the day for a week or two. I suspect that a number of officers sneaked back to their tents chuckling to themselves.

Weekends were generally free so a few of us, Red Zadorian, Chick Williams, Murray Hale, myself and others I can’t recall, would scrounge some food and head for a favorite spot we had found at, or near Buna. There was a small shack on the edge of the beach that had sides, a roof, but an open front facing the beach. One particular morning Chick and I woke up first and he decided to go for a swim. I sat on the floor watching him when I saw shark fins in the water near him; he began shouting and scrambling for the shore. His cries awakened everyone by the time Chick was safely out of the water. He had been bumped by at least one shark but suffered no harm. Again all hell broke loose as we began firing at the fins darting about. Finally someone hit a fin and as the blood began to taint the water, the wounded shark was attacked by his mates. None of us ventured out to see if there were any remains.

By this time our Table of Organization had changed, and each Platoon was to have a Platoon Guide who was to be a Staff Sergeant and the Platoon Sergeant was promoted to Tech Sergeant. I was promoted to Platoon Guide under Sergeant Barriero in the Third Platoon.

All of us were beginning to wonder if we were ever to see combat, as several months had passed with no indication of movement. About two weeks before we left New Guinea, Chick Williams and I learned of an item that could be had for 14 pounds Australian. It was one that his father had taught him to operate and was sure to make the two of us independently wealthy – a copper Still in good working order, ready to go. We moved it far back in the kunai grass away from Camp, near hills and water. We talked to the Battalion baker and for all the booze he wanted, we were given the ingredients we needed. We caulked M1 boxes, a couple barrels, etc. and mixed the first batch. I was anxious to check to see how our production was doing, but Chick who was an old hand at this, said there was no hurry; it took at least 10 days to start working. Chick was from Boston and made a mistake when he failed to take into consideration the difference in temperature in New Guinea. Before arriving, our sense of smell told us something was awry – and was it ever! There was a sea of foam 4 feet deep and at least 30 feet in diameter. But, it didn’t matter because a week later we were on our way to the island of Leyte, in the Philippines.

We landed on the shore of Leyte Gulf near the town of Abuyog, and the battle for the skies began shortly thereafter. There were hundreds, if not thousands of ships, boats and landing craft scattered for miles, as the Japanese began an incredible air assault that continued on and on. I was in awe as I watched four P-38’s go up through the Japanese planes and start one or two of the enemy on their fall to the sea. They then would make a big loop, come back down and send two or three more to their doom. This slaughter continued as long as our planes’ ammunition lasted.

One day, I was walking along the beach when a Japanese Zero, on fire, came from inland, heading for ships in the Gulf. The Zero was no more than 200 feet high, and close enough that I could see the pilot and flames in the cockpit. He headed for the largest ship near the beach and dove for it. Luckily he missed, but had been so close that water splashed on the deck. I could see sailors running toward the plane with fire hoses to wash the burning fuel overboard. What a sight to behold.

The day soon arrived when we put all our clothes except the ones on our backs in duffle bags and stored them near the beach under coconut trees. It was the rainy season in Leyte and we wouldn’t see those bags again for over a month. Our musette bags were filled with extra food, ammunition and all the extra gear we expected to use for how long we knew not. We loaded into trucks and headed north to Tacloban, and the steep and muddy mountains, carrying the heaviest packs I had ever shouldered. How anyone could have fought burdened with such a load was beyond all of us. We started up the first of hundreds of ridges and mountains that covered the bulk of Leyte’s land mass. Our first break was called and the unloading began. Our 3rd Platoon runner, Hagemeyer, was just ahead of me and as his discards were chosen, he called out what it was and tossed it aside. I shall never forget when he pulled one item out, pondered it for a time, and called out “Goodbye Good Book”, and put it – the Bible – gently on the ground.

When we moved again, our loads were lighter and our outlook much brighter. I believe it was our first night in the mountains when we stopped beside a beautiful stream and bathed in a large pool. My pool-mate was none other than Colonel Haugen who was in the happiest mood one could imagine. We had followed the First Battalion, and he had been with them when they had the first 511th skirmish. He kept saying over and over to me: “They’re fighting sons-of-bitches”, showing his pride in what he had instilled in what was to be the army’s finest Regiment!

We proceeded through the mountains and at late afternoon of December 7, 1944 we stopped on a grassy hilltop where we could see Ormoc, Leyte. We then watched our Navy shell the Japanese troops in that area. This was where we suffered our first killed in action, Richard Mills. He was struck squarely in the chest with a box of “C” rations dropped from a plane flying very low overhead.

“D” Company’s first skirmish found us in a valley with a farm and a small stream flowing through it. A few men and I went down to the stream to fill our canteens. Coming upstream and around a bend were 8 or 10 Japanese. We ran back up the bank and waited for them as they had not seen us. When they got close we opened up and killed them all. What we did not know was that there were many more Japanese nearby and soon they were firing on us. We started running, when I did something I never have understood. I found myself sitting on a small rotten log when a round struck squarely between my legs and I felt the tiny upheaval. The next few seconds found me up and running back to the safety of the company. I thought I knew approximately where the shot came from but I couldn’t spot him. We lost one man, Pickens, during that sleepless night. The next morning, Steve Cavanaugh, asked us to scout a muddy corduroy trail to the top of the mountain. (corduroy means short small logs placed crosswise in the trail bed) and report what we found. My background of having lived in logging camps where I hunted-fished, trapped and worked gave me as advantage in such a situation. I could see tracks, (in this case sandals,) and tell quite well how old they might be. I knew that many of the ones were quite fresh as there was muddy water in them. It was slow going as I insisted on no speaking and as little noise as possible. We reached the top and found three dead Japanese. They were quite fresh so I went to each one, put the muzzle of my grease gun to each one’s head and felt his throat – all were cold. When we moved further the lead scout who was a few steps ahead of me, was shot. He came running back-was OK Much to my joy, I looked back and saw Cavanaugh and the rest of the Company.

Somehow we skirted the enemy and continued on without incident into the night. I have never known how Steve Cavanaugh got us through the timber and stopped us barely short of our own peoples’ booby trap line. We talked to them and some of our guys came out, deactivated the grenades and let us inside the perimeter. It had been raining for hours and when we were told to flop down wherever we could, I collapsed with fatigue, felt water running in and out of my collar and didn’t care. I just went to sleep for our first of many nights in Mahonag.

Photo at Right: L to R - Pfc. Lesley E. Valentine, T/Sgt. Edwin Sorenson, S/Sgt. Leonard Klein, Pfc. Charles B. Williams share drinks of coconut water near Mahonag, Leyte. Photo by Pfc. Norman Zadoorian

Photo at Right: L to R - Pfc. Lesley E. Valentine, T/Sgt. Edwin Sorenson, S/Sgt. Leonard Klein, Pfc. Charles B. Williams share drinks of coconut water near Mahonag, Leyte. Photo by Pfc. Norman Zadoorian

Our ammunition began to run low, as did our supply of “K” rations. We rationed our food; first day, one meal divided between two men; the next day one meal for five men. The last day for our platoon I remember dividing two meals so that each one served 13 men. We had been able to supplement this with camotes (a potato-like root vegetable) that were soon gone. A rifleman in the third platoon came to me one day and asked permission to go just outside the perimeter where he was sure he could kill a deer. Deer leave tracks and I had seen none in the miles of muddy trails we had traversed. For that reason and others, I denied his request. He didn’t want to give up so he smiled, winked at me, pulled out his knife and called the dog that had followed us from the lowlands. He assured me he would make no noise. In about an hour he came out with a tiny corpse minus its head, tail, paws and skin. Who was to know it wasn’t a deer? With what was nearly the last of the camotes, we had what passed for a fine stew. I don’t know how many others we shared this with – we wanted everyone to have a bite, but no more. It wasn’t bad.

About this time the Third Platoon was sent to replace a platoon from “E” Company that had an outpost a short distance from Mahonag. I was uneasy about this and told Lieutenant Walt Kennely that I felt I wouldn’t come back from this assignment. He patted me on the back and assured me that all was well. He was correct, for it was just a few minutes before a concussion grenade landed at my heels and flipped me up and over so that I landed hard on my left shoulder with my feet straight up in the air. Lipanovich, who was walking behind me told me later that as I was falling, I had the strangest expression on my face. I didn’t remember getting to my feet, but I knew that the battle was on. It seemed apparent that a number of Japanese were in the trees and practically impossible to locate. However, they weren’t all in trees, because Chuck Wise, who was behind me said: “Ed, look to your left”. I did, and about 30 feet away was this fellow putting a cover back on a foxhole he had just exited. I was carrying a grease-gun with thirty 45 caliber rounds in the clip. I jabbed the clip in the ground, sighted, pulled the trigger and never stopped firing until every round had been expended. Now this was a perfect example of “buck fever” at its worst. It was a terrible day for “D” Company as we had three Killed In Action (K.I.A.) and several Purple Hearts. Al Barriero, the Platoon Sargeant was one of the dead. We never made it to the outpost.

We returned to Mahonag and finally got an air drop of food and ammunition. The drop was by parachute and many were far enough away that the Japanese got to them first, and enjoyed some of our food, which they no doubt needed as badly as did we.

Shortly after this we moved out and headed for “Maggot hill”. This is when the artillery shells landed on us, causing many casualties. This aptly named area was simply crawling with maggots that had been feasting on the bodies of dead Japanese. We were there for one Sunday during which a Catholic priest said Mass while standing in a foxhole. Sadly the Mass was incomplete because there was no fruit of the vine.

There was a very narrow ridge top leading from Maggot hill toward the town of Ormoc, maybe three or four feet wide, with a precipitous drop-off on either side. This was for about 100 feet before it broadened out. It was essential that the 511th get across this impediment. The daily assaults began on December 20th in the face of a withering fire from the defending Japanese. Our losses were severe, but deemed unavoidable. Other companies had suffered badly until it became ”D” Company’s turn. Captain Cavanaugh called us together, told us our turn was to begin the next day and that we would use a tactic that had been the exclusive province of the Japanese. We were to move in on them at the crack of dawn. It turned out to be what I have always thought the most critical decision made in Leyte by the 511th. In the forefront was lead scout David “Red” Iles. He made it across so silently that the enemy was caught completely by surprise. The first Japanese he saw were just beginning to sit up and stretch. It was the last time they ever woke up because Red popped them. As soon as Red fired, the push was on, since more of our troops were crossing and spotting the still drowsy enemy. In a matter of moments, I heard the originator of the famous saying: “Rats Ass”, Dave Vaughn shouting those words over and over.

Since that time, the rest of that day has been referred to as the “Rats Ass Charge”. However, there has been a denial that any such thing as a Charge ever occurred. The denial came from Red Iles, who should know, but my belief is that the argument is simply of semantics. We were trotting, double timing, sometimes running from side to side as the enemy dispersed. Red told me that he chased the Japanese until he felt he could no longer continue so he told the second scout to take over the lead for a while. Then the pace slowed which caused Red to take the lead once more. He felt slackening the pressure could be deadly. Now, as for the semantics, I feel that Red thought that what the “Light Brigade” did was a Charge, and that unless we were running full speed, it was not a charge.

I have a very dear friend who has long felt that John Bittorie should have received the Congressional Medal of Honor for that day. Bittorie was an excellent soldier and certainly was my friend, but from start to finish of that day, Red Iles, in my opinion, was more deserving. It took great courage to cross that heretofore deathtrap of a narrow ridge top and then to continue charging right at them. (Sorry. R. A. but I still love you.)

We finally stopped when we came to a jungle of palm, mango and papaya trees. After the General took his favorite regiment to the beach, we had to stay in the hills for three more days and carry supplies back for the rest of our Battalion.

Our reward when we finally got back to Abuyog was to find our clothes all rotted. After a few days of having our jungle rot treated and getting new clothes, we flew north and west to the Island of Mindoro, which is close to the southern tip of the Philippines’ largest island, Luzon. There we waited for the C-47 cargo planes to assemble, and to learn where we were headed next. We took off for Tagaytay Ridge overlooking Lake Taal on the island of Luzon. Those of us who were to be jumpmasters were given a list of checkpoints along with the exact time of arrival at each one. As I sat on the equipment bag looking out the open door to spot the checkpoints as each appeared exactly on time, and with a few minutes remaining before the drop zone, men on the right side of the plane began shouting: “Ed, they are all jumping!” My decision was to join the rest, so out we went into a sea of fog. When I landed I was in a large tilled field surrounded by trees, but with no one in sight. About once a minute I would hear a single shot and wonder if someone had been shot, or were they signaling. Finally I found first the equipment bag, and then one man after another. We found our way to a road and then uphill to the original drop zone.

The next day trucks arrived and we were on our way north to Imus, and an interesting encounter with the enemy. Cavanaugh and I were together peeking over a stone fence looking at what could be called a barracks, but was really a warehouse built of two-foot thick stones. On the west side, about 75 feet from the building was a hedgerow of brush. Cavanaugh said: “Ed take a few men, go behind the hedgerow then cross to the building. Wait till the M-18 tank mount goes to the far end, south, and fires ten rounds into the building, and then go in”. Of all those with me, the only person I remember was John Bittorie.

We approached the northwest corner where we were to enter a door about 3 feet wide. When we reached the door I stood right next to it and waited for the ten rounds to be fired. The inside was so dusty I could not see anything. It was about 2 feet from the door to the north wall, so I fired three or four rounds and then called each man in. John Bittorie came last because he carried a BAR automatic rifle. I was to be happy about that. While we waited for the dust to clear, we saw several window openings about 3 feet above the floor. As I came out of the second empty room, Bittorie was laying across one of the window openings on the far side from me, with his BAR firing from a position that reminded me of a pool player reaching across a pool table to make a crossways shot. I looked at the window to John’s left and saw 8 or 10 Japanese falling like hay before a mowing machine. Our guns were shooting from every window. I’m certain that every one of the enemy on that side was killed. When we exited the building through a door made for trucks to enter, the building was secure.

We took off walking fast and after a bit came to a small town where the Filipino townspeople were waiting to welcome us with a small band. I enjoyed it because their hearts were obviously in it. They were happy at last. About dusk we came to a bridge over the Pasig River but the Japanese were defending it. We waited for the next day to kick them out. Our progress into southern Manila was slow and difficult. The Japanese, believing that the Americans would attack Manila from the south, had it heavily fortified, and pretty much neglected the north.

Moving toward the Genko Line we saw numerous mines in the roadway, easily spotted and avoided. When we got to the Line, we stopped and called for a tank mount to come forward and shell the obstructions. A tank soldier walked alongside to guide the tank around the mines while we sat off to the side in the shade. When the tank withdrew, the guy guiding it, let it back over a mine, killing him and those inside.

The Genko Line itself, where it crossed the highway, consisted of two rows of piling with small tractors, trucks etc. between them. Barbed wire was strung everywhere. On the enemy side were heavily manned pillboxes with less than adequate low level sight lines. Our Third Platoon bazooka man, whose name I have forgotten, crawled in a ditch right up to a pillbox, put the muzzle through the opening, pulled the trigger, and nothing happened. He had carried the bazooka all through Leyte and now to Manila. When it came time to use it, the fool thing failed him. He crawled all the way back, threw the bazooka on the ground, and actually crying, shot it full of holes. I crawled up to within a few feet of the line. It consisted of barbed wire with mines that were quite evident. I considered shooting at the part I could see sticking above the ground, but after a moment of reflection, chose not to do it.

When we finally made it through the Genko Line, we called for heavy artillery fire from the First Cavalry Division. An eerie sound as the rounds approach you. As we continued on, the First Platoon and Company HQ were on the right near the highway; the Second Platoon in the middle moving through burned over ground, and our Third Platoon on the left searching through countless Filipino homes amid heavy brush and small trees. Every one of us, including our machine gunners and mortar men were going alone into homes. I came out of a house and started down a dirt path. I saw a man jump across a very narrow opening. I paused, trying to decide whose uniform that fellow was wearing. That was almost a fatal error as a round came whistling by my right ear. I was so close to this fellow that my only choice was to charge him, firing my MI as fast as I could pull the trigger. When I reached him, he was gasping his last.

The fighting continued in this manner as we pushed forward, seeming never to run out of Japanese. The next day in a similar situation, I was on the right side of the platoon when Larry McLain came running from the left, showed me his knuckle and laughingly said: ”Look Ed, I’ve been wounded” (he pronounced it like a clock being “wound”). I sent him crawling, because of heavy enemy fire, to help Chester Smith, who was in a forward position, and who soon was seriously wounded. Larry apparently tried to drag Smith back and in doing so, exposed himself and was killed instantly. Roy Streck and I and two others I cannot recall got Smith out, left Larry, and ran with Smith to get a medic for him. I believe we ran at least 150 yards until utterly exhausted.

I and two other men returned to the scene later to retrieve Larry’s body. It was one of the most difficult times in my life. An elderly Filipino man showed us where he had buried Larry’s body. He had made a cross of two branches from a tree and put them on Larry’s grave. The main thought running through my head at the time, in retrospect seems silly to me now, as I stared at the mound of dirt covering my beloved friend. It posed a serious problem. Where do I begin digging, because Larry, I cannot bear pushing the shovel in your face? I dug very carefully and avoided what had so concerned me then, and as I write today, still brings tears to my eyes.

We had been warned time and time again about the Japanese wearing Filipino clothing in order to get close to us, and then opening fire. I was faced with the dilemma once in Manila as we broke out of the housing and onto the edge of a beautiful park running along Dewey Boulevard: at least 100 hundred people came streaming out from among the shrubs and the houses. I immediately ordered a skirmish line with machine guns in place and riflemen prone and ready. My order was also that there be no firing until I fired the first shot. The people were no more than 100 yards away when they began running in our direction. I looked at them as they neared, and thought: “My God, if I am wrong I am really wrong, so hope for the best”. It WAS the best. They were not the enemy.

This was the end of our fighting in southern Manila so we moved on toward Fort McKinley. Our first glimpse of the fort was across a huge field – grass, with very few trees. The distance to the fort was 3 ¾ miles. How do I know? A tank with 105 mm cannon stopped beside us and when I asked, the tanker said 6500 yards.

We started moving with what was the longest skirmish line imaginable. I believe that virtually the entire Regiment was on line as we started toward McKinley. What a sight, and it was to become even better. We were on the left edge of the Regiment, moving up a gradual rise near a small grove of trees. A burned out WWI American tank lay on its side among the trees. A lightly graveled road with a 5-foot hedgerow, ended about even with that tank. Cavanaugh told me to take a couple of men, and make contact with the First Cavalry. He pointed out the general direction, so off we went much faster than double time. Probably a mile later we found the First Cav and reported our position to a Brigadier General whom I was to admire greatly and never forget, though I never learned his name. He was directing fire from the First Cav’s heavy stuff – the 155’s. All the while, a magnificent show was taking place. The Army Air Corps used high-level, medium-level and dive bombers along with fighters strafing the enemy, who were apparently blowing up their ammunition dumps with plumes of red dirt shooting hundreds of feet in the air. Following each blast, the concussion could be followed visually as it came toward us pushing over the two to three foot tall grass, which would then spring back up.

A memory gap here for me, until we start down the east side of Calumba deBay. When we reached the sugar mill town of Calumba, we paused for two or three days to settle a problem with the Japanese over who should control nearby Mount Bijiang. “I” Company had started before us and had chosen a frontal assault through the burned over and very steep eastern face of the mountain. Cavanaugh, on the other hand, chose to take us up the northeast cover where we had adequate cover and could move unopposed. “I” Company was in a stalemate and completely unable to move. When we reached the top, we still had some cover until we reached a tilled field across which we could see the enemy moving about still oblivious of our presence. On our side of the field, there was a vertical drop of about 30 inches with a fringe of grass on the top edge giving us perfect cover, but still allowing us to see movement of the enemy. Cavanaugh had one platoon (not mine), filling that position. My platoon moved to the right flank, to the edge of a tiny draw, that started at the edge of the tilled field, and dropped for about 20 feet.

In a tiny area at the head of the draw were a half-dozen trees that blocked any view of the bottom. Then there was a narrow dirt trail up the opposite side, where the top was level with our position. The trail was very steep, with short shrubs growing on both sides and closing together at the top. I loved to use phosphorous grenades, so I threw one into this hole in the ground. Guess what – two or three Japanese trotted up the trail from me, no more than 30 to 50 feet away. I began shooting as they reached the top. I had two more grenades and each one I threw brought 2 or 3 more of the enemy. So I had me a shooting gallery. The foregoing sounds very well, but I followed that with the worst sin a platoon sergeant can commit. I sent a very bright young assistant machine gunner to a position about 20 feet away from me, expecting him to be covered by the trees at the head of the draw. I was wrong, and no sooner had he put the tripod down than he was dead. I stared in disbelief, and have shed tears for this young man that I did not have time for, as he lay dying.

I went back to check with Cavanaugh, and found him bleeding profusely. As I talked we learned that every officer had been wounded. Carrico had lost a finger and was in much pain. The others wounded I cannot remember. Cavanaugh said to send the 1st Platoon 50 yards down the hill, form a skirmish line; send the 2nd Platoon another 50 yards, form a skirmish line, take the 3rd Platoon another 50 yards and form a skirmish line; check each platoon as you pass to see if everyone is present and continue this to the bottom of the hill. When I checked my 3rd Platoon, we were 2 short. I thought they were still on the top so I shouted “Streck come with me”. Roy and I went back and looked all over, finding no one. We found the two had gone all the way back to the bottom.

I was again where I had been most of the day until I saw Japanese in white uniforms running through the short shrubbery in a direction that meant they were outflanking us. Our mission was complete for the time being, as we executed the maneuver known as “Get the Hell out of here”.

Other troopers supplied information on the saga of Mt. Bijiang. I think that my story is long enough.

(Added by Eileen Sorensen) From a hand-written letter from Ed Sorensen to his parents, September 10, 1945, from Japan:

(Added by Eileen Sorensen) From a hand-written letter from Ed Sorensen to his parents, September 10, 1945, from Japan:

“Our outfit spent a little more than 3 weeks in Okinawa en route to Japan. News arrived that the Japanese had torpedoed the battleship “Pennsylvania” and that lots of sailors were lost. The ship had been towed to Okinawa. I needed to know if Gerald was OK (Gerald Sorensen, Ed’s younger brother). Four of us went out to see the ship at three in the afternoon. We found Gerald was OK. I spent the night with him and actually spent two watches with him (one at 3 in the morning). The ship was supposed to leave for Guam at daybreak, and we were really sweating it out, until an LCM came alongside and took us off. Our outfit was on a 10 minute alert but they were still there when we got there, and all was OK”.

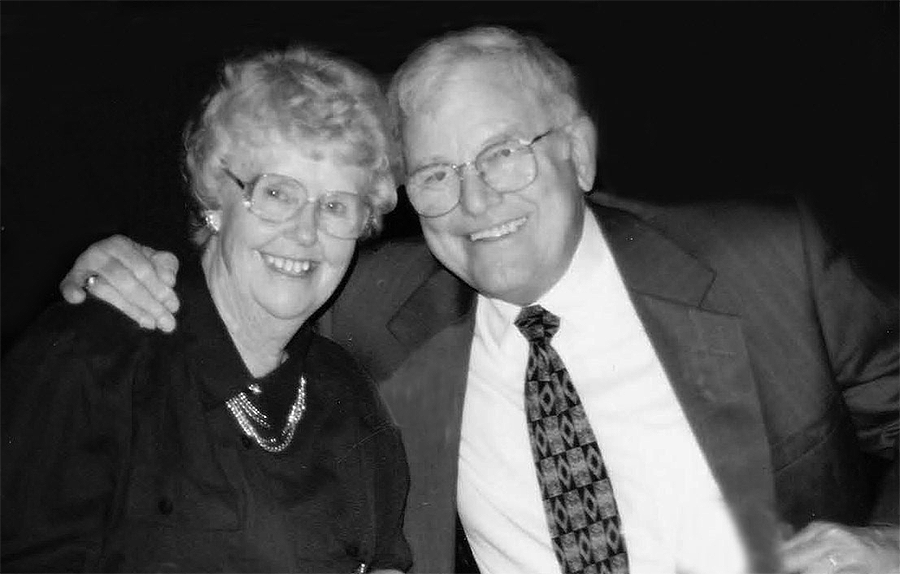

Ed returned to private life, after the war, and married the wonderful woman of his life, Eileen. Ed died December 2008.

Story compiled by Ed Sorensen

Type by Jane Carrico

To WINDS ALOFT Feb 2010.

Official Obituary:

Funeral Mass for Edwin Leo Sorensen will be at 11 a.m. Saturday, Dec. 6, 2008, at St. Pius X Catholic Church on Saltzman Road in Cedar Mills.

Known as "Ed" to his parachute comrades, and as "Leo" to his family and friends, he died at home in Aloha on Dec. 2, 2008, after goodbyes from many loved ones.

Born June 19, 1921, to Ed and Gladys Coulter Sorensen in Astoria, he lived in a logging camp while attending Knappa High School. After attending the University of Oregon in 1939-40, he returned to his roots, the timber industry, and worked as a gyppo logger until World War II. In late 1942 he was drafted, and after basic he opted to go to parachute training. He became part of the new 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment, specifically in Company "D". The outfit was sent to New Guinea in late 1944 and then was part of the Leyte Island and Manila, Luzon campaigns in the Philippines. He also participated in the rescue of 2,100 American prisoners in Los Banos, Philippines on Feb. 23, 1945.

In 1948 he married Barbara Smith. They had three children, Debbi, Ed and Erik Sorensen. They later divorced.

After the war, Leo returned to logging. He was seriously injured in 1964 when a bridge on the Salmonberry River collapsed while he was driving a caterpillar over it. He then returned to college at Portland State University and graduated in 1970. Before graduation he served in Governor McCall's office and then the Housing Authority of Oregon. Later he worked for Multnomah County.

After that, he then started an entirely new life as a manufacturing representative for "Sign of the Crab" - a fine company specializing in brass plumbing products. He often remarked that this is what he should have been doing all along. On Valentine's Day, 1976 Leo married his beloved, Eileen Moore. He is survived by Eileen; two children, Debbi and her husband, Doug, Ed and his wife, Michele; grandchildren; and a great-great grandson. His son, Erik, died in 1978 at age 20.

Leo would want all of his surviving comrades from Company "D" to be honorary pallbearers, scattered though they be.

He would like any desired remembrances to be sent to the Oregon Food Bank, to Blanchet House of Hospitality, or to their church community, Mission of the Atonement.

Gratitude is expressed to the caring personnel of Kaiser Hospice group.

If you would like to learn more about Ed's exploits within and the history of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of the book WHEN ANGEL'S FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II, available in the regimental online store, on Amazon or wherever military history books are sold.