The Aparri Landings: Gypsy Task Force 76 Years Later

For years now I have been reading and listening to articles and podcasts mistakenly claiming that Operation Varsity (part of Operation Plunder) was the last airborne operation of World War II. While Varsity was indeed an enormous campaign that involved over 16,000 paratroopers and thousands of aircraft, it was not THE last airborne operation of the war, though in can correctly be called the last one held on such a massive scale (Varsity was the largest single-day/single-location airborne deployment in history).

For years now I have been reading and listening to articles and podcasts mistakenly claiming that Operation Varsity (part of Operation Plunder) was the last airborne operation of World War II. While Varsity was indeed an enormous campaign that involved over 16,000 paratroopers and thousands of aircraft, it was not THE last airborne operation of the war, though in can correctly be called the last one held on such a massive scale (Varsity was the largest single-day/single-location airborne deployment in history).

So, if that is the case, what WAS the last airborne operation of World War II? Answer: The 11th Airborne Division's Gypsy Task Force.

Operation Varsity kicked off March 24, 1945 in Wesel, Germany whereas the Angels' landings at Aparri, Luzon, P.I. occurred on June 23, 1945, almost three months to the day after Varsity. For decades, members of the 11th Airborne Division have heard erroneous reports stating that their brothers in the 17th Airborne Division were honored with "making the final jump of the war", but that credit actually belongs to the Angels. In addition, the 11th Airborne was scheduled to drop on Japan during the anticipated Operation Olympic in late 1945, a campaign that was thankfully aborted due to Japan's surrender. This cancelled drop would have put the Angels' last airborne deployment even later than Varsity, likely around November of 1945. But let's dig in to the actual LAST airborne deployment of the war, the Gypsy Task Force.

Origins of The Gypsy Task Force

While Nazi Germany officially surrendered to the Allies on May 7, 1945, the 11th Airborne Division was still busy fighting an indignant Imperial Japan in the Philippines. Yes, there were some in Japan's governing bodies who were leaning towards surrender as victory was becomming an increasingly hopeless prospect, Imperial forces were still fighting bloody battles across the Pacific. It is so easy to forget that while countries around the world were celebrating VE Day on May 8, 1945, Allied forces fighting in the Pacific Theater were still fighting or getting ready to launch the bloody campaigns to retake Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Luzon and Mindano. While shouts of "Peace! Peace! Its over!" rang throughout the streets of Europe, the Pacific war went on and continued to cost the Allies over one-hundred-thousand casualties.

In May of 1945, AFTER VE Day, the veteran 11th Airborne Division was still heavily involved in the battle to liberate the island of Luzon in the Philippine Archipelago. Under the command of Major General Joseph May Swing, the Angels had fought their way from Nasugbu on the island's west coast, up towards Tagaytay Ridge where the division's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment made a parachute drop on February 3, then the division pushed north to participate in the brutal Battle for Manila. For a complete description of this campaign, please consider purchasing a copy of our book on the 11th Airborne, WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II. The Angels suffered heavy casualties in the fight to retake the city and then in their ensuing operations to retake the mountains and cities of Luzon's southern and southeastern sectors.

In May of 1945, AFTER VE Day, the veteran 11th Airborne Division was still heavily involved in the battle to liberate the island of Luzon in the Philippine Archipelago. Under the command of Major General Joseph May Swing, the Angels had fought their way from Nasugbu on the island's west coast, up towards Tagaytay Ridge where the division's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment made a parachute drop on February 3, then the division pushed north to participate in the brutal Battle for Manila. For a complete description of this campaign, please consider purchasing a copy of our book on the 11th Airborne, WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II. The Angels suffered heavy casualties in the fight to retake the city and then in their ensuing operations to retake the mountains and cities of Luzon's southern and southeastern sectors.

Things slowed down a little for a few weeks in early June when the Angels were given some time to rest and recuperate, plus integrate badly needed replacements. The division as a whole suffered 18% casualties, higher than most infantry divisions in the PTO; some of General Swing's companies had endured 70% casualties. Their short rest, however, would not last. The Japanese were still waiting in defensive pockets spread throughout Luzon. One of those pockets was centralized in northern Luzon and there was some concern was that the remnants of Japan's 150,000-man "Shobu Group", what was left of General Tomoyuki Yamashita's 14th Army, would make its way north towards the coast where perhaps the Imperial Navy could effect some sort of Dunkirk-like rescue.

As it stood in early June of 1945, Yamashita (seen in the photo to the right) had already begun enacting the abandonment of the Cagayan Valley itself with a withdrawal into the Cordillera Central. The general planned to spread his forces throughout three defensive perimeters around Luzon's fertile Cagayan Valley which, like an inverted triangle, was encircled on the north by the Babuyan Channel, on the west by the impressive Cordillera Central hills and to the east by the Sierra Madre mountain range. Nicknamed the "Tiger of Malaya" and "The Beast of Bataan", Yamashita had deployed the Shobu Group well around the large valley's perimeter that was a natural stronghold full of gorges and razor-backed ridges and mountain tops. To give his men time to gather and stockpile resources from the valley itself, Yamashita was coordinating a slow "war of attrition" rather than decisive actions with forces that consisted of the 19th Division, the bulk of the 23rd Division, and elements of three others: the 103rd and 10th Divisions and the 2nd Tank Division. Both sides knew that the longer the Japanese had to prepare their defenses, the more casualties it would take to reclaim the Cagayan Valley and the surrounding mountains. It would also allow the enemy to stockpile provisions taken from the productive area since the US Navy had cut off all amphibious enemy resupply (although, again, a Dunkirk-like rescue was a concern, though highly unlikely).

As it stood in early June of 1945, Yamashita (seen in the photo to the right) had already begun enacting the abandonment of the Cagayan Valley itself with a withdrawal into the Cordillera Central. The general planned to spread his forces throughout three defensive perimeters around Luzon's fertile Cagayan Valley which, like an inverted triangle, was encircled on the north by the Babuyan Channel, on the west by the impressive Cordillera Central hills and to the east by the Sierra Madre mountain range. Nicknamed the "Tiger of Malaya" and "The Beast of Bataan", Yamashita had deployed the Shobu Group well around the large valley's perimeter that was a natural stronghold full of gorges and razor-backed ridges and mountain tops. To give his men time to gather and stockpile resources from the valley itself, Yamashita was coordinating a slow "war of attrition" rather than decisive actions with forces that consisted of the 19th Division, the bulk of the 23rd Division, and elements of three others: the 103rd and 10th Divisions and the 2nd Tank Division. Both sides knew that the longer the Japanese had to prepare their defenses, the more casualties it would take to reclaim the Cagayan Valley and the surrounding mountains. It would also allow the enemy to stockpile provisions taken from the productive area since the US Navy had cut off all amphibious enemy resupply (although, again, a Dunkirk-like rescue was a concern, though highly unlikely).

And while the Ohio National Guard’s 37th Infantry, the “Ohio/Buckeye Division”, was tasked with attacking up the valley along Route 5, and to the west Brigadier General Charles E. Hurdis' 6th Division blocked any Japanese trying to escape on Highway 4, US Sixth Army's General Walter Krueger wanted to seal the enemy’s potential escape by sea and box them in for elimination or their surrender. To do so, he elected to send in the 11th Airborne Division for an aerial deployment that would close the Cagayan Valley's northern end. General Krueger hoped this Aparri operation would eliminate one of Japan’s last standing armies in the Philippines and move the Allies one step closer to Tokyo.

As such, on June 21, 1945, General Walter Krueger ordered General Swing to prepare to drop a battalion combat team near Aparri on June 23. Codenamed: The Gypsy Task Force.

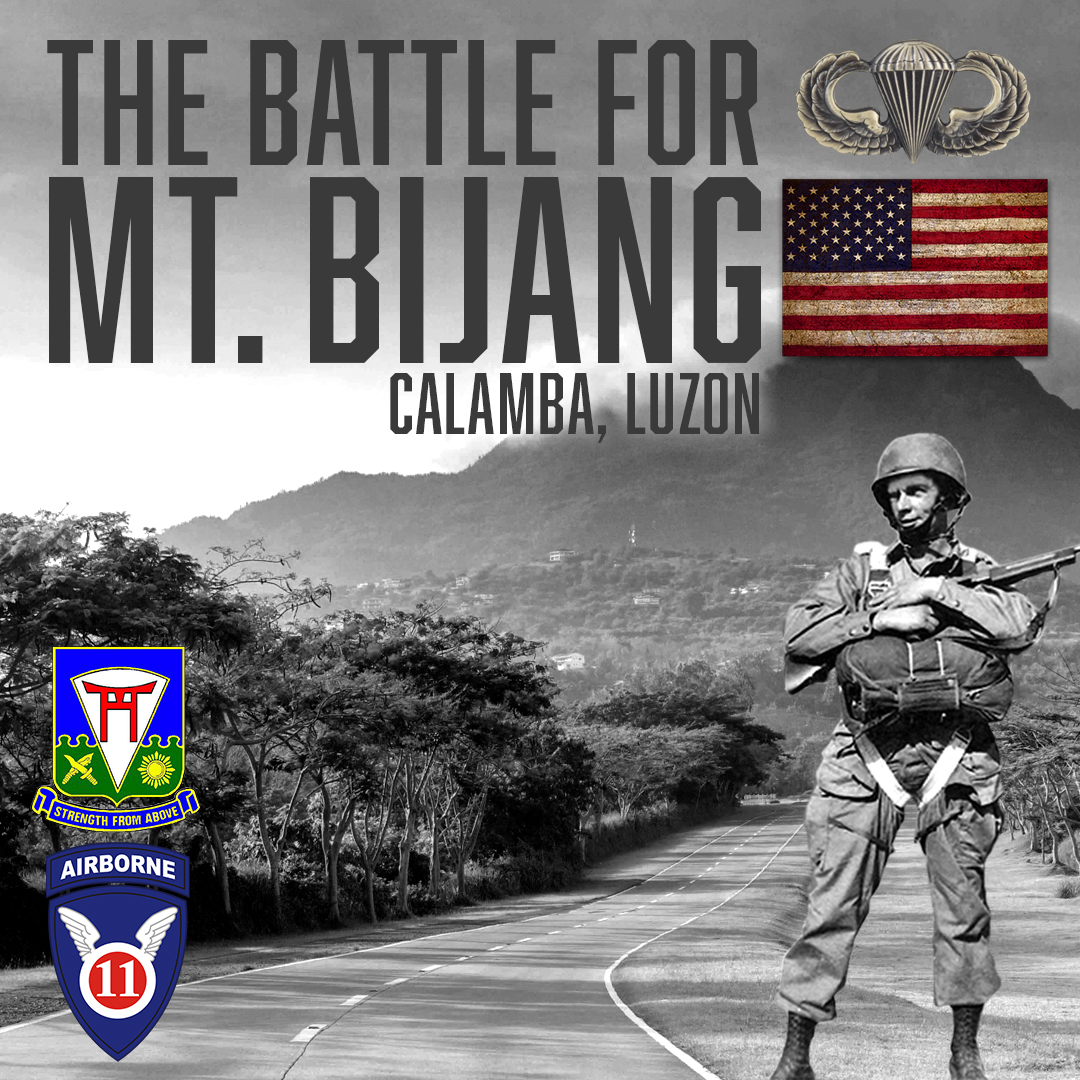

The Battle for Mt. Bijang is the story of one understrength parachute company in their fight to take and retain what their company commander called, "an insignificant piece of real estate" against an estimated 300 Japanese defenders. I have heard from the paratroopers who were there, including that company commander, and from my own grandfather,

The Battle for Mt. Bijang is the story of one understrength parachute company in their fight to take and retain what their company commander called, "an insignificant piece of real estate" against an estimated 300 Japanese defenders. I have heard from the paratroopers who were there, including that company commander, and from my own grandfather,  On August 12, 1945, one of the most tragic events in the history of the 11th Airborne Division occurred on what some would consider "an insignificant airbase" at Lipa, Batangas on Luzon, Philippine Archipelago. Outside of native Filipinos,

On August 12, 1945, one of the most tragic events in the history of the 11th Airborne Division occurred on what some would consider "an insignificant airbase" at Lipa, Batangas on Luzon, Philippine Archipelago. Outside of native Filipinos,