December 25, 1944

It was “a gray morning carved out of gray clay and shadowed by fog.”

It was “a gray morning carved out of gray clay and shadowed by fog.”

So penned T/4 Rodman "Rod" Serling of HQ1 a demolitions man who joined the several-miles-long column of bedraggled, trudging paratroopers coming down from Leyte’s hills. Rod and his comrades of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment had just completed 33 days of combat in those jungle-covered heights and mountains and as one of those troopers later declared, “After Leyte, Hell was a vacation.”

Hobbling on a wounded knee that would pain him for the rest of his life, Serling, the future creator of the famous television series “The Twilight Zone” did not feel like celebrating his twentieth birthday on “a God-forsaken mountaintop”. Rod noted, “(I)t was not the weather, it was the mood, I remember—the kind of mood that is the province of combat and is never fully understood by those who have not lived with the anguish of war.”

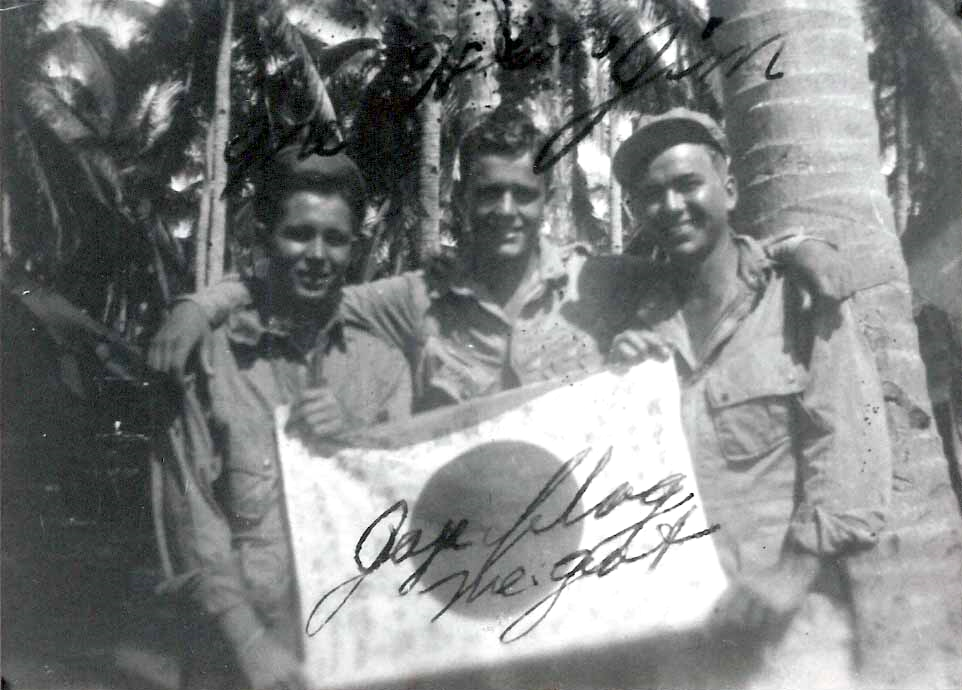

With Samurai swords and Japanese rifles jutting out of their packs, their last cigarettes safely tucked in cartridge belts, and hunching over from the weight of their equipment, the emaciated paratroopers, known as The Angels, trudged toward the beach with faces muted by the hells of war.

Cpl. Murray Marshall Hale of D Company recalled, “The march to the beach was literally a dream. Dreaming of a hospital, a shower, a meal and a bed – and not necessarily in that order.”

Nearly 250 men had to carry 2nd Battalion’s wounded in a column that stretched over half a mile, followed by 3rd Battalion, Regimental HQ and 1st Battalion who brought up the rear with Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen, the Angels’ beloved leader who had endured the island’s tribulations with them.

Haugen’s men had physically survived, yet words fail to fully describe the emotions of that survival, that odd blend of relief to be leaving a combat zone and the numbness that came from time in it. Their once-vigorous bodies were worn and atrophied by weeks of hunger, illness and exhaustion. Their formerly bright faces now had “tired inward-looking eyes reflecting nothing.” Their jungle ulcer-covered hands had inflicted death on the enemy and buried friends. Their revered jump boots were falling apart, their uniforms rotted, and their spirits raw. Even for Angels, war was Hell.

Haugen’s men had physically survived, yet words fail to fully describe the emotions of that survival, that odd blend of relief to be leaving a combat zone and the numbness that came from time in it. Their once-vigorous bodies were worn and atrophied by weeks of hunger, illness and exhaustion. Their formerly bright faces now had “tired inward-looking eyes reflecting nothing.” Their jungle ulcer-covered hands had inflicted death on the enemy and buried friends. Their revered jump boots were falling apart, their uniforms rotted, and their spirits raw. Even for Angels, war was Hell.

As 2nd Battalion continued their slog down the hills, someone at the front of the column stopped and whispered, “It’s Christmas…” Troopers around him grew quiet, which alerted those further back that something was going on. Whispers usually meant the enemy had been sighted, yet as simple Christmas greetings drifted down the line, the paratroopers were touched by emotion and became lost in their own thoughts of home, loved ones and the buddies who would see neither again.

Their quiet revere was soon broken by one trooper at the front of the column who began to sing.

“O come, all ye faithful

Joyful and triumphant

O come ye, o come ye to Bethlehem

Come and behold Him

Born the King of Angels!”

Other broken voices soon joined in.

“Oh, sing, choirs of angels

Sing in exultation;

— Sing, all ye citizens of heav’n above!

Glory to God,

Glory in the highest”

Sing choirs of Angels, indeed.

T/4 Rod Serling wrote, “I continued to lift my feet one after another, and suddenly I wasn’t aware of the cold rain or the mud. I gave no thought to the sickening ache deep inside the gut that had been with me for so many days. Someone had transformed the world… We sang as we led the wounded by the hand and carried the litters and looked back on the row of homemade crosses we left behind… It had come indeed—the Holy Day. The day of all days. It was Christmas.”

Re-reading Rod’s words of that holiday miracle on Christmas over sixty years later, my grandfather 1LT Andrew Carrico III of D Company softly noted with tears in his eyes, “I remember.” Grandpa and the 35 men of 1st Platoon had affected the regiment’s breakthrough to Ormoc Bay just three days earlier by performing a Rat’s Ass charge against emplaced Japanese position.

“I estimated we killed over 300 that day,” Grandpa recalled evenly. He then explained that while on Leyte the Angels were “Always hungry, always wet, always miserable. They were the worst conditions one could imagine.”

D Company’s Captain Stephen Edward Cavanaugh added, “We came out on the other side of the island a pretty well decimated regiment.” D Company itself left Bito Beach on Leyte’s eastern shore on November 23 with 117 men; twenty-one of Rusty’s men now lay dead in the mountains or were being carried down to Ormoc on poncho stretchers. The 511th itself was down to 60% strength and regimental surgeon Maj. Wallace Chambers estimated that the remaining men (many of whom were exceedingly ill with dysentery, dengue fever and/or malaria) needed six weeks to recover.

About 250 Filipinos, Army brass and 32nd Infantry Regiment troops turned out to watch the singing paratroopers, marching in broken jump boots and rotting fatigues with oozing jungle sores covering their bodies. In spite of their ragged appearance, the 511th PIR entered the encampment with power and How Company’s Pfc. Richard “Dick” Keith later wrote, “The glue that held (the regiment) together was the strength of character of the men; their cohesiveness, discipline, and their love and respect for each other. Add to this the word courage; the ability to go out day after day, attacking the enemy, fatigued but strengthened in their resolve to defeat the enemy, and eventually get on with their lives.”

Regimental Sergeant Major Fredrick Thomas declared with pride, “(The) 511th withstood combat experiences in the mountains that would have ruined an ordinary army unit.”

Cpt. Cavanaugh added, “This was a professional, well- trained regiment with a commanding officer (Colonel Orin Haugen) who set an example for all of us to follow.”

D Company’s youngest member, seventeen-year-old Pfc. Billy Pettit declared, “I feel privileged to have had the opportunity to serve with them.”

The regiment’s wounded were passed to the Medical Corps who loaded the men onto landing craft for a short trip down the coast to Baybay where an old church had been converted into a hospital. Most were later loaded onto a hospital ship bound for Hollandia, New Guinea.

After being issued new fatigues and mosquito-proof jungle hammocks, the smelly, dirty and tired Angels moved to Ormoc’s beach for a warm-water swim. Splashing into the surf, the naked young men scrubbed their mud-, sweat- and repellent-covered bodies and felt skin slough off their feet.

HQ3’s Pfc. Robert LeRoy described the mood, saying, “We were happy… What a thrill it was to drop my packs and weapons, take off my boots and worn out socks, then slide my aching feet into the warm ocean sand.”

Gen. MacArthur’s Christmas Eve message was distributed throughout the theater and the Angels were pleased to find themselves finally mentioned: “Operating in the central mountain regions southeast of Ormoc, the 11th Airborne has been waging aggressive warfare along a wide sector. The Division has annihilated all resistance within the area.”

Maj. Edward Flannigan of the 457th PFAB noted, “Other units had maintained, after actual attempts, that the central ranges were impassible and military operations could not be conducted in the area. We proved otherwise.”

“Reports say we killed 5,760 Japanese on Leyte,” Grandpa added to MacArthur’s use of annihilated. “Altogether our platoon (of thirty-five men) probably killed 500 between November 22, when we went into the mountains, and December 25, when we came out.”

Doing the math, 1st Platoon had an 83-to-1 kill ratio with the division’s being 45-to-1. For their actions on Leyte, the 11th Airborne received 96 Silver Stars, 6 Soldier’s Medals, 90 Air Medals and 423 Bronze Stars. For his part in the Rat’s Ass Charge, Grandpa was awarded one of the later.

To help the 11th Airborne Division celebrate Christmas, the 408th Airborne Quartermaster Company acquired ten thousand turkey rations. The Angels also distributed Red Cross packages and division chaplains held holiday services before the highly anticipated chow call was sounded.

“(Our Division commander) General (Joseph) Swing promised us the best Christmas dinner we had ever eaten if we ran the Japs off Leyte,” Grandpa/1LT Carrico remembered with a laugh. “He kept his word. We had turkey with all the trimmings and pineapple ice cream.”

Cpl. William R. Walter of D Company added, “We had only been supplied, 11 days out of 30 and were so hungry we gobbled up everything.”

It was the first true hot meal most had eaten in seven months and twenty minutes later, paratroopers rushed for the beaches or slit trenches. Grandpa noted, “Everybody got sick. Our stomachs couldn’t handle it because we’d gone so long without good food.”

Though weakened, Grandpa wrote home to his wife, Lois, “I have been in combat and spent about thirty of the toughest days of my life. I am fine except for two sore feet (you know the infantry) and could really go for a rest. I know you’ve been worried about me and I hope it didn’t spoil your Christmas. Every time I prayed, which was plenty, I asked God to tell you I was all right. I love you. Andy.”

Just down the beach, Major-General Joseph May Swing had lunch with Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger, commander of the new U.S. Eighth Army to discuss what role the 11th Airborne Division would play in the future invasion of southern Luzon. Despite their losses, Eichelberger wanted the Angels for his fight to liberate Manila.

Yet even as they dined, many of Swing’s men, especially in the 511th PIR, lay on their cots, too sick to move. The streets and beaches were lined with “evidence” of those who were too weak to make it to the latrines and the medical staff kept busy day and night with their care. By every right, the Angels were in no shape to go another round, yet that is exactly what they would be asked to do. Eichelberger, the former West Point superintendent, knew what was waiting on Luzon and believed that even after their brutal time in the mountains, Gen. Swing’s men could be counted on to get the job done.

That “job” had come from Gen. Douglas MacArthur himself who wanted Eichelberger to “undertake a daring expedition against Manila with a small mobile force using tactics that would have delighted Jeb Stuart.” With the right transportation, the Angels’ nimble airborne forces excelled at such operations so on January 22, Gen. Eichelberger issued Field Order No. 17 which read:

11th A/B will land one regimental combat team on X-day at H-hour in the Nasugbu area, seize and defend a beachhead; 511th Parachute Regimental Combat team will be prepared to move by air from Leyte and Mindoro bases, land by parachute on Tagaytay Ridge, effect a junction with the force of the 11th A/B Div moving inland from Nasugbu; the 11th A/B Div, reinforced, after assembling on Tagaytay Ridge will be prepared for further action to the north and east as directed by Commanding General, Eighth Army.

Eichelberger wanted Swing’s division to land on January 31, which only gave the Angels six days to prepare. Numerous lectures were held around sand tables which represented the areas between Nasugbu, Batangas and Manila. The 511th PIR’s paratroopers packed supplies, cleaned their weapons and wrote final letters home.

The war for Luzon was raging and the 11th Airborne was going to fight it.

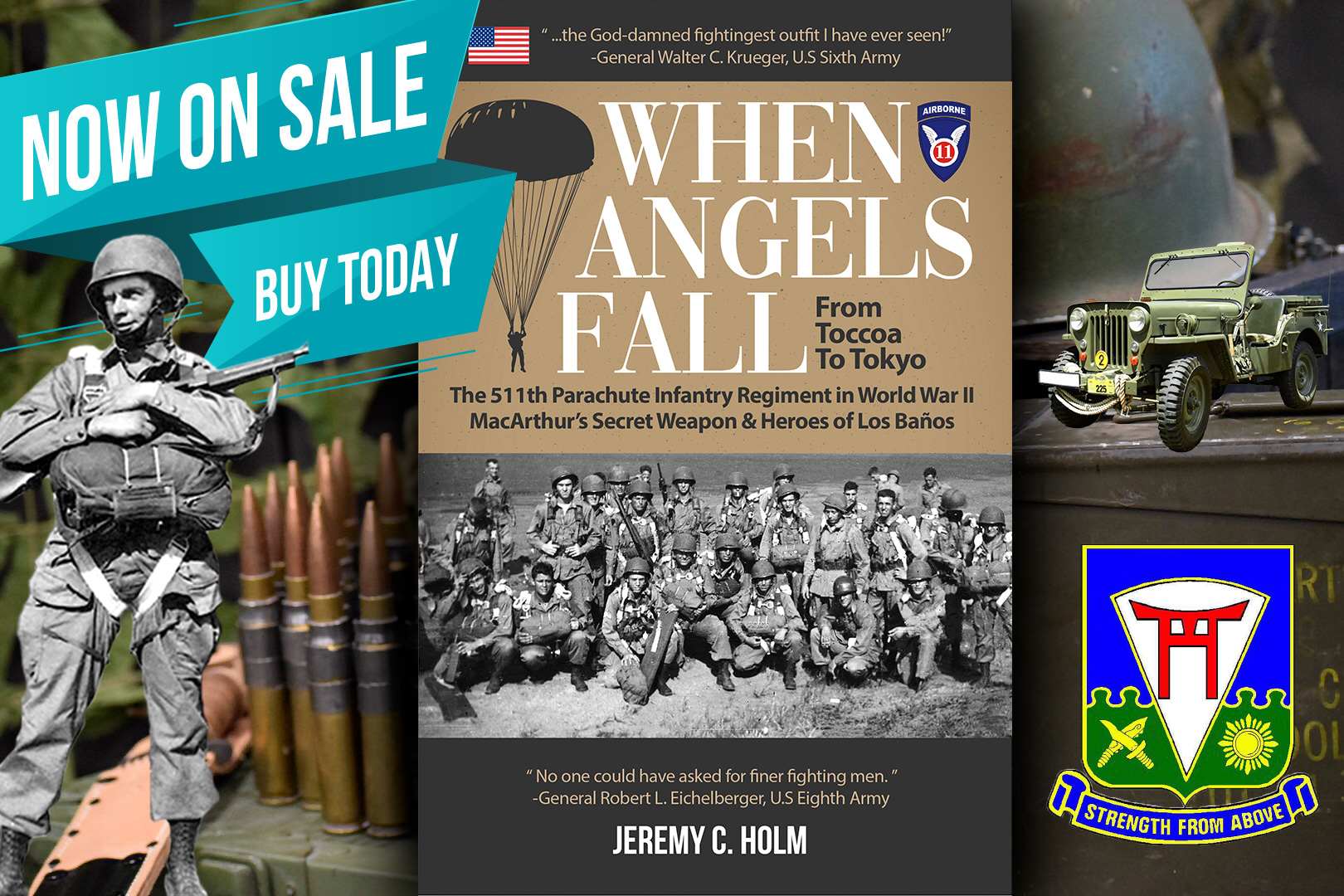

To learn more about this historic regiment and the intrepid men who fought in it, you can order Jeremy C. Holm's new book, WHEN ANGELS FALL: From Toccoa to Tokyo, The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II by visiting our online store or purchasing a copy wherever books are sold.