For years now I have been reading and listening to articles and podcasts mistakenly claiming that Operation Varsity (part of Operation Plunder) was the last airborne operation of World War II. While Varsity was indeed an enormous campaign that involved over 16,000 paratroopers and thousands of aircraft, it was not THE last airborne operation of the war, though in can correctly be called the last one held on such a massive scale (Varsity was the largest single-day/single-location airborne deployment in history).

For years now I have been reading and listening to articles and podcasts mistakenly claiming that Operation Varsity (part of Operation Plunder) was the last airborne operation of World War II. While Varsity was indeed an enormous campaign that involved over 16,000 paratroopers and thousands of aircraft, it was not THE last airborne operation of the war, though in can correctly be called the last one held on such a massive scale (Varsity was the largest single-day/single-location airborne deployment in history).

So, if that is the case, what WAS the last airborne operation of World War II? Answer: The 11th Airborne Division's Gypsy Task Force.

Operation Varsity kicked off March 24, 1945 in Wesel, Germany whereas the Angels' landings at Aparri, Luzon, P.I. occurred on June 23, 1945, almost three months to the day after Varsity. For decades, members of the 11th Airborne Division have heard erroneous reports stating that their brothers in the 17th Airborne Division were honored with "making the final jump of the war", but that credit actually belongs to the Angels. In addition, the 11th Airborne was scheduled to drop on Japan during the anticipated Operation Olympic in late 1945, a campaign that was thankfully aborted due to Japan's surrender. This cancelled drop would have put the Angels' last airborne deployment even later than Varsity, likely around November of 1945. But let's dig in to the actual LAST airborne deployment of the war, the Gypsy Task Force.

Origins of The Gypsy Task Force

While Nazi Germany officially surrendered to the Allies on May 7, 1945, the 11th Airborne Division was still busy fighting an indignant Imperial Japan in the Philippines. Yes, there were some in Japan's governing bodies who were leaning towards surrender as victory was becomming an increasingly hopeless prospect, Imperial forces were still fighting bloody battles across the Pacific. It is so easy to forget that while countries around the world were celebrating VE Day on May 8, 1945, Allied forces fighting in the Pacific Theater were still fighting or getting ready to launch the bloody campaigns to retake Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Luzon and Mindano. While shouts of "Peace! Peace! Its over!" rang throughout the streets of Europe, the Pacific war went on and continued to cost the Allies over one-hundred-thousand casualties.

In May of 1945, AFTER VE Day, the veteran 11th Airborne Division was still heavily involved in the battle to liberate the island of Luzon in the Philippine Archipelago. Under the command of Major General Joseph May Swing, the Angels had fought their way from Nasugbu on the island's west coast, up towards Tagaytay Ridge where the division's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment made a parachute drop on February 3, then the division pushed north to participate in the brutal Battle for Manila. For a complete description of this campaign, please consider purchasing a copy of our book on the 11th Airborne, WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II. The Angels suffered heavy casualties in the fight to retake the city and then in their ensuing operations to retake the mountains and cities of Luzon's southern and southeastern sectors.

In May of 1945, AFTER VE Day, the veteran 11th Airborne Division was still heavily involved in the battle to liberate the island of Luzon in the Philippine Archipelago. Under the command of Major General Joseph May Swing, the Angels had fought their way from Nasugbu on the island's west coast, up towards Tagaytay Ridge where the division's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment made a parachute drop on February 3, then the division pushed north to participate in the brutal Battle for Manila. For a complete description of this campaign, please consider purchasing a copy of our book on the 11th Airborne, WHEN ANGELS FALL: FROM TOCCOA TO TOKYO, THE 511TH PARACHUTE INFANTRY REGIMENT IN WORLD WAR II. The Angels suffered heavy casualties in the fight to retake the city and then in their ensuing operations to retake the mountains and cities of Luzon's southern and southeastern sectors.

Things slowed down a little for a few weeks in early June when the Angels were given some time to rest and recuperate, plus integrate badly needed replacements. The division as a whole suffered 18% casualties, higher than most infantry divisions in the PTO; some of General Swing's companies had endured 70% casualties. Their short rest, however, would not last. The Japanese were still waiting in defensive pockets spread throughout Luzon. One of those pockets was centralized in northern Luzon and there was some concern was that the remnants of Japan's 150,000-man "Shobu Group", what was left of General Tomoyuki Yamashita's 14th Army, would make its way north towards the coast where perhaps the Imperial Navy could effect some sort of Dunkirk-like rescue.

As it stood in early June of 1945, Yamashita (seen in the photo to the right) had already begun enacting the abandonment of the Cagayan Valley itself with a withdrawal into the Cordillera Central. The general planned to spread his forces throughout three defensive perimeters around Luzon's fertile Cagayan Valley which, like an inverted triangle, was encircled on the north by the Babuyan Channel, on the west by the impressive Cordillera Central hills and to the east by the Sierra Madre mountain range. Nicknamed the "Tiger of Malaya" and "The Beast of Bataan", Yamashita had deployed the Shobu Group well around the large valley's perimeter that was a natural stronghold full of gorges and razor-backed ridges and mountain tops. To give his men time to gather and stockpile resources from the valley itself, Yamashita was coordinating a slow "war of attrition" rather than decisive actions with forces that consisted of the 19th Division, the bulk of the 23rd Division, and elements of three others: the 103rd and 10th Divisions and the 2nd Tank Division. Both sides knew that the longer the Japanese had to prepare their defenses, the more casualties it would take to reclaim the Cagayan Valley and the surrounding mountains. It would also allow the enemy to stockpile provisions taken from the productive area since the US Navy had cut off all amphibious enemy resupply (although, again, a Dunkirk-like rescue was a concern, though highly unlikely).

As it stood in early June of 1945, Yamashita (seen in the photo to the right) had already begun enacting the abandonment of the Cagayan Valley itself with a withdrawal into the Cordillera Central. The general planned to spread his forces throughout three defensive perimeters around Luzon's fertile Cagayan Valley which, like an inverted triangle, was encircled on the north by the Babuyan Channel, on the west by the impressive Cordillera Central hills and to the east by the Sierra Madre mountain range. Nicknamed the "Tiger of Malaya" and "The Beast of Bataan", Yamashita had deployed the Shobu Group well around the large valley's perimeter that was a natural stronghold full of gorges and razor-backed ridges and mountain tops. To give his men time to gather and stockpile resources from the valley itself, Yamashita was coordinating a slow "war of attrition" rather than decisive actions with forces that consisted of the 19th Division, the bulk of the 23rd Division, and elements of three others: the 103rd and 10th Divisions and the 2nd Tank Division. Both sides knew that the longer the Japanese had to prepare their defenses, the more casualties it would take to reclaim the Cagayan Valley and the surrounding mountains. It would also allow the enemy to stockpile provisions taken from the productive area since the US Navy had cut off all amphibious enemy resupply (although, again, a Dunkirk-like rescue was a concern, though highly unlikely).

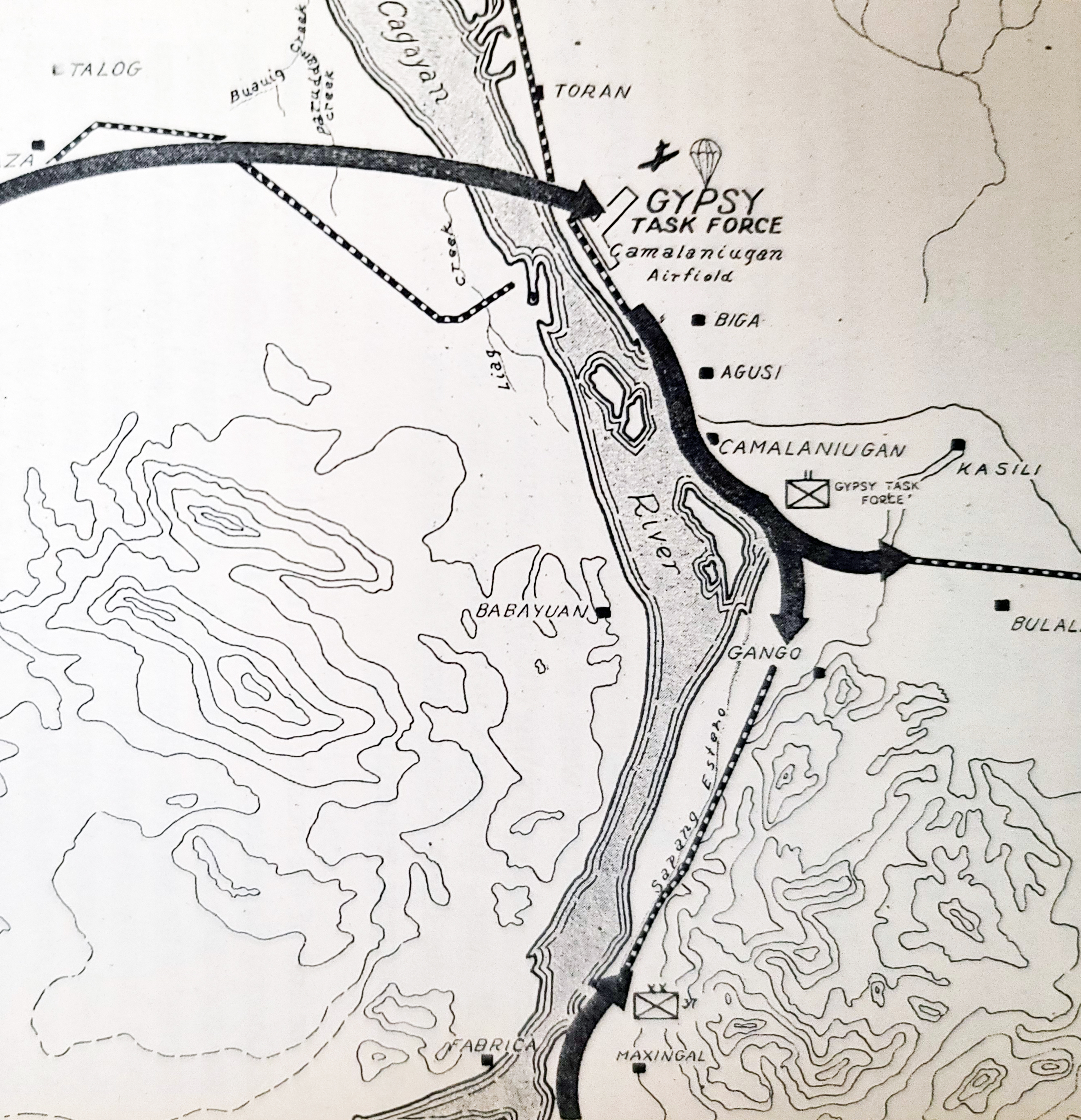

And while the Ohio National Guard’s 37th Infantry, the “Ohio/Buckeye Division”, was tasked with attacking up the valley along Route 5, and to the west Brigadier General Charles E. Hurdis' 6th Division blocked any Japanese trying to escape on Highway 4, US Sixth Army's General Walter Krueger wanted to seal the enemy’s potential escape by sea and box them in for elimination or their surrender. To do so, he elected to send in the 11th Airborne Division for an aerial deployment that would close the Cagayan Valley's northern end. General Krueger hoped this Aparri operation would eliminate one of Japan’s last standing armies in the Philippines and move the Allies one step closer to Tokyo.

As such, on June 21, 1945, General Walter Krueger ordered General Swing to prepare to drop a battalion combat team near Aparri on June 23. Codenamed: The Gypsy Task Force.

G.O.B.I. Goat Rope

Hindsight is, of course, always 20/20 and the 11th Airborne Division's involvement in the Cagayan Valley campaign was felt by some Angels (in 1945 and in the years after) to be a waste of time and energies. Not that the Angels were unwilling to fight; General Krueger himself called them "the God-damned fightingest outfit I have ever seen!" and an after-action report noted that, "Morale was excellent during the entire operation."

No, the Angels' desire to fight was never in question, and they knew Aparri was the perfect vertical envelopment mission for the 511th PIR. But by the time the battle-worn 11th Airborne was officially tasked with dropping on Aparri, the Angels knew that other Sixth Army units had already cleared vast stretches of southern Cagayan Valley, as had local Filipino guerilla groups. In fact, on the very day the 11th AB was given orders to drop on Aparri, the 33rd Infantry Division’s 800-man Task Force Connolly under Major Robert V. Connolly entered Aparri itself virtually unopposed (although some reports estimated there were 4,000 Japanese in the northern Cayagan Valley areas of Dugo-Pattasbinag-La-Lo).

Even so, General Krueger would later declare that the "seizure of Aparri without opposition by elements of the Connolly Task Force on 21 June 1945, together with the almost unopposed advance of the 37th Division, indicated clearly that the time had come for mounting the airborne troops to block the enemy's retreat in the Cagayan Valley."

In the decades since, countless 11th Airborne troopers have wondered just who they went to Aparri to block exactly? General Yamashita's plan to establish three defensive lines throughout the Cagayan Valley had fallen apart and with his HQ set up at Kiangan in June of 1945, he issued new orders telling his forces to withdraw into a last-stand area that he would set up along the inhospitable valley of the Asin River, between Routes 4 and 11. Krueger wanted the Angels to land at Aparri and push south to block any enemy forces heading north, but virtually all of Yamashita's remaining units were already heading south and west.

No wonder Aparri derogatorily became the Angels' "GOBI", or some "General Officer's Bright Idea". Whether they felt that general officer was General Krueger or Swing was never clarified, although emotions leaned more towards Krueger. The General's US Sixth Army was scheduled to hand over operational control to General Robert Eichelberger's Eighth Army on July 1, 1945 and the Aparri drop was viewed by some as a way for Krueger to "finish the race" before he had to pass the baton to Eichelberger.

Captain Stephen Cavanaugh of the 511th PIR felt the responsibility lay a little higher, saying, "I… felt the operation to be more of a newspaper stunt by General Macarthur’s Headquarters more than anything else."

Wherever the "blame" (or credit) lies, word of the new Aparri mission came to the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment on June 21 where CPT Cavanaugh was settling into his new role as 1st Battalion’s Executive Officer. His battalion commander, West Point-graduate and the regiment’s former S-3 Major Fredrick J. Wright, was an old friend. The cordial, mutual respect was apparent between the two veterans as they reviewed plans for the Aparri campaign while the 511th was encamped near Lipa airstrip which was selected for staging.

Wherever the "blame" (or credit) lies, word of the new Aparri mission came to the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment on June 21 where CPT Cavanaugh was settling into his new role as 1st Battalion’s Executive Officer. His battalion commander, West Point-graduate and the regiment’s former S-3 Major Fredrick J. Wright, was an old friend. The cordial, mutual respect was apparent between the two veterans as they reviewed plans for the Aparri campaign while the 511th was encamped near Lipa airstrip which was selected for staging.

In early briefings, Cavanaugh and Wright learned that their understrength 1st Battalion would form the main bulk of the Gypsy Task Force which General Swing ordered be comprised of "all Camp Mackall veterans" including the 511th PIR's 1st Battalion, to which the 511th PIR's Colonel Edward Lahti added 3rd Battalion's "G" and "I" companies attached. Supporting units attached were: Battery "C" of the 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion, a composite platoon from the 127th Airborne Engineer Battalion, the 221st Medical's 2nd Platoon, 511th Signal Company, members from the Language Detachment, the CIC (Counter Intelligence), and the 11th Parachute Maintenance Company.

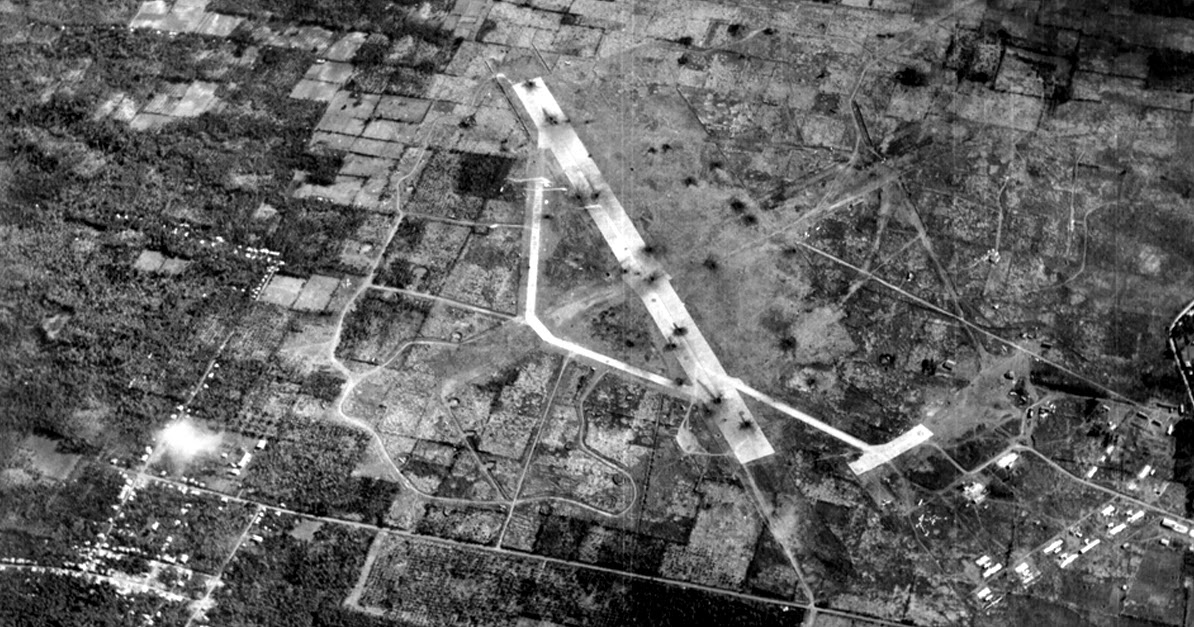

The Gypsy Task Force would drop 507 paratroopers at the Camalaniugan Airport, followed by one CG-13 and six towed Waco CG-4 gliders carrying the remaining troops, along with heavy weapons plus flame throwers, radios and Jeeps. Once assembled, TF-Gypsy’s 1,030 men would link up with Filipino guerillas and push south to connect with the 37th Infantry Division, eliminating any enemy forces caught in-between.

During briefings, Intelligence warned that enemy strength near the Drop Zone around the Camalaniugan Airport was unknown and that the Japanese would likely shell the fields from nearby hills with at least one battery of 75mm howitzers, one battery of 105s and four 15cm mortars. Clearing the area with haste was emphasized, although Allied fighter-bombers of the Fifth Air Force would drop smoke to the east and south to conceal the Aparri DZ which was selected because it was large enough for an aerial drop and would serve for resupply and casualty evacuation.

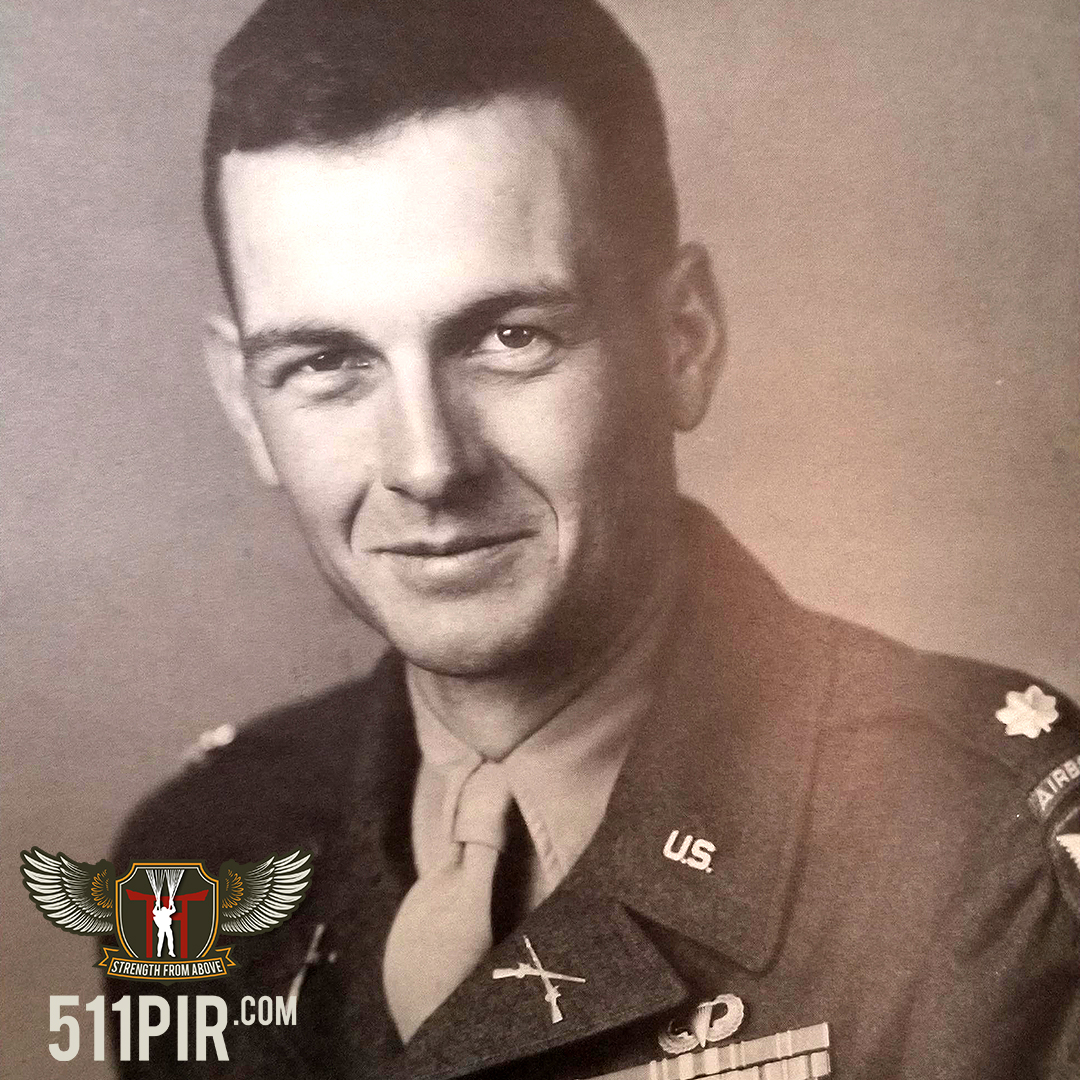

And while General Walter Krueger initially baulked due to his age, General Swing and Colonel Lahti gave command of the Gypsy Task Force to the twenty-six year old now-Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Burgess (photo right). Burgess, the 511th's Regimental Executive Officer, was famous for participating so effectively in the division's raid on the Los Baños internment camp (the 511th PIR's CO Colonel Lahti would remain behind to command the reserve force). When General Swing notified LTC Burgess of his promotion, he gave Hank the same oak leaves he had worn as a Lieutenant Colonel, a memento Burgess cherished until his death in 1995 in Sheridan, Wyoming.

And while General Walter Krueger initially baulked due to his age, General Swing and Colonel Lahti gave command of the Gypsy Task Force to the twenty-six year old now-Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Burgess (photo right). Burgess, the 511th's Regimental Executive Officer, was famous for participating so effectively in the division's raid on the Los Baños internment camp (the 511th PIR's CO Colonel Lahti would remain behind to command the reserve force). When General Swing notified LTC Burgess of his promotion, he gave Hank the same oak leaves he had worn as a Lieutenant Colonel, a memento Burgess cherished until his death in 1995 in Sheridan, Wyoming.

Recon & Preparations

On June 20 (D+141 for the Angels' Luzon campaign), Captain Stephen Cavanaugh boarded a B-25 bomber alongside LTC Burgess and 1st Battalion’s Major Wright for a reconnaissance flight over the Camalaniugan drop zone near the Cagayan River. As the craft approached Aparri and dropped to a few hundred feet in altitude, risking enemy fire, Captain Cavanaugh crawled to the tail-gunner’s position. Looking out through the gunner's plexiglass bubble, the well-trained paratrooper assessed the spacious fields which appeared to be a large expanse of abandoned and overgrown rice paddies. In the distance, Rusty studied the group of low-lying hills that Intelligence estimated were occupied by Japanese artillery and given their proximity to the DZ, 1st Battalion’s XO could see why G2 was concerned.

Declaring the DZ acceptable, albeit potentially risky, the bomber and its Angels' cargo returned to base. General Swing, Colonel Lahti and LTC Burgess then made their own recon flight and after giving their approval, on June 21 (D+142) a group of the 511th’s pathfinders dropped near the Camalaniugan Airfield where they would pop green colored smoke grenades when the task force’s jump craft approached.

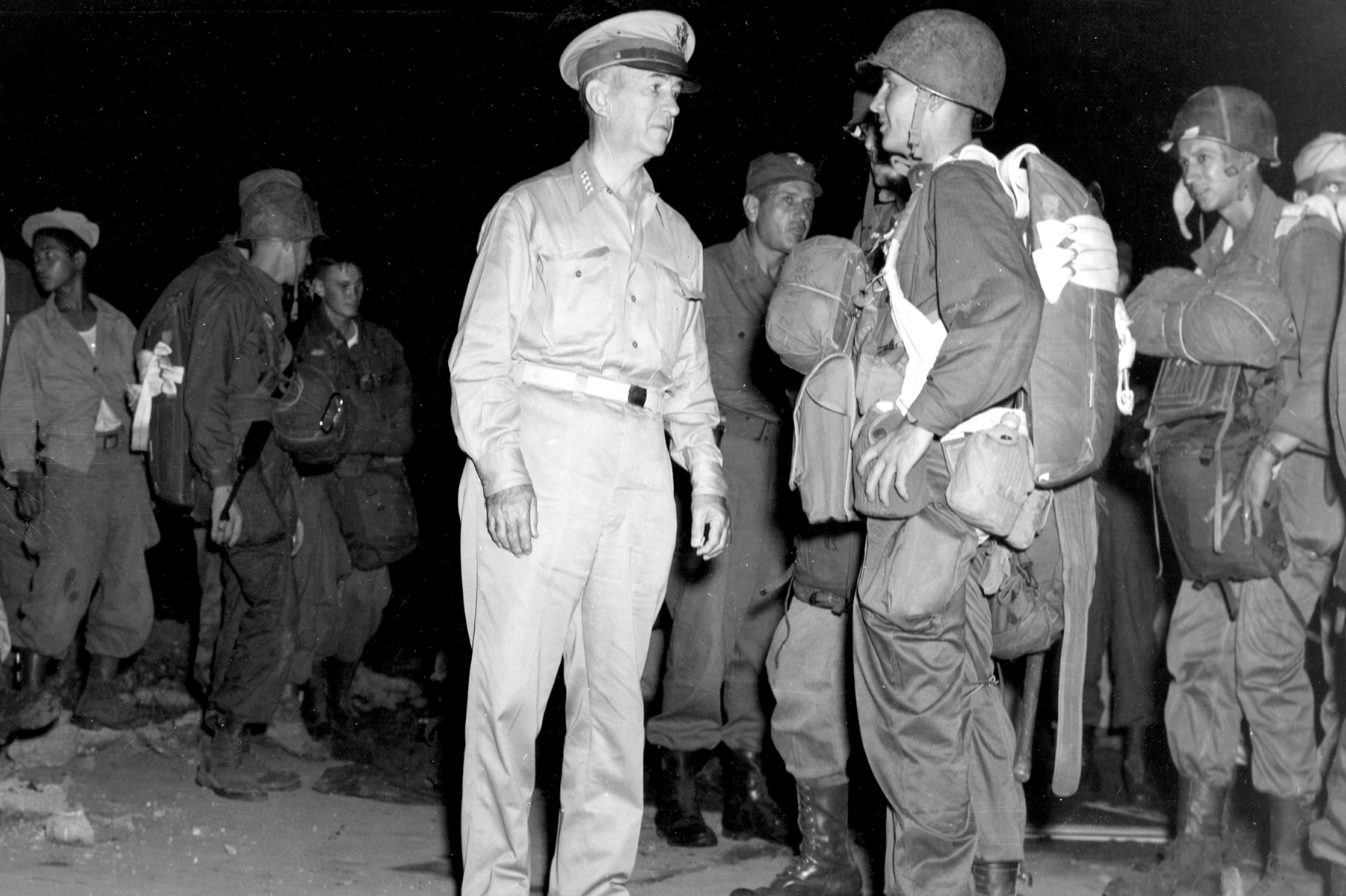

The original date for the drop was June 25, but due to the 37th Infantry’s rapid advances the operation was moved to June 23 (D+143). This gave the Angels only thirty-six hours to prepare and on June 22 (D+142) General Krueger arrived at the Lipa airstrip to review their efforts along with General Swing. Colonel Henry Burgess then reported and Krueger asked Hank how old he was.

"Twenty-six," Burgess replied. Surprised, Krueger asked General Swing if he didn't have an older officer to lead the operation to which Swing replied, "Yes, Colonel Lahti, who is thirty-one, but in the event the Gypsy Task Force has trouble, Lahti would take the rest of the regiment and reinforce the troops."

Krueger then eyed Burgess and asked if he had attended, "The Academy." Knowing the general meant the West Point, Henry replied that he had not, but he had received a Harvard education. Both generals seemed to get a kick out that.

Trusting Swing's and Colonel Lahti's judgement on Burgess' capabilities, Krueger dropped all objections.

At about 0300 on June 23, 1945, the Angels made their way through the messes for a "Condemned Men's" breakfast of steak and eggs which for some was the first real food that they had eaten since landing on Tagaytay Ridge four months earlier. One trooper, however, was quick to point out that the "Battle Breakfast" "wasn't as good as it sounds."

At about 0300 on June 23, 1945, the Angels made their way through the messes for a "Condemned Men's" breakfast of steak and eggs which for some was the first real food that they had eaten since landing on Tagaytay Ridge four months earlier. One trooper, however, was quick to point out that the "Battle Breakfast" "wasn't as good as it sounds."

Nor was General Walter Krueger’s "pregame speech" given to the 511th PIR’s gathered paratroopers. While the men respected Krueger, as we have established, there was little enthusiasm for the operation. The 33rd Infantry Division’s Task Force Connolly had already entered Aparri itself virtually unopposed from the west and, after clearing any Japanese from the area, would meet the Angels on the ground, as would Colonel Russell W. Volckmann's 11th Infantry Division (USAFIP-NL) which kept busy filling shell-holes around drop zone.

With all these developments, plus the 37th Infantry Division's continued elimination of Japan’s Shobu Group, the Angels questioned the necessity of their labors over their breakfast.

After eating, Captain Stephen Cavanaugh and the 511th PIR's 1st Battalion troopers (planes 2-32), along with G and I Companies of 2nd and 3rd Battalions (planes 37, 39-43), trucked to the waiting aircraft at around 0430 under the watchful eyes of General Krueger. Colonel John Lackey of the 317th Troop Carrier Group had rushed to gather the necessary 54 C-47s, 14 C-46s and the seven Waco gliders which would take flight via the “snatch pickup” method, whereby C-47s flew in at 15 feet and used special tail hooks to grab the towropes. This zero-to-120 mph acceleration sometimes left “glider-riders” with whiplash and the 511th’s paratroopers were happy to avoid it at all costs.

Departures & Flights to the DZ

After strapping into their chutes and positioning their gear, including 4 K-Rations and 1 D-bar, the Angels waddled towards their planes between 0430-0530 and settled onto canvas seats. Conversations were minimal as they imagined the possible fighting ahead and some troopers smoked, careful to keep ashes away from their kits while they sat sweating in the morning heat.

After strapping into their chutes and positioning their gear, including 4 K-Rations and 1 D-bar, the Angels waddled towards their planes between 0430-0530 and settled onto canvas seats. Conversations were minimal as they imagined the possible fighting ahead and some troopers smoked, careful to keep ashes away from their kits while they sat sweating in the morning heat.

Ironically, the enemy had used the same Lipa airstrip to launch their failed December 6, 1944 airborne assault against the Angels on Leyte at the San Pablo and Buri Airstrips. The 511th’s paratroopers were told by local Filipinos that the Japanese had taken the laborers who originally repaired and expanded the airfield and bayoneted them before shoving them off a cliff, alive.

About fifteen minutes after boarding, the paratroopers were surprised to see General Swing and his staff, along with Winston Churchill’s personal representative General Charles Gairdner, walking around the tarmac to converse with the waiting Angels in their craft (Colonel Lahti was also onsite). While the men generally appreciated Swing’s well-wishes, at least one HQ1-511 paratrooper did not.

"I remember quite well that in my aircraft his greeting was met by someone replying out of the darkness with a remark that was not publishable," Captain Stephen Cavanaugh noted with a smile. "I’m sure it took (the general) somewhat by surprise. Some of the men of the 511th were not impressed by Swing’s concern."

Perhaps their unenthusiastic attitudes stemmed from the fact that Swing admitted right there in the plane that the operation was not really necessary as the Japanese were already well-contained, confirming their concerns that the drop was superfluous. Nevertheless, the jump was on and the general left the plane with a "Tally ho" as the Gypsy Task Force’s aircraft started their engines at 0605. The flights rendezvoused at 0630 then headed north and approached the DZ at about 0900 where Colonel John Lackey in the lead plane noticed the 11th Airborne's pathfinders popping green smoke. Minutes later at 700-600 feet the jump masters herded their sticks out the doors just after sunrise which provided the Angels a rather scenic horizon to watch during descent.

Their landings, however, were less pleasant, as viewed by General Swing, Lieutenant-Colonel Douglas Quandt (Swing's G-3) and Colonel Lahti who flew in another B-25 to watch the drops (the other reason the three officers were at the Lipa airstrip that morning).

"The ground upon which we landed had been baked by the sun and was as hard as concrete," Captain Cavanaugh recalled, a detail that had been impossible to ascertain during the earlier recon flights. As a result, the Task Force suffered two fatalities from chute malfunctions and over seventy jump injuries, 7% of their strength, when 25 MPH heavy winds blew troopers into trees or other uneven features on the DZ (15 MPH was considered the maximum safe velocity). And while no enemy artillery fired on them (patrols soon found there were none on the heights), some Angels experienced moments of panic when the seven Waco gliders floated in.

"The ground upon which we landed had been baked by the sun and was as hard as concrete," Captain Cavanaugh recalled, a detail that had been impossible to ascertain during the earlier recon flights. As a result, the Task Force suffered two fatalities from chute malfunctions and over seventy jump injuries, 7% of their strength, when 25 MPH heavy winds blew troopers into trees or other uneven features on the DZ (15 MPH was considered the maximum safe velocity). And while no enemy artillery fired on them (patrols soon found there were none on the heights), some Angels experienced moments of panic when the seven Waco gliders floated in.

"The gliders landed directly upon our DZ," Rusty explained. "We assembled quickly (at 0935) without any enemy contact and immediately began moving south (at 1010)." Task Force Connolly and the 11th Infantry Division would both remain in and around Aparri while the Angels began their march.

Traveling with the column were three combat photographers of the Newsreel Unit 0 Signal Corps Team who would provide photos and footage of America’s final combat air assault operation of the war, not that anyone knew it was the last. After their jump casualties were evacuated to the 24th Portable Surgical Hospital at Ballesteros, Captain Cavanaugh and 1st Battalion continued south for about an hour when they were stopped in their tracks. Rusty said, "A spanking clean, 2nd lieutenant in a starched fatigue uniform stepped out from the wood line and introduced himself as a U.S. Army member of a Philippine guerrilla unit."

The lieutenant informed the surprised paratroopers that he had been sent by Colonel Donald D. Blackburn and that the Filipino 11th Infantry Regiment already had the area secured. Blackburn had served with the Philippine Army before Japan took Corregidor in 1942 and after escaping the invading enemy helped organize guerilla forces by serving as commander of such units on Luzon until May 1943 when he was named Commander of the Philippine’s 11th Infantry Regiment until the war’s end. Blackburn would later make history as the first Chief of SOG during the Vietnam War, a position he would later ask then-Colonel Stephen Cavanaugh to take over from 1968-1970.

While Cavanaugh and 1st Battalion's paratroopers moved off the road and formed a perimeter, Rusty and his CO Major Fredrick Wright accompanied the American lieutenant through the jungle to Blackburn’s well-established camp where the colonel sat with the Angels to discuss Task Force Gypsy’s mission. Blackburn let the two veteran paratroopers know that the Japanese had already withdrawn into the Sierra Madre mountains to the east and he was surprised the operation had even been ordered.

While Cavanaugh and 1st Battalion's paratroopers moved off the road and formed a perimeter, Rusty and his CO Major Fredrick Wright accompanied the American lieutenant through the jungle to Blackburn’s well-established camp where the colonel sat with the Angels to discuss Task Force Gypsy’s mission. Blackburn let the two veteran paratroopers know that the Japanese had already withdrawn into the Sierra Madre mountains to the east and he was surprised the operation had even been ordered.

“In all honesty,” said Rusty, “Wright and I agreed (with Blackburn) and felt the operation to be more of a newspaper stunt by General Macarthur’s Headquarters more than anything else.” Taking their leave, Cavanaugh and Wright returned to 1st Battalion and continued south along the road another four miles before digging in for the evening just south of the Duman River. Although Colonel Blackburn had reported that the area was clear of enemy forces, old habits died hard.

"The mosquitoes were the only opposition we had encountered," Rusty remarked dryly, although that day four men from G Company ("Gizzard Red") had been wounded by friendly fire.

Surprisingly the Angels were hailed again by a Philippine Army officer who bid Cavanaugh and Major Wright accompany him back to his base, an invitation that after some debate they decided to accept. Leaving the battalion in good order, the officers followed their new guide through the darkness to the wide Cagayan River which they crossed using bancas. Reaching the far shore, the guide led them through the jungle for another half-hour before reaching his camp. As a testament to the area’s security, the Filipinos had their bivouac well-lit and the two Angels were warmly welcomed to the headquarters of the Philippine 11th Infantry Division itself.

"If nothing else the Philippine 11th Infantry was living a life of style and seemed oblivious to any enemy threat," Rusty noted. Although Colonel Blackburn’s subordinates had confirmed their status as friendlies, Cavanaugh’s and Wright’s initial reservations stemmed from the fact that despite nine months of combat on Luzon, neither had heard of this particular Filipino division before (likely because the unit had been organized and supplied by the U.S. military after the Angel’s landings on Leyte in October).

"If nothing else the Philippine 11th Infantry was living a life of style and seemed oblivious to any enemy threat," Rusty noted. Although Colonel Blackburn’s subordinates had confirmed their status as friendlies, Cavanaugh’s and Wright’s initial reservations stemmed from the fact that despite nine months of combat on Luzon, neither had heard of this particular Filipino division before (likely because the unit had been organized and supplied by the U.S. military after the Angel’s landings on Leyte in October).

Cavanaugh and Major Wright were led to a meeting room where the Americans and Filipinos reviewed the enemy situations in the area. Following the briefing, Rusty and Wright were treated to a mouth-watering "feast" of fried chicken, a delicacy that seemed almost heavenly after nearly eight months of C- and K-rations. Eating until their bellies were full, the paratroopers were invited to stay the night in camp, another invitation they accepted.

"To this day I don’t know why my battalion commander, or I, allowed ourselves to be away from our unit for that long a period," Rusty commented years later. "But I expect it was our concern over returning in the darkness through the jungle and over the river at such a late hour." The opportunity to sleep in a real bed for the first time in over a year may have helped.

The Beightler Family Reunion

After breakfast on the morning of June 25 (D+146), a guide led Cavanaugh and Wright back to 1st Battalion’s roadside position. The two briefed the COs of A, B, C, G and I Companies on what they had learned from their new friends across the river then the task force continued south, marching all day without incident. While they maintained watches throughout the night, the only banzai assaults the Angels endured were from the jungle’s endless hordes of bugs.

Early the next morning, June 26 (D+147), after swallowing their K-ration breakfasts the Angels continued marching for several hours until word came over the radio that the 37th Infantry Division was only a few miles away. The 37th’s CO was fifty-two-year-old General Robert S. Beightler, Sr. and his son, 1LT Robert S. Beightler, Jr., was serving with the 511th’s B Company, or "Gypsy White", as Communications Officer.

Early the next morning, June 26 (D+147), after swallowing their K-ration breakfasts the Angels continued marching for several hours until word came over the radio that the 37th Infantry Division was only a few miles away. The 37th’s CO was fifty-two-year-old General Robert S. Beightler, Sr. and his son, 1LT Robert S. Beightler, Jr., was serving with the 511th’s B Company, or "Gypsy White", as Communications Officer.

Not ones to miss a good opportunity, Colonel Burgess, Major Wright and Captain Cavanaugh placed Lieutenant Beightler at the head of their column so he would be the first to greet his father at Alcala after the 37th crossed the Paret River.

"This occurred without much fanfare," Rusty noted wryly of the 1235 encounter. "But I’m sure there was some emotion between the two."

A regimental yearbook states that, "The meeting of the Gypsy Task Force and the 37th Division was a fitting climax to the six month long Luzon campaign."

After Colonel Burgess reported to General Beightler, the general turned and made a snide remark to I Corps’ commander General Innis P. "Bull" Swift that the 37th had "saved" the 511th (Parachute Infantry). Offended, and red-faced, Hank Burgess firmly declared that he was under orders to save the 37th and that his paratroopers had out-marched the 37th AND their armored column.

This, of course, angered General Beightler. Standing off to the side, General Swift laughed and said, "Well, you SOUND like one of Joe Swing’s boys!" thus ending the conversation, I'm not sure if Hank knew it at the time, but Swift was actually a good friend of General Swing.

Going Home

General Beightler had Burgess' task force patrol the roads and trails between the Paret River and Aparri from Route 5 eastward on June 28-29, and the Angels found numerous enemy defensive positions and abandoned vehicles, but no Japanese.

General Beightler had Burgess' task force patrol the roads and trails between the Paret River and Aparri from Route 5 eastward on June 28-29, and the Angels found numerous enemy defensive positions and abandoned vehicles, but no Japanese.

Relieved by the 129th Infantry Regiment, Colonel Burgess led the combined force on another day’s march towards the dirt airstrip at Tuguegarao where he went to General Beightler's headquarters to contact the 11th Airborne's HQ back at Lipa to request air transportation for his men. The 37th Infantry was being resupplied via C-47s that were landing at Tuguegararo and Burgess felt that his men deserved a lift back, especially one that would only add twenty minutes to each craft's flight time.

A Sixth Army officer staff officer soon showed up on one of those C-47s with a response to Burgess' radio request: No. The officer then told Burgess to turn his Angels around and march the 45 miles back to Aparri where they would be met by the US naval shipping. After sailing south to Manila, Burgess’ men would then have to march (or be trucked) an additional 80 miles overland to Lipa, a situation the Angels understandably (and colorfully) disagreed with.

"There was no way I was going to march that battalion back up the valley some 55 miles in midday heat of 120 degrees in the shade for three days if we could ride those airplanes," Burgess firmly noted.

B-511's T/Sgt. Alan L. Robbins portrayed the general mood and condition of his comrades after their "long, hot march" from Aparri to Tuguegarao: "(It) was rough walking, and my feet were in bad shape. There were blisters on my blisters."

Ignoring the directive to march his men back home in true Angel-fashion, Colonel Burgess bribed the 317th Troop Carrier Group pilots, the “Jungle Skippers”, with Japanese swords, guns and various other enemy paraphernalia in exchange for flights back to Lipa instead of the 100-mile march-alternative. Although it took two days (July 1-2) to get everyone back, the paratroopers and glidermen alike were happy to be flying, not walking, "home" and with their successful return, General MacArthur declared, "The entire island of Luzon…is now liberated."

True to his nature, Colonel Burgess was on the last craft back to Lipa. He made sure all his men got home, although there were no vehicles available when he got there. The foot-worn Wyoming rancher had to hitchhike his was back to Headquarters to report to General Swing.

Aftermath

Glad to have survived another "combat" operation, Burgess, Major Wright and Captain Cavanaugh led the 511th PIR's contingent back to their Lipa bivouacs to rest, reequip and integrate another batch of replacements, most of whom would come from the fresh-from-the-states 541st Parachute Infantry Regiment, the Winged Panthers.

But even then they questioned the necessity of Task Force Gypsy.

But even then they questioned the necessity of Task Force Gypsy.

Tactically it made sense; by taking Aparri, and its harbor, General Krueger and Sixth Army denied Yamashita's Shibu Group of both a hope for escape and a goal to unitedly withdraw towards. This arguably bolstered a dispersal of enemy power, not a consolidation. And with the 37th Infantry Division pushing north up the Cagayan Valley along Route 5, and Colonel Volckmann's Ilocano guerillas striking Tuguegarao, and with the valley's surrounding mountain ranges acting as natural barriers, US Sixth Army's General Walter Krueger felt that dropping the 11th Airborne Division near Aparri and having it push south would create the perfect "box" to trap the Japanese in.

But Yamashita had already left the box. Aparri, like the Cagayan Valley, is made up of flat, indefensible land; no wonder Yamashita ordered his forces to withdraw for a last-stand in the valley along the Asin River, between Routes 4 and 11. Other Shobu Group units had retreated into the Sierra Madres to the east. The 11th Airborne Division's Gypsy Task Force only saw a few enemy stragglers in northern Luzon and Colonel Burgess, who commanded TF Gypsy, wrote decades later, "The Aparri operation was one long, hot march, but militarily it was not difficult. A drop of flamethrowers and LT Ken Murphy (of HQ11) were of great assistance in taking out pillboxes encountered and continuing the march without interruption."

For many of the battle-hardened Angels, Task Force Gypsy was just "part of the job", but not an exciting part. They would have fought fiercely had it come to that on their several day "long, hot march" Route 5, but the lack of combat with the enemy during the Aparri operation left the Angels feeling like it was, as one paratrooper declared, "

The 11th Airborne's General Joseph Swing wrote home to his father-in-law Peyton March that Task Force Gypsy was a case of too-little, too-late:

"I pleaded with the 6th Army staff to drop the whole division (in the Cagayan Valley) two months ago when they were having such a helluva time in Balete Pass. Had they done so we would have been on the Japs' tail and cleaned out the valley six weeks ago and saved a lot of casualties the other divisions had in making their frontal attack. As it was, they let the Japs withdraw the greater part of their garrison at the northern end of the valley and, unmolested, take them down to reinforce the defenders of the pass. Do you wonder that sometimes I think I'll lose my mind?"

If you'd like to take an ever deeper dive into the Gypsy Task Force,

To learn more about the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of our books on the Angels:11th Airborne Division Operations in Aparri WWII

11th Airborne Division Landing Near Aparri Luzon Philippine Islands WW2