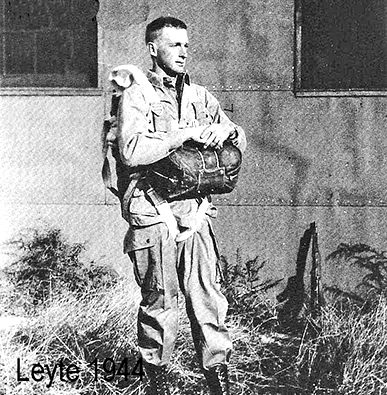

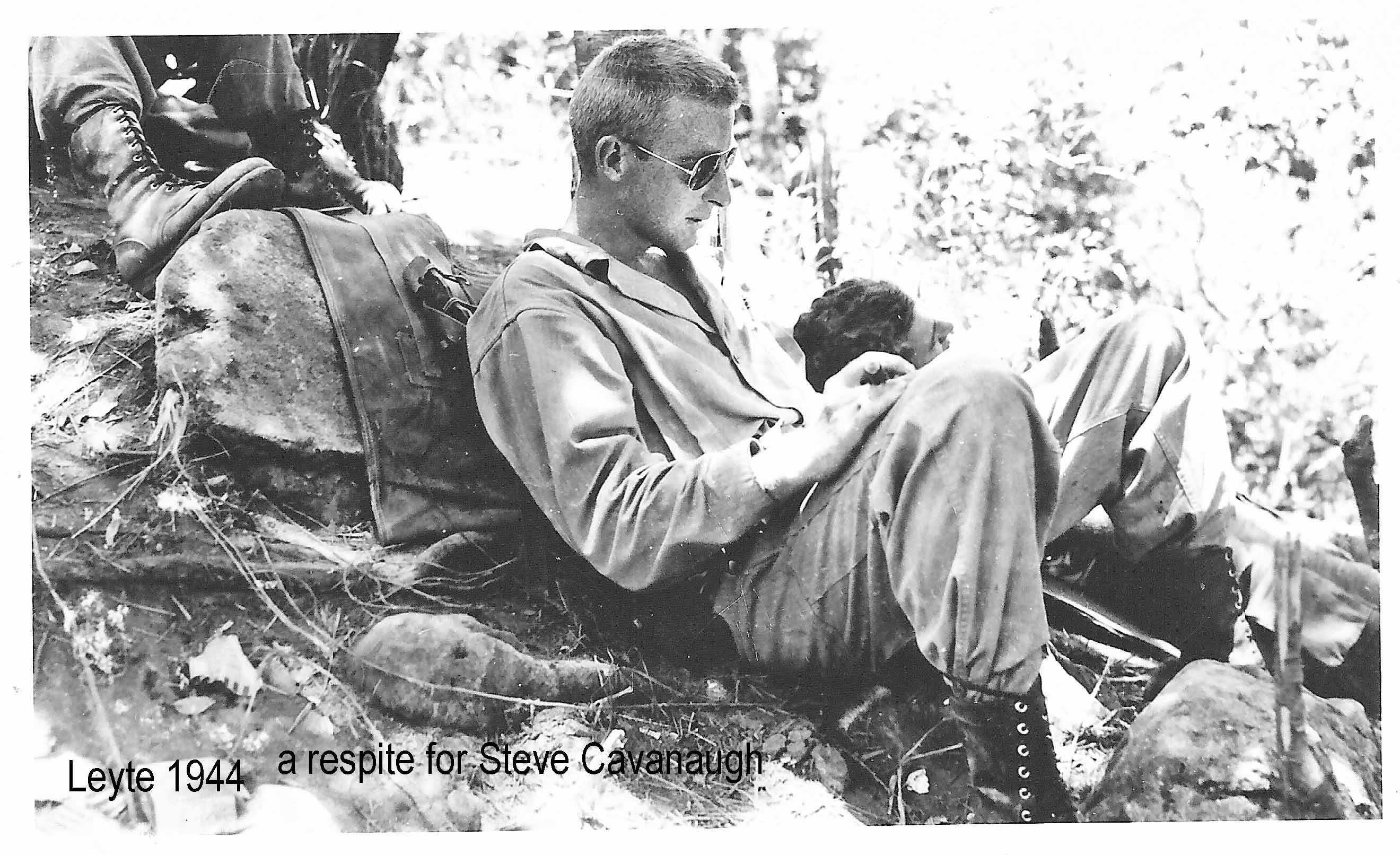

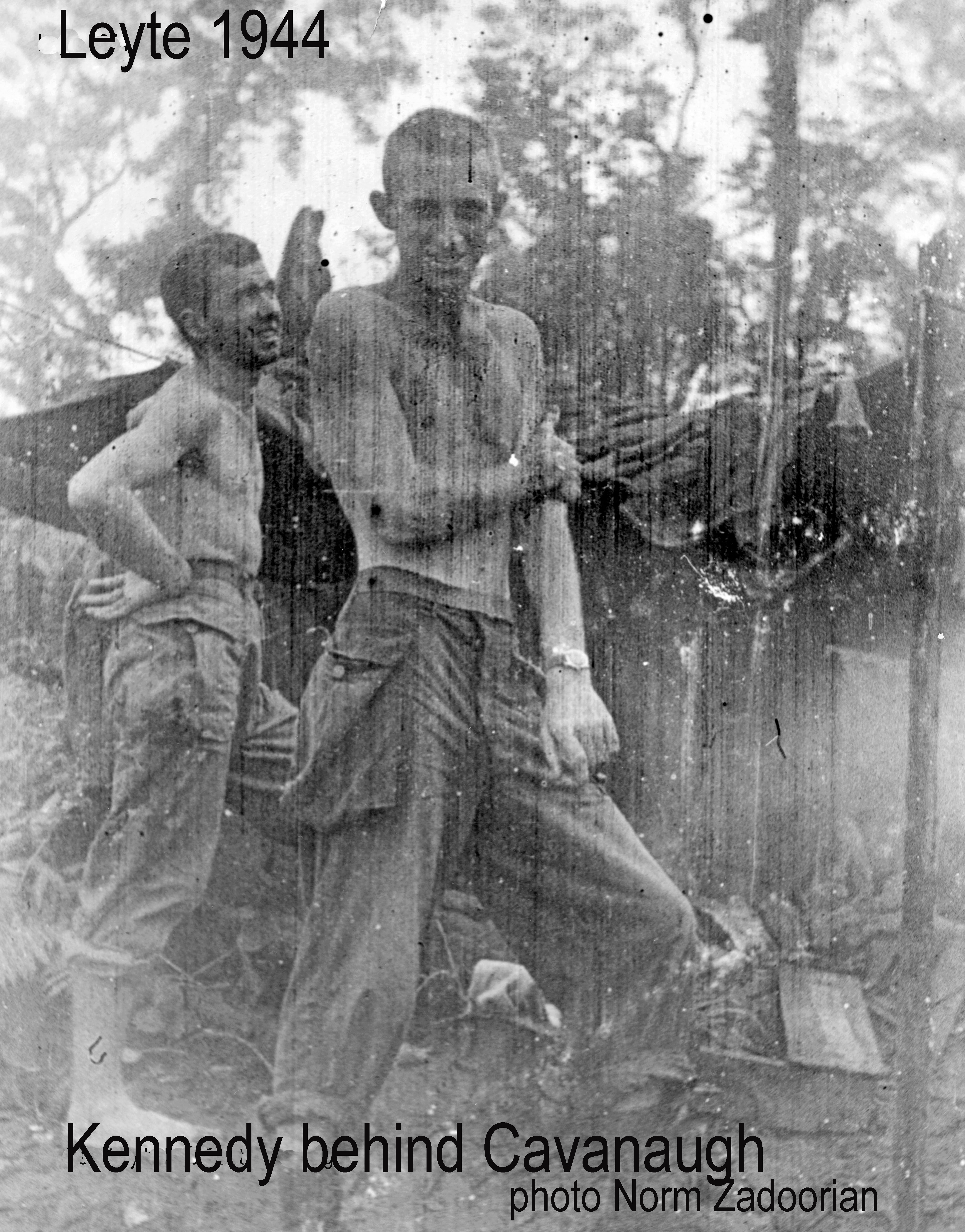

Captain Cavanaugh, Stephen Edward

Commanding Officer, Company D, XO 1st Battalion, 511th PIR

Aug 8, 1921 – Mar 24, 2018 (Age 96) - obituary - gravesite

Citations: Silver Star (OLC), Bronze Star, Purple Heart (OLC) , Presidential Unit Citation, Combat Infantryman’s Badge, World War II Victory Medal, Philippine Presidential Unit Citation Badge, Philippine Liberation Medal with service star, the American Defense Medal, and the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three Battle Stars and one Arrowhead

Ranks: 2nd Lieutenant (California Reserves) May 22, 1942; 1st Lieutenant April 5, 1943; Captain December 4, 1944; Colonel June 5, 1970 (Source: U.S. Army Registrar)

A Call to Arms

by Colonel Stephen E. Cavanaugh, retired

I Heed the Bugle Call

On December 7th 1941 the events at Pearl Harbor changed a lot of things. Everyone viewed the attack on Pearl Harbor as a stab in the back and like most every young man, I was eager to make the Japanese pay for their acts of treachery. I also viewed the war as an opportunity to enter the profession I had always hoped to enter. The rigors of service and the sacrifices of so many were challenges to me. I was enthusiastic about serving and blind to the horrors of what was really happening throughout the world. I couldn’t get into the fray fast enough. Due to my CMTC and ROTC training I had entered the ROTC program in UCLA as a sophomore and consequently was commissioned in May 1942 before finishing my senior year. I was commissioned as a 2nd Lt. in the Coast Artillery but since I had been an engineering student I was ordered to active duty on 15 July 1942 in the Ordnance Corps. This was a branch about which I new nothing whatsoever and I quickly concluded it did not appear to offer the kind of excitement I had hoped to find in a wartime army.

My first duty station was Benecia Arsenal California, a large Ordnance Depot. The Depot employed hundreds of civilian workers, most of them lonely females. I expect it was a most sought after assignment by the small infantry platoon responsible for providing security for the installation. Most infantrymen so assigned appeared hallowed eyed and sadly in need of rest after a brief tour of duty at Benecia. This was not due to the hazards of the duty but from exhaustion from other activities with the young ladies working at the arsenal. After a few weeks at Benecia, I received orders to the 201st Ordnance Ammunition Company stationed a Camp Young in the desert near Indio California.

A few weeks of duty with the “Fighting 201st” resulted in my firm decision that I was not destined to become much of a warrior and was not going to be able to proudly announce after the war how I had single-handedly defeated the enemy. One evening we watched a captured German film showing the training of their parachute troops and the German airborne invasion of the Low Countries. The spark was lit and I resolved to become a parachutists. I had no idea of how to volunteer, but a check of War Dept. publications revealed all and unbeknownst to my then company commander I sent in a letter of application, agreeing as, per regulations…”to jump from and airplane in flight”.

The Silver Badge of Courage

Within a few weeks after volunteering I received a telegram from the War Dept. ordering me to report to Ft. Benning, Georgia for jump training at the Parachute School in Fort Benning, Georgia the Home of the Infantry.

I entered jump training in September and graduated as a qualified parachutist in October 1942 having been physically and mentally stressed during four weeks of very tough training. The Parachute School barracks were situated right above Lawson Field and active Army airfield and where our C-47 transport planes were based. As students we were able to see the jump classes before us as they completed their training jumps and this did much to reinforce our spirits as we were driven beyond our physical capacities by our hard-hearted instructors. One of my class-mates was Lt. Bill Hojanacki who was later to become my assistant platoon leader. Another class-mate was a red haired Jewish boy who became a good friend. Despite his need to wear glasses, he had managed to pass the physical exam and did well through out our first week of physical training without wearing glasses and disclosing his near-sightedness. However, in the second week where we were required to climb up to a fifty foot tower and jump out then slide down a long cable he mistakenly put on his glasses and upon reaching the top of the tower took one look down and refused to jump. He was out of the school before the day was finished.

During our last week of training we were required to pack and jump our own parachutes and needless to say we were very attentive to packing instructions. Rain caused a delay in our first day of jumping so that evening we packed a second chute. The evening was a stormy one and occasioned frequent power outages as we packed our chutes. We became concerned as the evening worn on that we might inadvertently pack something which was not intended to be packed. My first jump was not a thing of beauty. Despite all of our training my body position when I left the aircraft left much to be desired and the opening shock from the chute left me with a head full of stars and large “strawberries” on my shoulders from the harness. I landed on a backward oscillation and only my plastic football style helmet saved my skull. However, other jumps went well and after four more jumps we were qualified as parachutists but were assured we were not yet “paratroopers”. This proud designation would only be acquired after learning the skills involved in both jumping and fighting as parachute infantry. We were constantly told that we should view the parachute only as a means of transportation. The real skills would come when we were able to function behind enemy lines without support or relief until our mission was accomplished.

By this time I was becoming aware that I had bitten off a big chunk to chew and that my role was to become, what was considered by many, a member of an elite band of men not expected to survive many battles. We were told that in parachute units, two lieutenants were assigned each parachute platoon because the survival rate of officers was considered to be very poor. After five qualifying jumps I proudly received my wings...”the silver badge of courage” and was assigned to the 501st Parachute Inf. Regt pending the activation of the 511th Parachute Inf. Regt.

“Vigueur de Dessus”, Strength From Above

My first encounter with the soon to be activated regiment was when I arrived in the Frying Pan area of Fort Benning in December1942 along with a few others awaiting its activation. The regimental commander was Lt. Col. Orin D. Haugen, a chain smoking, no nonsense commander who was soon to earn his well-deserved nickname “The Rock”. Upon reporting in to headquarters I quickly met Col. Haugin who, upon seeing the Ordnance insignia, which was jokingly referred to as a “Flaming Piss Pot”, on the lapels of my blouse, greeted me with the encouraging words... “What the hell are you doing here”? This was an infantry unit and Ordnance officers were viewed with some distain and repugnance. I assured him I was interested in becoming an infantry officer and would apply for same forthwith. He promptly assigned me the glamorous job of regimental Police and Prison Officer. I of course promptly put in an application for transfer to the Infantry so I could be sanitized and become in “The Rocks’ eyes fit to be a member of his command.

I found that parachute officers were a far different type of officer than I was familiar with. Many had been cavalry officers and when they lost their horses and faced the assignment of becoming “tank” riders decided that the parachute troops were more attractive and better fitted to their dashing images of cavalrymen. Parachute officers were an eccentric, resilient, tough and a non-conformist bunch to say the least, in other words they were crazy. One captain I’ll never forget, name not to be mentioned, was really a “role” model. This individual possessed a John Wayne type personality but with somewhat less intelligence. He carried what would best be described as a large Bowie knife in his belt. Often when exiting the door of a barracks he would pause dramatically, suddenly whirl around facing the door, simultaneously snatching the knife from his belt and hurling it at the door-jamb, supposedly killing his would be assassin. Needless to say it was not wise to follow him out of any building. I can’t vouch for the story that he often did the same when carrying a hatchet in his belt. Needless to say he did not last long in the outfit and was not one of our distinguished leaders.

The Christmas of 1942 was the first one away from home and like a lot of other young men at the time it was a lonely one. Being a bachelor I volunteered to be the Duty Officer of our fledgling Regiment on that day and after checking with the duty NCO and ensuring that we were not going to be attacked by the Nazis or Japanese I returned to my small barracks room to open the presents that I had stashed away under my cot and proceeded to open them one by one, feeling sorry for myself and alone in the world. At the end of December our small cadre of officer was moved to Camp Toccoa, Georgia awaiting the arrival of our cadre of NCOs and enlisted men.

Upon our arrival in the rain and mist at Camp Toccoa, and dressed in our Class A “Pinks and Green Uniforms” “The Rock” informed us we would then and there proceed up Mount Curahee, a formidable mountain which we soon were to know quite intimately and in every detail. Leading the way our regimental commander hiked us up and back a distance of some six miles and informed us that we were expected to run the mountain each day. This was a period engrained in the memories of all of us. Tar-paper barracks, the smell of coal smoke and the red mud all contributed to lasting memories of the place. When we arrived at the camp much of it was still under construction and we all pitched in one way or another to get things ready for our recruits. Officers and NCOs alike drew less than inspiring jobs some doing kitchen duties others like myself driving 21/2 ton trucks hauling coal to fill up the newly constructed coal bins. Not the exact picture I had of a glamorous parachute unit.

Ours was to be a novel regiment. The ranks of most parachute units were filled with fully qualified parachute trained personnel. Ours was to be the first to be filled with new recruits to the army without basic training but who had volunteered for parachute training. Our role then was to first provide them basic training and then send them off to jump school. The story of the arrival of these raw volunteers and their careful screening by their new commanders before they could become part of the regiment is another story but needless to say many arrived at Toccoa but many did not stay.

Most of us at the lower end of the food chain were unaware of our future as a unit. We were uncertain as to whether we were to be a separate regiment or assigned to a division. Our role as a unit to be assigned to the “11th Airborne Division” was probably understood by the higher ranks but not those of us. Our assignment to the soon to be activated 11th Airborne Division and to Camp Mackall North Carolina, introduced us into a whole new environment and the beginning of a tough and grueling training routine. Often neglected in our later tales of battle are the stories of how we honed our skills in the sand hills of North Carolina and the swamps of Louisiana. My personal recollections of those days as a very green second lieutenant are of long marches, disastrous encounters with Col. Haugen and trying desperately to keep from screwing up my short-lived military career by displeasing the powers that be. The accounts of some of my experiences are really true (well almost).

For a short time after our arrival at Camp Mackall I continued my assignment as Police and Prison Officer and found myself in frequent contact with Col. Haugen who had definite ideas about the appearance of his regimental area. One of the few times I was able to stay ahead of him was on the occasion of his requirement that I build a bridge over a thirty foot wide ditch, about fifteen feet deep. Its purpose was to permit the movement of troops from a road to a training area. My engineering background helped me in designing a serviceable structure and with a small detail of soldiers I proceeded to cut down a few trees and after “borrowing” 2”x8” planks from S-4 managed in a day or so to build my bridge.

A week later Col. Haugen, his ever present cigarette hanging from his mouth, asked “when the hell I was going to get the bridge built?” I announced the job had been done a week ago. He ordered me into his jeep and off we went to verify my claim and with some reluctance he announced satisfaction for the accomplishment. Faint praise from “The Rock” was the equivalent of receiving the Medal of Honor. Shortly thereafter I received my first assignment as platoon leader of the third platoon of A Co. and I felt I was at last a part of the regiment.

Regiment vs. the Division

Our training involved long days and nights in the field and the almost daily exposure to “Range Road”. Few of us would ever forget “Range Road”. This was the long and torturous route we followed each day just to get to our training area and was what the Bataan Death March must have been like, repeated day after day. To this day I’m convinced the non-jumpers in G-3 at Division Headquarters, who I’m sure disliked our cocky attitude, assigned us the most remote training areas they could find, our regiment was not beloved by the Division Staff. We were felt to be mavericks and troublemakers and prone to feel superior to the rest of the Division (which of course we were). Their attitude was reinforced by complaints of local farmers who reported the mysterious disappearance of watermelons along our routes of march to and from our distant training areas.

Our jump boots were of further concern to Division. The pride we felt as we swaggered around the area with highly polished boots must have really antagonized their non-jumping staff members. To get revenge an order was issued that forbade the wearing of jump boots during training. The excuse given by Division for this draconian order was that it was feared the boots would be worn out and become unserviceable: their wear was prescribed for jumping only. We retaliated by cutting off the issued knee high leggings to a height of about 8” and calling them “glider boots.” This infuriated Division and they charged us with destroying government property.

The officers of the 511th further endeared us to the Division Commander and Staff as a result of the Division Officers Runs. With Gen Swing our Division Commander in the lead he would lead his “pudgy” staff officers in frequent runs throughout the area. These would occur at the end of a training day and officers from each regiment were expected to join in the exercise. The 511th was given the end of the line position because that was considered the toughest. Needless to say these runs were child’s play to our officers who were accustomed to running miles while carrying all sorts of battle gear. At the termination of these “Swing” runs the Division Staff were dragging their posteriors. At that point the 511th officers further endeared themselves to the Division by taking off at a full gallop past the panting and sagging staff to begin a real run. Loved we were not.

In 1940 0r 1941 the U.S. Marines began a parachute-training program that was eventually terminated. Sometime during that period an unfortunate Marine parachutist became entangled with the tail surfaces of the aircraft from which he was jumping. He was pulled around in the air for some time while people in the aircraft and on the ground were frantically trying to come up with a way of saving his life. Eventually a pilot and companion managed to fly under his dangling body and cut the suspension lines connecting him to the jump aircraft and pull him into the rescuing plane. Without question this was a heroic and miraculous rescue.

I mention this story because the U.S. Army decided that what was needed, to avoid a similar accident from occurring to an Army parachutist, was to issue each parachutist a switch-blade knife. This was carried in a special pocket near the collar of the jump suit and was expected to be used by an entangled parachutist to cut himself free from an entanglement and descend using his emergency chute. Unfortunately, but not unexpectedly, our young troopers began to find other uses for this knife and it no longer became an item of issue. Angels we were not.

First Command

My pride and joy was the third platoon of A Co. Among others my soldiers included one who ate glass, one who was a circus stunt motorcycle rider and others with talents unknown to normal humans.

I was fortunate in having as an assistant platoon leader, my friend from Jump School, 2nd Lt. Bill Hojanacki. Bill was a soldier with seven years of enlisted service under his belt and he used to often mention that it took him seven years in the “Old Army” to make corporal. No one in the platoon fooled Bill and I learned much real soldering from him. I was his senior only by virtue of date of rank not by service or knowledge.

My platoon was a diverse group of individuals and I always found myself challenged to keep up with them but I was really proud of them and they always exceeded my expectations. However I often underestimated their skill at getting to me. On one another occasion after what I considered a really bad showing during a training exercise, I proceeded to dress down the platoon with some pretty salty language. Shortly thereafter, a one Pvt. Steven Torres asked to see me and with great respect he informed me that I really didn’t have to use such language while addressing my platoon. After some thought, I agreed with him but I’m afraid that his honest and perfectly correct admonition did little to quell my frequent Irish outbursts.

Another one of my gallant band of soldiers, a Pvt. Mac Arthur, was the cause of my next personal encounter with Col. Haugen. The Pvt. had a small disagreement with the law in a near by town and was hauled off to jail. I was notified by the local authorities that if I wanted to ever see this man again I would have to personally appear at his trial and assume responsibility for his future actions in their town. Having a high regard for the soldier I did what was necessary and returned with him to camp. The next day I was informed that the regimental commander desired my presence without delay. Complying with the order I presented myself before Col. Haugen who gave me the distinct impression that he was displeased that I had bailed out this soldier which had disgraced the regiment by his deeds and who should have been left to the mercies of the local gendarmes. That being said I was dismissed and left with the impression that my future actions would be closely observed and that my career with the regiment was in endanger if not my life.

After surviving this encounter with “the old man” I resolved to keep a low profile. This I accomplished quite well for a while even to the extent of being selected by him to be interviewed by the Division as a possible aide to the Division Commander, General Swing. At the appointed hour I appeared before the Division Chief of Staff along with other candidates who had been nominated from our glider regiments, I was promptly asked if I would like to be the Generals aide. Sticking my foot deeply in my mouth I said “No” that I wanted to remain with my regiment, end of interview. In retrospect I probably had again “endeared” myself with Col. Haugen who I’m sure was asked by the higher ups why he’d nominated some one who didn’t want the job. Maybe this was Col. Hagen’s subtle way of getting me out of the regiment, hmmm?

I look back now and remember how we junior officers use to criticize (to put it mildly) some of the actions of our company, battalion and regimental level commanders and I recognize now how really young and inexperienced they all were and how naïve we were to complain about them. The battalion commander of the 1st battalion, Lt. Col. Ernest La Flamme, a West Point Officer, would have been a junior captain, if that, in the pre-war army; with many years ahead of him before he became a major. Col. Haugen would probably have been a senior major instead of commanding a regiment. They were assuming ranks and positions far beyond their level of experience but that was the acceleration in rank necessary for a rapidly expanding war time army, they were bound to make mistakes yet they led us well.

All of our “senior” officers were indoctrinated with the spirit that went with leading a parachute unit and they saw too it that we “juniors” followed suit. Officers were expected to lead by example and to put the welfare of their men first. While this had always been an old Army custom this spirit was exemplified in parachute units. The officer jumped first out of the door of the aircraft, he ate last in the chow line, he often shouldered the load of a machine gun or mortar tube on long marches and never turned in for the night before checking the feet of his men for blisters. In order to insure that a platoon leader could identify all of his men in the dark after assembly following a night parachute jump, each platoon leader was required to know by heart the name of every man in his platoon, what position they held and where they stood in the squad. Col. Haugen, “The Rock”, saw too it that any officer that failed to measure up was handed a quick trip out of the outfit and many were.

A Daring Leap

In September 1942 I undertook the biggest and most heroic act of my life. Having proposed to my “one and only” back home via letter, I returned to Los Angeles to face the frightening experience of getting married. My lovely bride, a student at UCLA where we had met, remarked that on my wedding day I had the look of a startled deer when looking into the headlights of an approaching car, I was petrified. Having survived the wedding I removed my new bride from the lovely campus of UCLA and a loving family to the un-friendly confines of a one-room apartment, sharing the bath with a stranger, in the small town of Aberdeen, North Carolina, not too far removed from Camp Mackall. If ever a person deserved an award for service above and beyond the call of duty it was my new bride, the place was the pits. I’m sure Aberdeen was and is now a lovely old town but was not prepared for the influx of soldiers and the problems created by them during the war years.

In September 1942 I undertook the biggest and most heroic act of my life. Having proposed to my “one and only” back home via letter, I returned to Los Angeles to face the frightening experience of getting married. My lovely bride, a student at UCLA where we had met, remarked that on my wedding day I had the look of a startled deer when looking into the headlights of an approaching car, I was petrified. Having survived the wedding I removed my new bride from the lovely campus of UCLA and a loving family to the un-friendly confines of a one-room apartment, sharing the bath with a stranger, in the small town of Aberdeen, North Carolina, not too far removed from Camp Mackall. If ever a person deserved an award for service above and beyond the call of duty it was my new bride, the place was the pits. I’m sure Aberdeen was and is now a lovely old town but was not prepared for the influx of soldiers and the problems created by them during the war years.

I shortly moved my beautiful and uncomplaining bride to a roadside hostelry called the Chalfonte. This from the outside appeared to be an old southern, stately mansion and run by a lady called “Happy”. I had been told this establishment had previously been a den of iniquity and sin to say the least. The Madam, recognizing the prospects of making legitimate money by running a hotel for officers and their wives, proceeded to do just that, and Blanche and I became residents. However, the place retained a flavor of its past and it became a great place for an off base bachelor officer hang out. It was not uncommon to see motorcycles driven through the lobby or inebriated officers jumping off of balconies shouting Geronimo or other unintelligible things. One 1st Lt. in particular (his name not to be mentioned and who was later killed in the Philippines) was notorious for his drinking and carousing. After shacking up with his battalion commander’s wife he would return to the Chalfonte to finish off his evenings escapades. Officers and Gentlemen we were not.

Fortunately we became close friend with two other couples, Phil and Aileen Ulrich and Bob Barendse and his wife, both in similar living straits and together we rented a large Model home on one of the beautiful greens of the upscale Pinehurst golf course. Here we lived in a most gracious fashion although we young lieutenants were seldom home.

Traditions

There was a tradition in parachute regiments that all officers before being accepted in the unit were required to under go the ordeals of an initiation ceremony fondly known as the “Prop Blast”. This required each officer to drink an “adult” beverage consisted of a mixture of various highly toxic spirits and to do so without pause and in a limited time. This was followed by requirements such as jumping off any elevated structure at hand, tables, stairs, balconies etc. while loudly counting “one thousand—two thousand etc”. Great bodily harm would normally have resulted from such antics except the previously consumed “Prop Blast” left most initiates so numb and loose that most were indestructible. However, broken arms and legs were not uncommon. The mug used to hold the “Prop Blast” beverage was usually named after the regimental commander and therefore each regiment cherished these vessels I often wonder what ever happened to the “Haugen Mug”.

Privacy in “The Old Army” was a foreign word. Now of days the soldiers are billeted in air-conditioned barracks, often with one or two men per room with such amenities as tables and chairs, throw rugs and often individual beverage coolers. Also a thing of the past is the indignity of the surprise “short-arm inspection”, (to the uninformed let the details of this remain unknown), usually performed in the early morning hours by the unit surgeon. It was designed to identify those with certain diseases, this term has probably lost its’ meaning to our modern soldiers. However, should this custom be reinstated today especially with the integration of female soldiers into the ranks, I’m sure, would find no shortage of volunteers to be the inspectors.

Throughout 1943 units of the regiment received basic, squad and platoon training and eventually were rotated by battalion to Ft.Benning for parachute training. During this period we of the original cadre were sent to specialized schools to further their skills. I went to demolition school and others went to communications or rigger schools. This was a relaxing time for us because jump school personnel were responsible for our troops and we were freed of such responsibilities. By early 1944 the regiment was ready and eager for oversees deployment but had no clue as to our eventual destination.

Our next move was to Camp Polk, Louisiana. Phil Ulrich and I established our wives Aileen and Blanche in a luxurious two-car garage converted into two closet sized bedrooms a bathroom and kitchen. Here we all had a most merry time. After a long days training Phil and I would mix us a concoction of lemon extract powder pilfered from our field rations with some medicinal alcohol, contributed by a friendly battalion surgeon. After adding a bit of water we had an adult beverage that helped us forget the rigors of the day. After a brief stay at Polk we found ourselves enroute to the west coast for deployment to the Pacific Theatre. My bride of 9 months returned to Los Angeles with Millie Varner, another new bride. They drove across the country alone in an old Ford I had purchased a few months previously. Millie’s husband, Lt. Mike Varner was one of the first officers killed in action on Leyte Island, in the Philippines.

“We’re Going Over, We’re Going Over”

Our port of embarkation was Ft.Stoneman located on San Francisco Bay. Upon arriving at the Port we were required to remove all parachute patches and insignia and were forbidden to wear our beloved jump boots. The deployment of an Airborne Division to the Pacific Theater was to be a secret one. We understood this and complied in the spirit of the occasion, however things became complicated. A contingent of Army Combat Engineers were also being shipped out and were billeted close by. Things became tense when we observed that this non-jumping “Leg” outfit was wearing shiny jump boots. Altercations were inevitable and finally culminated by a major brawl at the Stoneman Officers Club where the engineers were encouraged by our officers to remove their jump boots or suffer the consequences. The engineers objected and an altercation of major consequence occurred with the club being all but demolished. The engineers were big in stature and proved able antagonists. The result was that we were forbidden further use of club facilities (what was left of them) and the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment further endeared ourselves to the Division.

I believe it was the 22nd of May 1944 that we boarded our troop transport, the Sea Pike, and began what was to become an infamous three-week cruise to our destination, New Guinea. The trip was to be remembered as one entailing little, and horrible food, hot days, close sleeping accommodations and a thieving civilian crew who were certainly not the pride of the Merchant Marine. Never has any ship been so deserving of being torpedoed after disembarking their troops. A later investigation into the activities of the crew and the ship’s captain showed that our grievances were well founded.

We came ashore in New Guinea near a village called Dobadura and here we unloaded our equipment and rations and ammunition from other ships that were transporting our division. We spent little time on the beach and soon were moved inland about 8 miles to the place which was to be our home for six long, hot, miserable months. Located in a field of Kunai grass we erected our pyramidal tents on frames of bamboo that we cut from the neighboring jungle.

Shortly after arriving I was called again into the presence of the Regimental Commander and informed I was to become the new Company Commander of D Co. in the 2nd Battalion. As a 1st Battalion officer I was unaware that this unit was notorious throughout the 2nd Battalion for deeds unmentionable, so much so in fact that company commanders were assigned to D Co. and relieved at a rapid pace. I think I was the forth or fifth company commander to be so assigned. Though I was flattered and over-joyed at being given a command of a company I later wondered if this was Col. Hagen’s way of trying to get rid of me. In this effort I’m proud to say that, if this was his motivation, he failed.

In all honesty I should inject at this point that my relations with the Regimental Commander had become one of mutual respect. I admired him for his soldierly qualities and for his great love of his regiment. I believe he in turn had come to recognize that I was equally dedicated to his beloved regiment and had put forth a major effort to live up to his expectations. He was my role model of an officer and I had earned his trust and support.

“Fighting” Company D

There is nothing more difficult in any officers’ career than the time arrives when he assumes command of a unit that has been together for a number of years and he arrives as a new comer. This was equally true in my case. I was faced with an additional concern in that I heard through the benefit of “latrine gossip” that my new battalion commander would have preferred that his S-2 take over D Company but had been told by Col. Haugen that I was to have the command.

As I have mentioned, D Company had had the unfortunate experience of having a number of company commanders come and go before I arrived and as a unit they all viewed my arrival with some skepticism and questioned how long I would be last. Recognizing this I felt it best to deal with it honestly and head on by acknowledging their concern and voicing it openly as my own. On the morning of first appearance before the company I introduced myself and remarked “Well, let’s see how long I will last”

My introduction to the Company was anything but encouraging. On the morning following my assumption of command I was awakened by my first sergeant and informed that a certain Private had proceeded to blow his brains out with his M-1 rifle and perhaps I should come down to the company and see the mess. This I did and found what was to be expected when someone places an M-1 rifle against his head and pulls the trigger. Happily there were no further events of like kind and I slowly became adjusted to trying to take over a company of very capable individualists.

My most notorious soldier, Pvt. Bittorie, was an Irish lad who loved to fight and had a reputation in the outfit for being a good guy but frequently at odds with authority. Pvt. Bittorie became involved in an alleged theft of fresh eggs from the battalion mess hall. He was implicated when the eggs were found hidden under the floor of his tent. Without further investigation and no other supporting evidence I had him walking the Company Street under full pack and carrying a machine gun for some period of time. A few months later I recommended this “bad soldier” for a Silver Star for combat action against the enemy in Leyte.

An interesting sequel to this story of this “bad soldier” came 24 years later when my Command Sgt. Major in Vietnam came in to my Command Post and announced that a soldier, who would not give his name, wanted to see me and claiming to have been in one of my previous commands. I agreed to see the stranger. In walked Command Sgt. Major Bittorie, my “bad soldier” who was on his way back to the states and had become one of the Army’s’ most respected and decorated non-commissioned officers. He later went on to become the Command Sgt. Major of Ft. Benning, the home of the Infantry School and the most prestige’s position that could be assigned to an enlisted infantryman.

I found D Company to be a well-trained, capable group of pugnacious soldiers. The platoon leaders Lt’s Carrico, Watkins and Kannely appeared skilled and able so I could do little but try to repair our “bad company” image. We executed a company jump on 11 September 1944 and I received a personal letter from the Regimental Commander commending the company for an outstanding performance, this I immediately posted on our bulletin board for all to see and take pride in. Our six months in New Guinea were designed to acclimatize us to the area and to the jungle warfare facing us. No doubt such was accomplished but it also to a certain extent caused some disciplinary problems that challenged me as a company commander. The shortage of alcoholic beverages led a few enterprising soldiers to improvise a still or two in the neighboring jungle.

These entrepreneurs used some issued food items such as dried raisins, peaches, etc to serve as bases for their concoctions and the resultant brew appeared to be quite satisfactory and no one suffered blindness or death from the beverage produced. Other units produced similar stills and all commanders were concerned that some concoctions might prove deadly. Efforts were made to stop these activities but usually were not too successful.

Recognizing that Rank Has Its Privileges, RHIP, we officers had been allowed to purchase six bottles of alcohol from our officers mess before leaving the states and a month or two after our arrival in New Guinea these orders were delivered. Shortly after I received my shipment I invited my close friend, Foster D. Arnett, to my tent and on a Sunday afternoon we sat down to consume a full bottle of bourbon. Monday morning found me very hung over and I informed my First Sgt. that I had an undisclosed illness and would not be down to the company on that day. Due to the intense heat we kept the sides of our tents rolled partially up to permit air circulation. As I lay suffering on my cot there appeared a detail of D Company personnel, armed with machetes, cutting down the Khuni grass around my tent. Hiding under the G.I. issued wool blanket I sought to avoid detection since I well knew that soldiers had a way of detecting the truth about all manner of things and I did not want to be accused of being too inebriated to report for duty. I believe this was one time that they were deceived, I think. Tropical diseases, poor food and field living conditions undoubtedly reduced our physical condition and we lost a number of trained men from the regiment due to training accidents and disease. Needless to say we became like wild horses, over trained and eager to get into the fight. We were soon to be accommodated.

The Muddy, Bloody Leyte Campaign

From the Beaches to Mahonag

In late 1944 Army forces had landed at Leyte, in the Philippines and Gen. McArthur fulfilled his pledge “To Return” to the Philippines. In November we were ordered to reinforce these operations in Leyte and moved form New Guinea and landed administratively onto the beaches close to the town of Tacloban. Here we again set up a temporary camp and experienced our first “attack” by an enemy force. A lone Japanese aircraft would appear over our beach encampment each evening and release a bomb or two into the jungle before beating a hasty retreat. It became somewhat of a joke to see the futility of these lone pilots’ efforts to “destroy” us. About this time we were also greeted over our unit radios by Tokyo Rose, who welcomed us with familiar music by Glen Miller et al and threatened our ultimate destruction by superior Japanese forces. On the 21st of November we were moved inland a few miles to take over defensive positions and relieve elements of the 1st Battalion 17th Infantry.

The First Day, 21st November

When I assumed command of D Company I found that I had no Executive Officer and therefore went to the regimental commander requesting I be assigned an officer from the regimental staff whom I knew quite well and respected, a highly educated man, a bit older than most of us and with a wife and children. During our stay in New Guinea he proved an able administrator and a great help to me. After our arrival in our new positions, referenced previously, we established a defensive position and awaited attack orders.

My Executive Officer, name omitted for reasons soon to become obvious, and I fastened our ponchos together to form a tent and bunked down for the night. Upon awakening the following morning I found Lt. “ No Name”, fully awake, sitting up smoking a cigarette outside our makeshift tent. After an exchange of “good mornings” Lt. “No Name” announced he was through and that he had battle fatigue. I went along with what I thought was great humor and said something to the effect that the “fighting” had exhausted me also. Of course at that time we had not even been shot at. He replied: “No I really mean it, I’m through”. Now fully awake, I said: “You can’t be serious; the 'Old Man' will have you shot “. The man was adamant and I immediately sought out one of his closest friend in the regiment, Major John Cook. Their families were quite close and I felt Maj. Cook might be able to talk some sense into the cowards head. Cook was unsuccessful in changing his mind and we promptly took him to regimental headquarters where he was promptly placed under arrest. I’m sure “The Rock” would have liked to have tried and shot him on the spot and my feelings were exactly the same.

I later found that this coward had managed to convince the medics in the rear area that he had “battle fatigue”. He was handed all of his records, placed on a ship and subsequently returned to the States. His records mysteriously disappeared before he arrived. I believe this most promising officer had been deeply affected by the serious head wound received by Capt. Tom Brady the Company Commander of A Company. Brady was one of his good friends and I expect it caused him to worry about his own family if he himself were killed or wounded. But there was no officer or man in the regiment that did not have similar feelings to one degree or another and no other became such a quitter. My utter distain for this officer cannot be put into words. It is said that to be good Christian you must “Forgive and forget”. “Forgive” I must, “Forget” I cannot. I’ll leave it to the Good Lord to punish the man since I cannot. All the dead of D Company should cry out for his punishment.

Movement Inland

Elements of our 1st Battalion had been committed to a “reconnaissance in force” the day before we arrived in our new position. Either through the treachery of their Filipino guide or just bad luck the advance company of the battalion, C Company, ran into a Japanese ambush and was surrounded and suffered heavy casualties. The problem was compounded by the fact that our Regimental Commander “The Rock” was with this unit and out of communication with the remainder of the regiment. Division, fearing that the regimental commander had been a casualty directed that new Commanding Officer be parachuted into our position to assume command. Simultaneously efforts to locate the ambushed company were being vigorously pushed. “The Rock” proceeded to take matters into his own hands and after selecting a squad of troopers broke out of the ambush and returned to his command. He promptly directed a relieving force to rescue the besieged company. The Battalion Commander of the company that had been ambushed was relieved from his command for not having been more aggressive in rescuing the ambushed unit and ended up in a similar job in one of our Glider Regiments.

Two days later our 2nd Battalion began a westerly movement inland up into the mountainous jungle, into the rain and mist with no clear orders ever reaching down to the company level. Our maps were of little assistance since the area had never been fully mapped and therefore we simply followed jungle trails leading up into the mountains and to no where. The word getting down to us was that we were to seek out, destroy and cut the supply lines to the Japanese 26th Division, which had been badly mauled by our initial landings and were striving to regroup and counterattack our forces on the beach. The trails were slippery from the monsoon rains and the heavy jungle slowed our movement to a crawl.

Regretfully D Company’s first engagement was not a pleasant one. On the second day as we struggled through the jungle we became engaged by an unknown force and though we suffered no casualties the firing on both sides was heavy and sustained. The thickness on the jungle and the limited visibility meant that identification and location of the presumed enemy force was impossible. I however became conscious of the fact that the firing coming our way was from what sounded to be like that from U.S. M-1 rifles. I became convinced we had been ambushed or had ambushed a friendly unit. I yelled a cease fire order and grabbed a green smoke grenade that was issued to us to distinguish friendly forces and tossed it toward the supposed enemy position. After the green smoke began swirling into the humid air the firing from the other side suddenly stopped. We had been engaged with F Company of our Battalion and tragically they had suffered two casualties. Unfortunately casualties due to friendly fire were and to this day are far from uncommon.

Death from the Skies

Our next position was on a cleared piece of hilltop where we anxiously awaited a resupply of food and ammunition. It came in the form of low flying C-47 dropping boxes of rations and ammunition, a free fall drop without parachutes. This led to the frightening experience of watching fifty pound boxes tumbling through the air and those of us on the ground having no place for cover.

The result of this resupply operation led to our first D Company casualty when on 6th December PFC Mills was struck by a falling box and killed instantly. Members of his platoon dug his shallow grave and we buried him on that hill top, wrapped in his poncho, marking his grave with a crude fifteen foot cross made from a nearby tree. I could do nothing but offer a simple prayer at his grave site. The cross was designed so as to be discernable to a recovery party hopefully at a later date. I later wrote a letter to his family praising his courage but not describing his manner of death, such letters were never a pleasure to write.

Battle Casualty

On the next day, the 7th, we continued our movement up wet, slippery jungle trails and near nightfall our leading elements became engaged with a strong enemy force and we established a perimeter on an open piece of ground, it apparently had once been farmed for camotes. Surrounded by jungle we were harassed by enemy snipers throughout the night and D Company suffered its first combat casualty. Pvt. Pickens violating a standing rule in jungle fighting, got up from his fox hole during the night for reasons unknown and received a chest wound that was to prove fatal. To this day no one knows whether it was hit by enemy or friendly fire.

His sergeant and another man, afraid to stand erect dragged him in the blackness of the night to my foxhole and all three of us pulled him to the center of the battalion perimeter where our surgeon took over. Needless to say it was a harrowing experience since it was pitch black and all of us were afraid we would be taken for the enemy and shot. Our makeshift aid station was a tent made from a poncho and Maj. Platt our battalion surgeon attempted to evaluate the seriousness of the wound using the light of a small flash light. My trip to return to my foxhole was also a harrowing experience and I was as frightened that night as I have ever been. Pvt. Pickens died that night.

Mahonag

Rather than getting bogged down and delaying our primary mission, our battalion commander elected to continue our movement up into the mountains and early the next morning on the 8th of December we moved out from our position leaving Lt. Norris with his platoon from E Company to cover our withdrawal. As we withdrew Norris’s platoon was savagely attack and he was killed in the action. After withdrawing from the Japanese ambush we continued our march seeking a piece of defensible high ground where we could treat our wounded and receive aerial re-supply. The battalion continued to encounter enemy sniper fire, which slowed our progress and while we suffered few casualties from their fire they left us with a feeling every tree had to be closely observed for an enemy and swept with machine gun or rifle fire before we could proceed.

Rather than getting bogged down and delaying our primary mission, our battalion commander elected to continue our movement up into the mountains and early the next morning on the 8th of December we moved out from our position leaving Lt. Norris with his platoon from E Company to cover our withdrawal. As we withdrew Norris’s platoon was savagely attack and he was killed in the action. After withdrawing from the Japanese ambush we continued our march seeking a piece of defensible high ground where we could treat our wounded and receive aerial re-supply. The battalion continued to encounter enemy sniper fire, which slowed our progress and while we suffered few casualties from their fire they left us with a feeling every tree had to be closely observed for an enemy and swept with machine gun or rifle fire before we could proceed.

That afternoon we finally established a large perimeter in another old camote patch identified on the map only as a village called Mahong. Here we set up an aid station designed to permit our surgeon to work more effectively and we took time to clean up and attempt to find out what we were supposed to be doing.

Sheltered by a number of resupply parachutes our wounded were gathered under the care of Maj. Platt who I’m sure felt overwhelmed by the large number of casualties and his shortage of medical supplies. Due to the extreme monsoon conditions we could not be resupplied and Maj Platt remarked that in some cases he had to perform what he called Bulgarian Surgery on some of our wounded. This was surgery without adequate pain killing drugs of anesthesia. Again weather precluded any evacuation of our wounded to the rear and they had been carried along with us as we moved. A number died because of this lack of proper medical care. We had been in almost constant contact with the enemy for almost two weeks and seemingly had accomplished little but kill a few snipers while sustaining numerous casualties. We were tired, wet, cold, very hungry and frustrated with our lack of knowing what we were doing. In actuality we found later that we had inflicted more damage on the enemy than we realized and had seriously disrupted enemy plans to attack with a division sized force on U.S. forces against our beachhead. This attack was to be made simultaneously with a Japanese parachute attack on our rear areas. The parachute attack had occurred on 6th December but was to fail due to the lack of support from the forces we had encountered. We of course knew nothing of this and found out only after coming out of the mountains three weeks later.

We had one period of clearing weather and a C-47 attempted a resupply drop into our position. The pilot was faced with the problem of navigating through the mountains, finding us through the low clouds and then trying to find a suitable drop zone near our position. We heard him overhead and then heard a loud crash and explosion and knew he had gone down. Knowing that the Japanese would be aggressively searching for the wreckage, I was ordered to take the company and try to find the downed plane, secure the site and try to recover any remains and the supplies that the plane had carried. Guided by the smell of burning fuel and engine oil we found the wreckage about a mile from our perimeter. Miraculously the crew chief, who had apparently been standing in the door of the plane trying to spot our location survived. He had been thrown clear of the plane when it smashed into the ground and was founded wandering in a dazed fashion around the wreckage. We found the bodies of one of the pilots lying under one of the engines but no others. We began collecting the few K- Rations and ammunition that had survived the crash and carrying what we were able to salvage back to the perimeter. It was not much.

The food shortage became a major problem and we were required to forage off the land for what food we could find. A wild dog killed by one of my scouts was divided amongst our three platoons. Each platoon received less than a half-pound of meat. The battalion commander was observed in one case helping men probe in the ground with bayonets for camotes left behind by farmers in the mountain farms they had once tended. Our main cooking utensils were our steel helmets and squad cookers, a small one-burner kerosene stove. Each squad was equipped with one stove. Water was boiled in our helmets and what food we had was cooked in them and many concoctions unheard of by man were created. The result was that the helmets became blackened by soot and I have been told lost their tensile strength as a result of the heat they were subjected too. After their use for cooking purposes they became excellent basins for use in washing our sweaty and mud encrusted feet.

The wet conditions resulted in uniforms deteriorating rapidly and our jungle boots simply rotted off our feet. We used the dead as our source for replenishment for footwear. I had to replace my boots with those of a deceased soldier that were two sizes to small and I was forced to cut the toes out in order to wear them. The shortage of food was a major problem. We were solely dependent on air-drops from C-47 or small L-4 light aircraft. K rations were what were normally dropped to us, dependent upon the weather which generally bad. The K ration was a simple field ration usually containing a small tin of cheese or something like Spam, two crackers, and a tin of dried coffee, a small packet of lemon extract which was to be mixed with water, two cigarettes and a small packet of toilet paper. The K ration box was cardboard and within was another box, which was covered in wax as a waterproofing agent. The greatest thing about the K ration was the packaging. The waxed box was great fire starter even in the rain and the outer cardboard box burned well.

These rations, while meager were adequate to keep us alive but were only available when weather permitted. We felt fortunate if we could get one issue a day, this was not often. Supplementing the K ration was the D bar. A bar of strong chocolate which had been prepared with an ingredient to make them resistant to heat and therefore they would not melt. Despite the hunger we all faced there were some whose stomach could not handle the D bar, I was not among these. Wherever possible I would swap, beg or sell my soul for a D bar, these kept me going. The best and most sought after piece of clothing was the issued jungle sweater. While days were warm, wet and sticky the night was damp and cool and the Jungle sweater was an indispensable item. One of my greatest tests was when I was offered to swap three D bars for my jungle sweater. I refused the offer and never regretted the decision. Despite all these adversities morale remained exceptional and the men accepted these conditions with few complaints. I expect that all of us, trained to expect operations behind enemy lines, felt that these conditions were what we had been trained to endure. A full explanation of our means of existence can never be adequate to fully describe the conditions.

Ambush

Shortly after our arrival in this new position in Mahonag I was ordered to take D Company down into a small valley where an enemy supply trail had been observed and I was directed to establish an ambush. Again in the rain, we slogged our way down a slippery slope, found the trail and dug in. I set up positions to cover the trail with rifle and machine gun fire and shortly after our arrival w observed seven of the enemy each carrying a large sack on his shoulders. We opened fire and within a matter of seconds the carrying party was destroyed. We found that the enemy was carrying rice and were probably conscripted Formosans who were part of the Japanese labor force employed to build trails and carry supplies. We spent that night in our fox- holes sitting in foot deep water, miserable, wet, cold and hungry. The next morning we were ordered to return to battalion. I later understand that “The Rock” took our battalion commander to task for removing the ambush since it was on a trail that denied the enemy a means of supply.

The next day, the 11th of December I was ordered to come to the relief of E Company that had been sent out on an ambush mission and who had been attacked and suffered some casualties. We moved into the jungle toward the sound of some firing and found E Company in serious trouble, dug into positions where they had been under constant attack since early that morning. There were seriously wounded men crouched in their fox holes awaiting the next attack and shivering from the cold wet conditions which prevailed in the early morning hours of the monsoon conditions which we were all facing. I contacted Capt. Wade the company commander and informed him I would cover his withdrawal and that speed was of the essence. E Company moved quickly back towards the battalion perimeter and we prepared to meet and enemy counter attack. This soon came but it was not too vigorously launched and we fought a successful withdrawal action back out of the abandon ambush site. D Company suffered only one casualty and it was a serious one, Sgt. Barrario, one of our best platoon sgts., was killed.

Movement West

It now became apparent that our mission had changed from a limited reconnaissance in force to a major drive through the mountains and across the entire Island of Leyte to its’ other side. Destroying any enemy encountered, mainly from the Japanese 26th and 16th Divisions, in route and cutting his supply lines. To this end the 2nd battalion was directed to continue its movement westward and to link up with other regimental elements which had secured, after very heavy fighting, a major position on top of a mountain a few miles away. The battalion began its movement in the early morning of the 18th or 19th of December, (give or take a day or two). With D company in the lead and moving over a Japanese supply trail, we slowly struggled up and down the slippery route all of us weakened by a lack of food and striving to keep our wounded safely on their litters as we toiled up hills and down slippery slopes.

A few hours after we began our movement the battalion was hit by three rounds of artillery fire, which landed behind D company and impacted near the battalion command party. We heard the screaming of the wounded and dying. The battalion commander Lt. Col. Shipley was severely wounded and eventually suffered the loss of a leg, others were killed. I was ordered to continue forward to find the remainder of the regiment while the rest of the battalion was to return to the old perimeter to care for its many casualties. The unknown artillery was reportedly to have come from a U.S. Marine 155mm artillery unit located back on the beaches near our original point of departure. I don’t believe anyone ever really found out why we were taken under fire.

I was given no map as to my destination and no guidance other than that regiment was expected to fire three rifle shots as a guide to direct us toward their position. We simply followed the old resupply trail and hoped to hear some signal firing to give us a direction for movement. Fearing an ambush we moved slowly and scouted the trail as we moved. We eventually heard three shots some distance away and after a few hours thankfully located and reached the regimental position, a hill that became fondly known as “Rock Hill” because “He” was there. In fact Col. Haugen had been personally involved in numerous fights and was gaining a reputation as a true fighter.

Conditions on Rock Hill were extremely bad. The fighting for the position had been intense and enemy dead lay throughout the position. When the hill was finally taken a number of the bodies of our troops that had been killed during the battle to secure the hill were found to have been cannibalized by the Japanese. It was apparent that they also had no food and had resorted to cannibalizing the dead. Our troops were not all that humane either and I stopped a number of our men from using the butts of their rifles to smash out the gold teeth of enemy dead. War is not pleasant

Conditions on Rock Hill were extremely bad. The fighting for the position had been intense and enemy dead lay throughout the position. When the hill was finally taken a number of the bodies of our troops that had been killed during the battle to secure the hill were found to have been cannibalized by the Japanese. It was apparent that they also had no food and had resorted to cannibalizing the dead. Our troops were not all that humane either and I stopped a number of our men from using the butts of their rifles to smash out the gold teeth of enemy dead. War is not pleasant

One of the jobs we all undertook was to throw the remains of the enemy down the surrounding slopes since the smell of death and decay were overpowering. Again, supplies were scarce and we were critically short of food. The result was that by this time the physical condition of most of our troops was deteriorating rapidly. The lack of food, weather conditions, leeches and jungle rot were causing great weight loss, intestinal disease and severe skin ulcerations. In my own case I had lost almost 15 pounds and the back of my hands were so ulcerated with open sores that I was forced to wear an old pair of leather gloves with the fingers cut out to protect them from further infection.

The problem now arose as to who would take over as battalion commander. The remainder of the 2nd Battalion had rejoined D Company on “Rock Hill”, command of the battalion having been assumed by the battalion executive officer an officer the company commanders did not particularly support.

Seldom if ever are commanders selected by their juniors. The Army is not noted for allowing its leaders to be democratically selected. However, In the case of we company commanders in the 2nd Battalion we let our feelings as regards to the selection of our next battalion commander be know. We sought out Col. Haugen and voiced our objections to the assumption of command by the not too highly regarded executive officer. “The Rock” listened and taking our objections into account selected his Regimental S-2 officer, Maj. Holcomb to assume command.

“The Rats Ass” Charge, the Break out

On the 22nd of December, 2nd Battalion was ordered to continue the attack to the west with the mission of linking up with the 7th Division at Ormac on the west coast of Leyte. Despite numerous attempts by F Company to advance against strong enemy resistance, it was decided by Col. Haugen to launch an early morning attack 0n the 22nd on December and D Company was given the mission. At 0400 hours on the 23rd, in total darkness, rain and mist D Company begin to feel its way through the lines of F Company and along the spine of the ridge where the enemy was entrenched. The narrowness of the ridge precluded any sort of attack on a broad front so I placed the company in a column with the first platoon commanded by Lt. Carrico as the attacking element. In actuality the company was attacking with a two or three man front.

I was moving with the platoon leader, Lt.Carrico, behind the first squad when all of a sudden, out of the darkness, there was the sound of gun fire and a bursting grenade and a wild shout of “Rats Ass’’ and the squad surged forward. The scouts had encountered an unsuspecting Japanese guard post whose occupants were relaxing with no apparent thought of any attack coming their way in the darkness and rain. The scouts promptly attacked the position with Pvt. (Bad Soldier) Bittorie firing his machine gun and shouting at the top of his lungs. I don’t think the clear story of what really happened that night will ever be known since it occurred so suddenly in total darkness and rain. The true roles played by PFC Bittorie and Sgt Taylor a squad leader remain untold due to the deaths of the actual participants and the passage of time. What is certain however is that the suddenness of the attack panicked the Japanese. With D Company at its’ heels the enemy sought to reestablish a defensive position against the attack but were hit before they could establish any resistance. This forward surge by the company continued for two to three hours with the enemy running in desperation but losing the race. D Company probably killed at least 100 of the enemy while sustaining the loss of one man Pvt. Sepovada.

With more bravado than sense I sent a runner to the rear to inform the battalion commander that we had overcome the enemy with a bayonet charge and that he was on the run and that we were in hot pursuit. Shortly the runner returned, out of breath, with the orders to cease the attack, to stop, that another unit was to pass through us and continue the advance. Needless to say I disregarded the order feeling that if we paused the enemy would have a chance to regroup and establish defensive positions. Another messenger caught up with us and with some emphasis said that battalion said to stop. Reluctantly we halted and exhausted hit the prone position along the trail.

Shortly thereafter who should arrive but the Division Commander, fresh and clean and leading an element of the 187th Glider Regiment, apparently ready to receive the accolades of the 7th Division as he moved into Ormac. His only comment to me as he passed by was “Nice Job Cavanaugh”; it was not an extremely hearty greeting. My thoughts regarding that gentleman were at that anything but complimentary. D Company never received the acknowledgement deserved for affecting the break out of the Division from the mountains of Leyte except for our Regimental Commander who recognized what we had done. Within a day or two we were out of the mountains on Christmas Day and on the beaches of Ormac.

Summary, Leyte Operations

The rigors of this campaign can be hard to imagine and are difficult to describe. Out of a TO&E strength of 117 officers and men D Company suffered twenty one casualties, of these six had been killed and the remainder wounded. During the 30 some odd days of operations we suffered from cold at night, rain during the day, mud without end, food shortages, a lack of medical supplies, no resupply of boots and uniforms, jungle rot, leeches beyond number, dysentery and fear along with a stubborn enemy who paid a heavy price for his stubbornness. After the first week, with no way to evacuate our wounded we carried them, uncomplaining, up and down muddy trails, through rain and jungle with few ways to ease their pain. The Regiment came out of the mountains with the majority of the troopers suffering from some form of jungle rot and dysentery. However the morale remained high and complaints were few and far between. This was a professional, well- trained regiment with a commanding officer who set an example for all of us to follow.

The rigors of this campaign can be hard to imagine and are difficult to describe. Out of a TO&E strength of 117 officers and men D Company suffered twenty one casualties, of these six had been killed and the remainder wounded. During the 30 some odd days of operations we suffered from cold at night, rain during the day, mud without end, food shortages, a lack of medical supplies, no resupply of boots and uniforms, jungle rot, leeches beyond number, dysentery and fear along with a stubborn enemy who paid a heavy price for his stubbornness. After the first week, with no way to evacuate our wounded we carried them, uncomplaining, up and down muddy trails, through rain and jungle with few ways to ease their pain. The Regiment came out of the mountains with the majority of the troopers suffering from some form of jungle rot and dysentery. However the morale remained high and complaints were few and far between. This was a professional, well- trained regiment with a commanding officer who set an example for all of us to follow.

Rest and Recuperation

From the beaches of Ormac we were moved by truck around the southern tip of Leyte back to our bases at Tacloban. Here we began to receive replacements and spent a good part of each day in the ocean using the salt water to help in clearing up our many open sores and jungle rot and we slowly began to recover our strength and overall health. Our equipment also needed replacement or repair. We spent some time reviewing what we had learned from our grueling jungle operations and in figuring out ways to improve our operations. We had believed that the delay time on our hand grenades, 4 seconds, before detonating was too long and permitted the enemy to throw them back to us or when used as booby traps the delay permitted the enemy to seek cove before the grenade exploded. Through experimentation we learned how to cut the delay fuse on the grenade to about 3 seconds and modified many of our grenades to give us this shorter delay.

A major concern we had which we were unable to correct was that the powder used in our small arms ammunition was not smokeless and as a result when any of our machine guns or rifles were fired their smoke readily identified our positions. We found that the Japanese’s were apparently using a smokeless powder and therefore we were often unable to locate the position from which their fire was coming. We managed to scrounge a number of Browning Automatic weapons (BAR’S) from the glider regiments and felt these to be more effective then our light machine guns in the type of jungle fighting we were engaged in.

I had the unpleasant task of writing letters to the loved ones of our deceased and found this no easy task. We also were directed to provide two men from the company to join a recovery party to return over the path of our advance through the mountains and recover the remains of the fallen from our regiment. This was a most onerous task but one which had to be done. I believe that most of our fallen were recovered but I know of some that were not found until after the war was over. Such was the case of one of my good friends Lt. Varner whose body was not recovered for a number of years. So, for almost a month we rested, received some replacements, reequipped and prepared for our next mission, which was soon to come.

Mindoro

In late January, Army forces landed north of Manila at Lingayan Gulf and the invasion of Luzon had begun. About this time we were alerted for our next mission, a parachute attack south of Manila, which would place the Japanese between two attacking forces one from the north and one from the south. Both forces saw this as a race to seize the city. Our regiment was moved my LCI to the Island of Mindoro with its airfield able to accommodate our jump aircraft. Here for three days we studied maps and reviewed our upcoming operation on an improvised sand table. Our landing zone (LZ) at Tagatay was located on a high ridge overlooking a Lake Taal, a lake in the cone of an extinct volcano. The main road to manila ran along this ridge and provided us a good avenue of approach to the city some twenty miles away to the north.

The 511th Jumps into Battle, Luzon

The orders came down to us to prepare for a jump into Luzon on 3 February 1945. The night of the 2nd we spent packing our supply bundles, issuing ammunition and two K-rations per man. On the 31st of January other elements of the Division had landed amphibiously on the beaches at Nasugbu and were fighting their way northward toward Manila and were to link up with us after our jump on Tagatay ridge some 16 miles north of Nasagbu. I attended a late evening mass on the night of the 2nd along with a large number of Catholics and non-Catholics alike. Needless to say tensions were high and we were all anxious to get things started. I was beginning to feel the effects of jaundice and tropical sprue which almost a year later were to cause me to spent a few weeks in the hospital after my return to the states. The result was a most unpleasant evening spent throwing up in a shell hole along with a good friend Lt. John Norwalk who was equally as ill from yellow jaundice.

Around 0300 hours on the 3rd of February our battalion moved to our nearby departure field. We found “our” parachutes already stacked under the wings of our assigned aircraft and we began the tedious job of chuting up. I emphasize “our” parachutes because actually they were not ours but those of the 503rd Parachute Regimental Combat Team, a unit that were also being assembled for a jump on the Island of Corregidor a few days later and we were using their parachutes. Ours had been soaked while they were in packing sheds during our Leyte operations. The 503rd were to subsequently use our chutes in their daring jump on Corregidor.

The Jump

Putting on a parachute while your body is loaded with ammunition, a rifle and personal equipment is difficult under the best of conditions. In the darkness the job is even more difficult. With aid from the aircrafts crew chiefs and fellow jumpers we struggled into our parachutes, strapped on our reserve chute over our Griswald container that carried our disassembled rifle, hung our small musette bag with our personal equipment under our reserve chute and then sat immobile, like big frogs under the wings of the aircraft awaiting orders to load. Sitting in the darkness surrounded by the familiar smell of aircraft engine oil and hydraulic fuel that only the parachutist can describe, we waited.

Around 0430 hour we began to load into our aircraft. We were so heavily loaded and ungainly that we had to be assisted up the small ladder into the aircraft. We struggled into our canvas bucket seats, already somewhat exhausted and began the unpleasant job of sweating out the jump. The officers are always so busy with their responsibilities of assembling their troops, checking on each mans readiness and stacking supply bundles near the door of the aircraft that they undoubtedly feel less anxiety than the men who simply sit and wait.

We took off in darkness with the aircraft carrying our battalion forming up in three aircraft “V’s” and then in turn forming into nine aircraft “V’s”. As we flew north the darkness began to lessen and peering around our stacked supply bundles in the door of the aircraft I tried to get oriented as to where we were. I soon recognized the shores of Luzon and began sweating out the appearance of our LZ, which was to be marked by smoke placed by our pathfinder team. The team, led by Lt. Hoover, hopefully had infiltrated over the past three days from the landings at Nasagbu, through enemy lines to our LZ. Almost immediately I saw that we had a major problem. We were flying over a deep cloud cover, which blocked all visibility and unless it cleared the pilots would never find our drop zone.

Our standard jump procedure (SOP) for mass jumps called for the lead aircraft to begin jumping at the appropriate time upon reaching the Drop area. This then was the responsibility of the lead aircraft commander, to turn on a red light to the right of the jump door about five minutes before reaching the drop zone. This enabled the jump master to get the jumpers to their feet, no easy task loaded as we were, check each mans equipment, hook up all jumpers to the anchor cable which ran the length of the aircraft and to close up the jumpers as closely as possible to allow for a rapid exit. Upon reaching the drop zone and observing the proper markings and direction of the wind, the lead aircraft commander would then turn on the green light and the jumpers would exit the aircraft. These preparations were occurring in each aircraft and the jump masters, usually the officer who led the jumpers, would be peering out of the doors of their respective planes looking not only for the drop zone but also toward the lead aircraft. The SOP was to begin jumping when you saw the chutes from the lead aircraft begin to open.

One Company Jumps Early

As I anxiously watched the cloud cover below, it suddenly ended and we broke out into clear, bright weather and I was looking down onto broad patches of open ground, seeing Lake Taal to the west and trying to compare the topography of the area to the sand table we had been studying back in Mindoro. We were flying at about 500 to 600 feet above the ground and I glanced back to see the aircraft flying in their V’s behind and above us, it was a dramatic sight. Suddenly I noticed chutes in the air from the flight just behind us and I realized that something had gone amiss. There were no chutes coming from the aircraft in front of us and there was no indication from our pilot that he had yet spotted the drop zone. It was apparent that some pilot in one of the aircraft behind us panicked and had initiated the jump action. The planes in that group V’s had in turn, according to our SOP, had followed the leader and turned on their green lights and the jumpers had exited the aircraft. This meant that a large group of troopers were going to be separated from the rest of the regiment and what made it worse was the fact we had been flying south, away from Manila and their jumping prematurely could very well place them in close proximity to the enemy.

We Earn Our Pay

Just about this time the drop zone came into sight, the red light came on next to the jump door and I could see in the distance the colored smoke from out pathfinder team rising from the ground. I stood up the jumpers, got them properly hooked up and a few seconds later observed jumpers leaving the planes ahead of us before our green light came on. We had stacked three supply bundles in the door of our aircraft, bundles containing machine guns, mortars and ammunition and these had to be pushed out of the door first. After the crew chief and I wrestled them out of the door I turned to the anxious faces behind me, said “Lets Go” and out we went. I’ll never forget the look on the face of the aircraft crew chief as we left the plane. His expression clearly said “Are these guys crazy”.

As in all jumps, there is a moment of sheer confusion as your body gets smashed by the prop blast of the aircraft then is twisted and contorted by the opening shock of the parachute and then you find yourself hanging quietly beneath a canopy of silk anticipating and preparing for the landing. Along with everything else you are concerned about meeting enemy resistance on the LZ, freeing yourself from your parachute and preparing for a fight. Fortunately we met no resistance. After hitting the ground I got out of my parachute harness and as I was getting my rifle reassemble up ran a wide-eyed Philippine boy wondering who and what these strange people were who had descended from the sky. After recovering our supply bundles we quickly reassembled in a previously planned assembly point and then moved toward Highway 17 a main road leading to Manila. As the regiment began its reassembly, down the road from the north came Capt. Wade and F Company, the unit that had jumped early. There were no questions asked at the time and we all felt relieved that they had not encountered enemy resistance.

Battle for Imus