MacArthur's Angels: Mac & the 11th Airborne Division

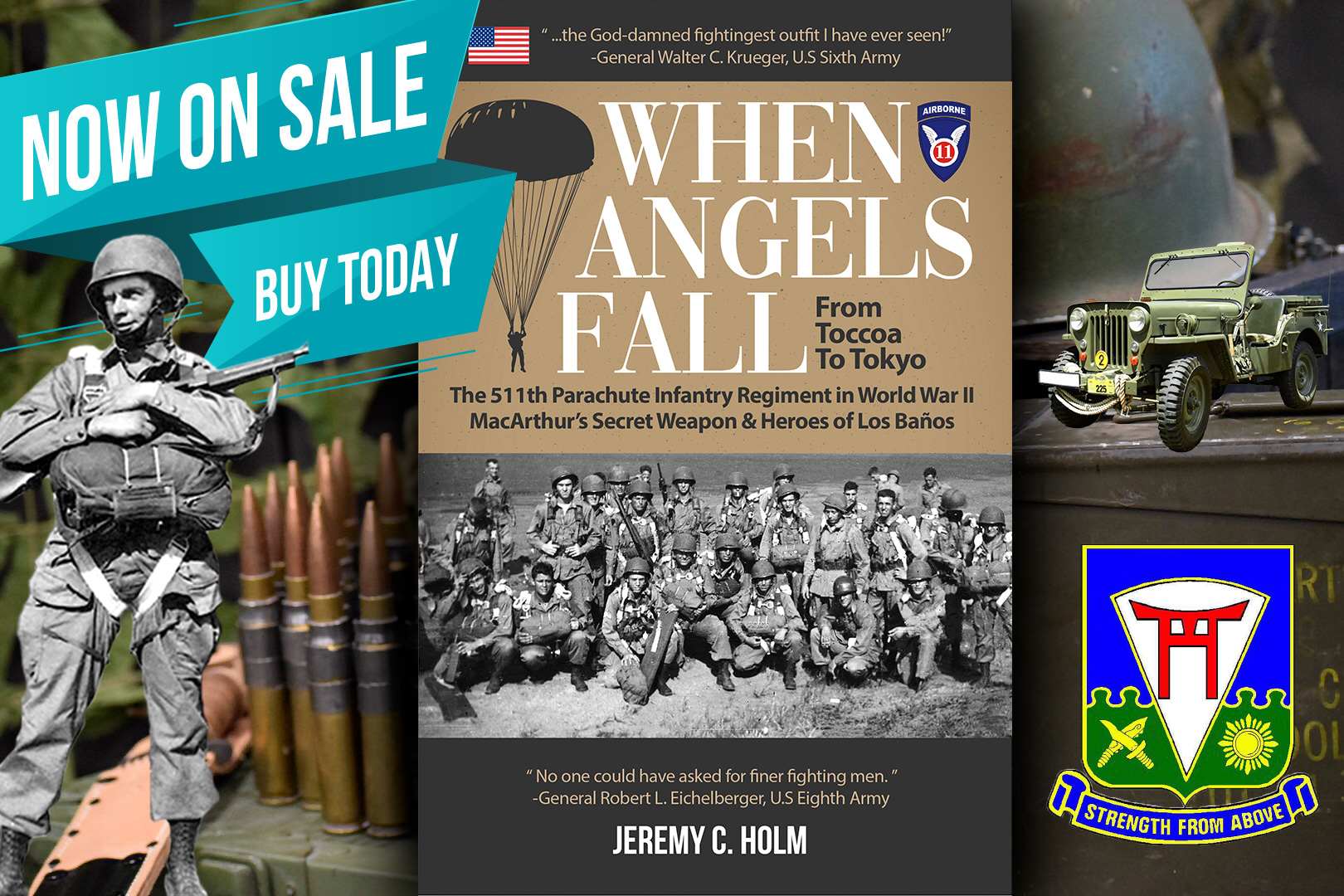

With the anniversary of General Douglas MacArthur's death (January 26, 1880 – April, 5, 1964) approaching, I thought I would share a fascinating, yet abbreviated history of Mac and my grandfather's 11th Airborne Division which was a favorite "secret weapon" for The Napoleon of Luzon in World War II (a full review of MacArthur's relationship with The Angels can be found in my book, "When Angels Fall: From Toccoa to Tokyo, The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II" - Amazon $14.95). The Angels were associated with or touched by several of the war's most historic moments, including some that would thrill military historians and enthusiasts around the world.

With the anniversary of General Douglas MacArthur's death (January 26, 1880 – April, 5, 1964) approaching, I thought I would share a fascinating, yet abbreviated history of Mac and my grandfather's 11th Airborne Division which was a favorite "secret weapon" for The Napoleon of Luzon in World War II (a full review of MacArthur's relationship with The Angels can be found in my book, "When Angels Fall: From Toccoa to Tokyo, The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II" - Amazon $14.95). The Angels were associated with or touched by several of the war's most historic moments, including some that would thrill military historians and enthusiasts around the world.

A Meeting of the Generals - May 1944

As the 11th Airborne Division sailed for Dobodura, New Guinea in May of 1944, their commanding general Major General Joseph May Swing was was headed for Australia to meet with General MacArthur. Swing was widely recognized as one of America's most qualified airborne commanders having been artillery commander for the 82nd Infantry Division when it was converted to the 82nd Airborne Division where Swing quickly became a disciple of airborne tactics.

After forming the new 11th Airborne Division at Camp Mackall, North Carolina in November of 1942, Swing had flown to North Africa to advise his old Westpoint roommate General Dwigh D. Eisenhower on the airborne operations in Sicily. After returning home General Swing chaired the famous Swing Board at Camp Mackall which published the training circular which became known as “Employment of Airborne and Troop Carrier Forces” which General Douglas MacArthur certainly received and studied. After Swing's 11th Airborne Division performed so admirably during the test known as The Knollwood Maneuvers in December of 1943 the War Department changed its tune regarding the future of airborne divisions, another victory that MacArthur surely noticed about the 11th Airborne as he himself was more than happy to stick it to Washington.

While I have been unable to uncover any requests made by MacArthur to have General Swing's division sent to his theater, I imagine it was with some satisfaction that he received word that the 11th Airborne Division was being sent his way. To that end, in May of 1943 General Swing headed for 77-79 York Street in Syndey, Australia to meet with General MacArthur and his staff for several days of briefings to learn what role his beloved division would play in the Pacific. For now, the Angels would undergo several months of theater training on New Guinea, though the fresh division would remain in reserve for ongoing operations around Hollandia to the island's north.

After that the Angels would mostly likely be used heavily during the invasion of Luzon (with a bloody and grueling stop on Leyte first).

Eager to lead his division into combat, General Swing told his men, "Think, eat and dream of war. We’re fighting a desperate enemy."

"Tell Your Boys I'm Real Proud of the 11th Airborne"

Six months later Swing's division sailed 2,100 miles north into Leyte Harbor and two weeks later they were heading into Leyte's mountains in a Reconnaissance in Force that quickly turned into a major operation after Japan began pouring reinforcements onto the island. For nearly five weeks my grandfather's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment under Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen would take the brunt of the assault with other division elements in support.

Six months later Swing's division sailed 2,100 miles north into Leyte Harbor and two weeks later they were heading into Leyte's mountains in a Reconnaissance in Force that quickly turned into a major operation after Japan began pouring reinforcements onto the island. For nearly five weeks my grandfather's 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment under Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen would take the brunt of the assault with other division elements in support.

While my book, "When Angels Fall" covers the campaign in greater detail, I'll leave you with the words of one paratrooper who said, "After Leyte, Hell was a vacation."

In the middle of their campaign, in a strange twist of luck the Angels happened upon an enemy map of California with invasion sites clearly marked (it was found in a dead Japanese officer's satchel). Two paratroopers of the 511th PIR's G Company, PFCs Charles Feuereisen of New York City, NY and Ralph Merisiecki of Cleveland, OH, were tasked with taking the map back to General Swing's CP outside Burauen. The duo then proceeded to head for Tacloban where they would deliver the map to General MacArthur's staff and then find a lift back to their unit.

Since they had to go to MacArthur's beautiful headquarters in the Price House, PFC Feuereisen turned to his comrade and noted, "Ralph, we'll never get this close to General MacArthur again. Why don't we visit him?"

Undeterred by staff officers who tried to impede their efforts, the two battle-worn Angels made their way through the building until they found themselves outside the general's office and encountered Lieutenant Colonel Roger 0. Egeberg, MacArthur's physician. Feuerseisen and Merisiecki explained their mission which MacArthur overhead and before long he ordered the Privates into his private office and greeted them with a smile and a handshake. MacArthur and the two Angels spent ten minutes discussing the 11th Airborne's actions in Leyte's mountains while overlooking operational maps. The privates were surprised with just how aware the general was of their beloved division's undertakings and they boldly asked why the newspapers back home were not reporting on their victories and advances.

General MacArthur explained that he was leaving the 11th Airborne out of official communiques to keep their presence a secret from the enemy as they were a "secret weapon." That satisfied the two paratroopers, but before leaving, Feuerelsen asked another question his comrades had been wondering about: why was the 511th being used as ground infantry and not jumping behind the enemy lines as they had been trained to do? MacArthur assured him that they would be jumping soon as he had something special planned for them.

Perhaps to further assuage the mighty Angels' pride, as Feuerseisen and Merisiecki made their way out of the Price House, General MacArthur declared in front of all the generals and other Brass who were waiting to meet with him (and who were annoyed that two lowly privates had taken so much time), "Tell your boys that I’m real proud of the 11th Airborne."

The general's Christmas Eve message distributed throughout the theater made let everyone know just how proud he was. MacArthur noted, "Operating in the central mountain regions southeast of Ormoc, the 11th Airborne has been waging aggressive warfare along a wide sector. The Division has annihilated all resistance within the area."

Several paratroopers of the 511th PIR later emphasized to me MacArthur's correct usage of the word "all."

MacArthur, the Angels and the Landings at Nasugbu

While the 11th Airborne recuperated from their Leyte ordeals on Bito Beach south of (they were only given about three weeks to rest and reequip), General MacArthur and US Eigth Army's General Robert Eicheilberger had been planning what role the new Eight Army (which in the end would consisted of mainly and almost solely the 11th Airborne Division) would play in the invasion of Luzon.

Eichelberger wrote his wife Emmalina, “I am very keen about this 11th Airborne. They are small in number, but they are willing to fight.”

In the end, the plan put in place by Eichelberger and the 11th's General Swing would involve landing the Angels' glider regiments and engineering and other supporting units amphibiously at Nasugbu south of Manila on the west coast. The landing force would then push inland and north towards Tagaytay Ridge which the 511th PIR would parachute onto and then the entire force would push northward into the "soft underbelly" of Manila (only it wasn't soft, it was the most fortified approach into the city and labeled "The Genko Line").

General MacArthur approved of the plan, but he rightfully worried about what would happen if the 511th dropped onto Tagaytay Ridge only to find the rest of division stopped somewhere along Route 17. MacArthur told Generals Eichelberger and Swing to only allow the 511th to drop if the regiment could be reached by the landing force within twenty-four hours, a missive that the Angels obeyed and the division assembled on Tagaytay Ridge on February 5, 1945.

Letters Home

MacArthur kept close tabs on the 11th Airborne, especially the 511th PIR, and even took time to meet with its members when they were near his Luzon CPs. There are several instances of the general writing personal letters to the wives and families of Angels who fell in combat. One example of this is from my grandfather's D Company of the 511th. When D Company first pushed northward towards Manila, they were tasked with capturing a bridge in Imus on February 4, 1945 that was guarded by an enemy garrison. D Company fought the Japanese in a stone courtyard and while they achieved their objective, they suffered several casualties in the process, including S/Sgt. Henry F. Gumm (KIA), the rigger who helped train the 511th’s men at Fort Benning.

MacArthur kept close tabs on the 11th Airborne, especially the 511th PIR, and even took time to meet with its members when they were near his Luzon CPs. There are several instances of the general writing personal letters to the wives and families of Angels who fell in combat. One example of this is from my grandfather's D Company of the 511th. When D Company first pushed northward towards Manila, they were tasked with capturing a bridge in Imus on February 4, 1945 that was guarded by an enemy garrison. D Company fought the Japanese in a stone courtyard and while they achieved their objective, they suffered several casualties in the process, including S/Sgt. Henry F. Gumm (KIA), the rigger who helped train the 511th’s men at Fort Benning.

Now given the general's well-known penchant for publicity, he may have written to the Gumms since they were America’s first family to hang a four-star flag in their window with Henry’s three brothers serving in in the Army and Army Air Corps. Regardless, Gen. MacArthur cared for the common soldier and he wrote Henry’s mother, saying, “His service under me in the Southwest Pacific was characterized by his complete devotion to our beloved country and by his death in our crusade for freedom and liberty he is enshrined in its imperishable glory.”

One of the "Fightingest" and Bravest Soldiers in the Pacific

Two weeks after Sergeant Gumm's death, General MacArthur visited the 11th Airborne's General Swing for lunch on February 21, 1945 and briefings to go over the Angels' advances. The under-strength division had liberated southern Manila, including Cavite, Nichols Field, Intramuros, Fort William Mckinley and more. MacArthur and Swing discussed the enemy's resistance, which was stronger than Mac had anticipated at Nichols Field, and the two old soldiers also talked about a younger one who had shown incredible bravery on the battlefield.

When the Angels' Pierson Task Force had moved to eliminate the Japanese on Mabato Point Laguna de Bay's west coast, some of the enemy had tried to escape by heading south, but instead of freedom they found the 511th PIR's waiting 3rd Battalion and their supporting Filipino guerillas who decimated the enemy. HQ3-511’s T/Sgt. Miles T. Lowe commanded a remote machine gun position and on the night of February 20 (X+20), Lowe and his twenty-four men were attacked by between 200-300 Japanese. While the paratroopers held their own during the first four assaults, ammunition began to run low. Believing the Japanese were massing to attack again, Lowe led a small group out to collect enemy weapons in the dark and returned with seven Japanese machine guns and two mortars. Taking up their positions once more, the Angels successfully held off a fifth Banzai charge and enraged by their lack of success, the remaining Japanese assaulted from the front and the rear. Miles personally killed eight enemy in hand-to-hand combat and the next day, T/Sgt. Lowe’s men counted fifty Japanese dead by his hands alone.

For his leadership at Mabato Point the generals elected to award T/Sgt. Lowe a battlefield commission to 2nd Lieutenant and the Distinguished Service Cross, calling him one of the “fightingest” and bravest soldiers in the Pacific.

MacArthur and the Los Baños Raid

As the Angels continued their fight for Manila, General MacArthur and his staff grew more concerned for the civilian prisoners being held by the Japanese in internment camps across Luzon. As the Allies pressed forward, the fear was that the enemy would rather kill all the prisoners than allow them to be liberated. While I cover the 11th Airborne Division's historic raid on the internee camp situated at Los Baños in an earlier blog post, General MacArthur played a part in the Angels' successful operation.

As the Angels continued their fight for Manila, General MacArthur and his staff grew more concerned for the civilian prisoners being held by the Japanese in internment camps across Luzon. As the Allies pressed forward, the fear was that the enemy would rather kill all the prisoners than allow them to be liberated. While I cover the 11th Airborne Division's historic raid on the internee camp situated at Los Baños in an earlier blog post, General MacArthur played a part in the Angels' successful operation.

First off, the directive to liberate such camps in each unit's operating area came from Mac himself. After the enemy massacred POWs on Palawan at 2pm on December 14, 1944, an enraged MacArthur wanted everything possible done to prevent such carnage from happening again. He ordered his staff and forces to plan operations to find and liberate such camps, with Cabanatuan being the first. On January 30, 1945, after traveling thirty miles behind enemy lines, rangers of the 6th Ranger Battalion crawled more than a mile on their stomachs and freed over 500 POWs with support from the Alamo Scouts, including former 11th Airborne members.

Following the equally successful raid at Santo Thomas, General MacArthur sent word to Eighth Army’s Gen. Eichelberger that he wanted a similar mission effected to rescue the 2,142 internees at Los Baños. On February 12 (X+12 for the Angels), Eichelberger passed the operation to Gen. Swing in whose “area” the camp resided, but due to their heavy engagements with the Japanese in Southern Manila, Swing asked XIV Corp’s Gen. Oscar Griswold if they could postpone the mission. Griswold agreed.

The Angels effected their historic raid on Los Baños eleven days later on February 23, 1945 and after eliminating most of the enemy guarding force loaded the civilian men, women and children into Amtracs for their withdrawal across Laguna de Bay. Before they left, however, Colonel Courtney Whitney, a former Manila lawyer who was now serving on Gen. MacArthur’s staff, exited one of the Amtracs and disappeared into the camp. A short while later Whitney and his interpreter, along with two Amtrac crewmen, reappeared carrying boxes. Whitney directed the classified Philippine Regional Section which coordinated with guerrilla forces (most of the Filipinos disliked him) and it is believed that the retrieved boxes held documents used in later war crimes trials.

When General MacArthur learned of the operations complete success, he declared, "God was with us today and we should be thankful for all he did to help us out."

General Swing wrote that after reading MacArthur’s note, “(O)ld Walter Krueger made a sour face and said he was pleased. You see we don’t really belong to his army; we were just taken over from the Eighth and there’s just a ‘wee bit’ of jealousy on somebody’s part."

On to Tokyo

After the Angels' bloody battles for southern Luzon, on June 23, 1945 the division's Task Force Gypsy jumped on the Camalaniugan Airfield outside Aparri to help seal the Cagayan Valley and block any enemy forces retreating northward towards the coast. Given that other American and Filipino forces had already taken Aparri, many of the Angels were less than enthusiastic about the operation. Captain Steven Cavanaugh, XO of the 511th PIR's 1st Battalion, said, "I… felt the operation to be more of a newspaper stunt by General Macarthur’s Headquarters more than anything else.”

After the Angels' bloody battles for southern Luzon, on June 23, 1945 the division's Task Force Gypsy jumped on the Camalaniugan Airfield outside Aparri to help seal the Cagayan Valley and block any enemy forces retreating northward towards the coast. Given that other American and Filipino forces had already taken Aparri, many of the Angels were less than enthusiastic about the operation. Captain Steven Cavanaugh, XO of the 511th PIR's 1st Battalion, said, "I… felt the operation to be more of a newspaper stunt by General Macarthur’s Headquarters more than anything else.”

Whether it was or not, when the task force returned to the regiment's bivouac at to Lipa Gen. MacArthur declared, “The entire island of Luzon…is now liberated.”

His motto then became one that was shared by the 11th Airborne itself: "On to Tokyo!"

Rumors still swirled about the Angels’ fate, however. Men who had been together since Camp Toccoa now looked north and wondered if they would indeed “Jump on Tokyo.” Scuttlebutt said they would drop on Japan before the main assault began akin to the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions’ operations in Normandy. Others claimed the division was bound for China while some opined that Formosa (Taiwan) was their goal.

Either way, General Swing said of General MacArthur, “I have a sneaking idea that he believes as we do, that we can handle just about twice as many Japs as any of the others.”

But while his division made final preparations for their assault on mainland Japan, the first atomic bomb was dropped Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. While the world was stunned by the device's destructive capacity, the Angels themselves shrugged and went back to work.

It wasn't until a few days later on August 9 when another atomic bomb was dropped on Nagasaki that Japan officially entered into peace talks. At 0400 on August 11 (D+192), two days after the bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, the Angels received orders to prep for departure “sometime in the future.” That order was updated at 1200 when an 11th Airborne liaison with Air Force HQ in Fort McKinley was told that transports would start landing on the Lipa Airfield in four hours for flights to Okinawa. The bigger news was that the Angels would land at Atsugi before heading to Tokyo to disarm the Imperial Palace’s royal guards, then protect the Imperial family from fanatical Japanese.

Smiles broke out amongst the Angels. The Screaming Eagles may have taken Hitler’s Kehlsteinhaus (Eagle’s Nest) in Berchetgarden, but Colonel Edward H. Lahti’s boys agreed that only the 511th PIR could handle being the first full regiment to step foot on Japan’s mainland and defend the Emperor.

Gen. Swing was pleased to hear that his would be the first Allied division to land in Japan. So pleased, in fact, that Jumping Joe walked into the division hospital and boomed, “I want every man that can walk…out of here today. We’re leaving the island; we’re going to Japan.”

By 1300 the entire 511th had been recalled from rest camps (those who didn’t make it would have to travel by boat) and the regiment moved in borrowed trucks or by rail to the airfields just as 351 C-46s, 151 C-37s and 99 B-24s began flying in. Under control of the 54th Troop-Carrier Wing’s MG William Ord Ryan, the planes were loaded at the Lipa, Nichols, Nielson and Clark Airfields then prepared to head for Okinawa as General MacArthur himself looked on.

A few days later while the 11th Airborne waited anxiously on Okinawa Lieutenant John "Johnny" Ringler, commander of the 511th PIR's B Company of Los Baños fame pounded down Officer's Row in shorts and jump boots, shouting “It’s over! It’s over! The war is over!” as he waved his hands.

“My impressions of that day and the great relief we all felt hearing that the war was over are hard to describe,” D Company's Captain Steven Cavanaugh noted with deep emotion. Instead of jumping onto mainland Japan during Operation Downfall, during which the division expected heavy casualties, the Angels would instead fly to Japan on luxuriously padded seats.

Japanese Delegation Flies Over the Angels

While they waited for the final command to board their craft, on August 20 the Angels watched a specially painted (white with green crosses) Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber fly overhead, lit up by nearly every spotlight on the island. They were surprised to discover that the twin-engine craft, with the call-sign "Bataan 1", carried some of Japan’s delegates on their way back to Tokyo after meeting with General MacArthur's staff in Manila.

While they waited for the final command to board their craft, on August 20 the Angels watched a specially painted (white with green crosses) Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber fly overhead, lit up by nearly every spotlight on the island. They were surprised to discover that the twin-engine craft, with the call-sign "Bataan 1", carried some of Japan’s delegates on their way back to Tokyo after meeting with General MacArthur's staff in Manila.

A few days later, August 24, the Angels received Field Order No. 34 outlining their final instructions upon landing in Yokohama, including the need to remove all Japanese within a three-mile radius of the airfield and to guard General MacArthur and his entourage.

It was official: General Swing’s Angels would do what Kublai Khan’s fleet could not do in 1274 and 1281. The 11th Airborne Division would be the first full military unit in history to occupy Honshu.

Atsugi Landings and General MacArthur's Honor Guard

When the Angels' vanguard of pathfinders and their recon platoon landed on August 28 first landed at the Atsugi Airfields outside Yokohama, Japan on August 28, 1945, they did so alongside Colonel Charles Trench of MacArthur’s HQ.

When the Angels' vanguard of pathfinders and their recon platoon landed on August 28 first landed at the Atsugi Airfields outside Yokohama, Japan on August 28, 1945, they did so alongside Colonel Charles Trench of MacArthur’s HQ.

Two days later the 511th’s main body roared at treetop level over the Kanto Plain (where they and Eighth Army had been scheduled to fight during the invasion) and the paratroopers’ trained eyes noticed the anti-aircraft emplacements that could easily blow them out of the sky.

Fortunately, the Angels landed at Atsugi without incident with General Swing and his staff in the first plane. Colonel John Lackey piloted the craft with Swing sitting behind him accompanied by G-3 LTC Douglas Quandt, G-2 LTC Henry J. “Butch” Muller, and twenty-seven-year-old Colonel John “Jack” Atwood the Division’s Signal Officer. Prior to departure, Atwood had traveled to Manila where General MacArthur’s own Chief Signal Officer questioned Jack’s youthful age before telling him that the Angels would oversee communications for 8th Army HQ in Yokohama as well as MacArthur’s staff. As such, members of the 511th Airborne Signal Company rode in the Angels’ second plane and quickly established communications with Allied command once they landed.

Of their initial landing, Captain Stephen Cavanaugh, XO of 1/511, noted, “The Japanese commander of the field assured us that the field had been secured by his forces against any attacks by a few fanatical Japanese Army units that refused to obey the Emperor’s orders to surrender. Not taking his word, we proceeded to establish our own security and covered the arrival of Division elements as they landed.”

When the Japanese greeting delegation first approached him with swords at their sides, General Swing, who had seen too many of his men hacked by such enemy swords, growled, "Get those cake-slicers or whatever-they-are in a pile on the ground without any more delay.”

The Japanese sheepishly obeyed.

Also traveling in the flight (Baker 60) with Swing and Cavanaugh, the 511th’s Colonel Edward Lahti selected war correspondent Don Munson of Palm Beach, Florida, to go with him. In truth Don was more or less “attached” to the 511th’s HQ, but his was a coveted honor as a longing to be “the first in Japan” infected soldiers and reporters across the Pacific. Every Angel was proud that CINCAFPAC (Macarthur) had designated the 11th Airborne to lay claim to that historic achievement and since the division was making headlines around the world, Munson was looking forward to writing more of them.

Not having much to do on the ground at Atsugi, however, Don and correspondent Pfc. Frank G. Kiddoo, Jr. “acquired” a ride into Tokyo, five days before General MacArthur entered the city himself. As the capital had been declared off-limits, the two journalists wisely kept their Tokyo “tour” quiet until after the notoriously jealous general declared his own triumphal entry.

One group that did have much to do at Atsugi was General MacArthur's Honor Guard. While the 511th PIR's main body formed a perimeter around the airfield, this elite group of troopers were charged with guarding MacArthur himself once he touched down just a few hours after their own arrival (and only two hours after General Robert Eichelberger landed).

Almost two months earlier, while the 511th PIR was still outside Lipa on Luzon, General MacArthur asked General Swing to form part of his Honor Guard for Japan from the 11th Airborne. Swing passed word to his regimental commanders and Colonel Lahti of the 511th PIR ordered his company commanders to select their best paratroopers for the duty, with the stipulation that each trooper must be over 5’11”.

The 511th PIR supplied one platoon of five squads led by two officers with sixty-six enlisted men that would guard MacArthur during the surrender signings, at his Yokohama HQ (the five-story New Grand Hotel), and his home at the U.S. Embassy. And while it sounded like a ceremonial position, there were still fanatical Japanese soldiers and civilians who wanted nothing more than to see their enemy’s Supreme Commander dead, or the surrender ceremony disrupted. As such, the Honor Guard took their responsibilities seriously.

Col. Lahti’s 68 handpicked paratroopers had been awarded a combined total of over 400 medals, badges and ribbons and would be led by my grandfather’s friend, one of the original “New Guinea Wolves” 1LT Ralph Ermatinger of Fox Company and the battlefield-commissioned 2LT James C. Watkins of George Company. The officers were assisted by Platoon Sergeant and Distinguished Service Cross-recipient Sgt. Edward L. Reed of Charlie Company with Pfcs. Harry A. Swan and Robert Wilms acting as runners.

The 511th’s platoon joined the complete 11th Airborne Honor Guard under Maj. Tom Mesereau, the All-American tackle from West Point who was 6’3” and tipped the scales at 220-pounds. General Swing wrote, “He should make the brass hats appear rather colorless in comparison.”

At 1419, eight hours after Swing landed, General MacArthur’s converted C-54 Bataan touched down at Atsugi amid great fanfare. Lt. Ermatinger and the 511th’s Honor Guard moved to stand under the craft’s wings and watched the corncob pipe-carrying, sunglasses-wearing general greet Swing and the 11th Airborne Band on the tarmac. After the Angels played several numbers, MacArthur said to Warrant Officer Robert Bergland, “I want you to tell the band that that’s about the sweetest music I’ve ever heard.”

At 1419, eight hours after Swing landed, General MacArthur’s converted C-54 Bataan touched down at Atsugi amid great fanfare. Lt. Ermatinger and the 511th’s Honor Guard moved to stand under the craft’s wings and watched the corncob pipe-carrying, sunglasses-wearing general greet Swing and the 11th Airborne Band on the tarmac. After the Angels played several numbers, MacArthur said to Warrant Officer Robert Bergland, “I want you to tell the band that that’s about the sweetest music I’ve ever heard.”

The ramrod-backed paratroopers watched the helmet-wearing Swing pose for photos with MacArthur and his staff. With a smile, MacArthur turned to General Eichelberger, under whom the Angels fought on Luzon, saying, “Well, Bob, it has been a long, hard road from Melbourne to Tokyo but as they say in the movies, this is the payoff.”

After addressing the gathered troops, reporters and Japanese, MacArthur winked at the Angels’ Honor Guard before stepping into an old Lincoln with Gen. Eichelberger to head to Yokohama’s New Grand Hotel, fifteen miles away. The Honor Guard and 500 paratroopers of the 511th escorted the convoy of Japanese vehicles with a red fire engine in the lead that kept breaking down.

While General MacArthur settled in, his Honor Guard of Angels dined outside the New Grand Hotel on field rations (MacArthur enjoyed steak in the hotel dining room. When someone suggested he have the food checked for poison, MacArthur laughed and replied, “This is a good steak, and I don’t intend to share it with anyone!”)

Lt. Ralph Ermatinger, CO of the 511th’s Honor Guard noted, “Upon arrival at the New Grand Hotel, the Honor Guard took up positions at all points of entry to the building. In addition two men were posted for two-hour intervals, 24 hours a day, outside the door of the General’s suite.”

During the next evening’s dinner (August 31, Z+1), an aide announced the presence of Gen. Jonathan Wainwright who had stayed to command Corregidor’s defenses after President Roosevelt ordered MacArthur to Australia in 1942. Lt. Ermatinger watched the frail Wainwright enter the room and lean on a cane that MacArthur had given him before the war. Wainwright spent three years as a POW believing that he was seen as a failure in the States due to his surrender, but rising to great his old friend, MacArthur warmly explained to the general that he was viewed as a hero, adding, “Why, Jim, your old corps is yours when you want it.”

A moved Wainwright managed to whisper, “General…”

Surrender Ceremony onboard the USS Missouri

The next day (September 1, Z+2), the 58,000-ton USS Missouri (BB-63) sailed into Tokyo Bay at dusk with Vice Admiral Stuart “Sunshine” Murray in command. As America’s newest (and last) commissioned battleship the “Mighty Mo” carried an impressive nine 16-inch guns, twenty 5-inchers, eighty 40mm and forty-nine 20mm. Adm. Murray kept his crew busy in the early hours of September 2 (D+3) preparing for one of modern history’s most significant moments: the signing of the Instrument of Surrender.

The next day (September 1, Z+2), the 58,000-ton USS Missouri (BB-63) sailed into Tokyo Bay at dusk with Vice Admiral Stuart “Sunshine” Murray in command. As America’s newest (and last) commissioned battleship the “Mighty Mo” carried an impressive nine 16-inch guns, twenty 5-inchers, eighty 40mm and forty-nine 20mm. Adm. Murray kept his crew busy in the early hours of September 2 (D+3) preparing for one of modern history’s most significant moments: the signing of the Instrument of Surrender.

In those same morning hours, under a cloudy sky the 11th Airborne Honor Guard marched, M1s in hand, onto the Yokohama docks where dignitaries would soon board three destroyers for the forty-minute voyage to the Missouri. The 200 Angels stood ram-rod straight in polished helmets and saluted as official after official in “cars with stars” rolled down the dock while the division band played, giving “them the works” according to General Swing.

When Commanding General, U.S. Army Ground Forces General Joseph “Vinegar Joe” Stillwell arrived, he looked over the 11th’s Airborne’s Honor Guard and noticed Colonel Ed Lahti nearby. Stillwell, who had reviewed the Angels on Luzon, walked over and said, “Lahti, glad to see you and the 511th are still doing well.”

And not only doing well, they were charged with guarding one of modern history’s most important events. While the Angels’ Honor Guard was close to the action, the rest of the regiment was patrolling and guarding the docks.

General Swing himself was onboard the Missouri and watched the proceedings unfold under General MacArthur's direction. Swing later wrote to his daughter Mary Ann, “It was a most impressive ceremony, and General MacArthur handled it in a most impressive manner.” He then added of the 11th’s Honor Guard, “Your little paratrooper boys looked a million and everybody was nice enough to say so.”

For the detail-conscientious reader, Swing stood on the second row back from the table, nearly in line with the signing chair set up for the Japanese delegates. To his right stood Generals “Uncle Joe” Stillwell, Walter Krueger, Ennis Whitehead, Arthur Percival and Jonathan Wainwright. To his left stood Generals George Kenney, Harry Hodges, Robert Eichelberger and James “Jimmy” Doolittle.

After General MacArthur proclaimed the ceremony over, one of Swing's paratroopers received a fair share of the attention,though his position is rarely mentioned by authors and historians. Standing near General Swing onboard the Missouri, the 6’3” Major Tom Mesereau had a briefcase handcuffed to his wrist to carry the surrender documents back to Washington. The transfer was captured by several photographers and film crews and concerns grew that the publicity could lead to danger for Tom’s voyage. The choice was made for the Navy to smuggle the real documents off the Mighty Mo while Major Mesereau carried dummy papers down the gangplank to accompany the pictures, movies and sound recordings of the historic event back to Washington instead.

We should note, however, that Mesereau’s was not the first name submitted for the position. When General Swing met with the commanding officers of the 511th PIR, 187th GIR and 188th PIR to ask for recommendations, Colonel Ed Lahti nominated 1st Battalion’s Captain Stephen Cavanaugh to carry the documents to Washington, D.C. For reasons known only to Swing (perhaps because Rusty was so emaciated from combat conditions), Mesereau was selected.

Who Are You People

While Mesereau made his way towards the airfield, General Swing returned to the Yokohama pier where he disembarked just as transports for 1st Calvary, the Angels’ old rivals from Luzon, were coming in. Swing grinned when he saw the 11th Airborne Honor Guard waiting on the docks with large signs that read:

While Mesereau made his way towards the airfield, General Swing returned to the Yokohama pier where he disembarked just as transports for 1st Calvary, the Angels’ old rivals from Luzon, were coming in. Swing grinned when he saw the 11th Airborne Honor Guard waiting on the docks with large signs that read:

Welcome to Japan

Compliments of the

511th Parcht Inf Regt

I imagine The Old Man laughed when WO Robert Bergland had the Angels’ band strike up the song “The Old Grey Mare Ain’t What She Used to Be” to remind 1st Calvary who beat them to Japan (some in 1st Cav almost broke ranks in anger). The CO of 1st Calvary’s landing party was not amused, and Easy Company’s Pfc. John Jones of General MacArthur's Honor Guard watched him yell at every band member and paratrooper he could find.

The very Angels he was cursing would soon stand guard outside MacArthur’s HQ and home under the command of HQ1’s Cpt. Charles R. Barrett who made 130 jumps before he joined the 511th PIR on Leyte.

Things with 1st Cav didn’t end there, though. When a 1st Calvary colonel approached H-511’s blockade at the Yokohama brewery (which General MacArthur’s HQ had ordered them to guard), the cavalry officer ordered the paratroopers off the road. H Company’s Sgt. Laverl D. Pierson declined, saying his orders were to prevent any American from entering the facility. When the colonel tried to press the issue, Pierson flipped the safety off his Thompson.

“Who are you people?!” the incensed calvaryman cried out.

“The 511th Infantry from the 11th Airborne Division,” Pierson responded proudly. When the officer smugly declared that 1st Calvary was the first unit in Japan, Pierson corrected him. “We have been here for four days.”

“Sergeant,” the red-faced colonel growled, “don’t you salute a superior officer?”

“Yes sir,” Pierson replied. “But you don’t have jump wings on your shirt.”

Chewed Out by General MacArthur

The next day, September 3 (Z+4), the 11th Airborne’s twenty-three-year-old Lieutenant Bernard “Bud” Stapleton of Syracuse, NY, and photographer Captain Morton Sontheimer of San Francisco, CA decided to head into off-limits Tokyo “on a lark” to poke the bear.

The next day, September 3 (Z+4), the 11th Airborne’s twenty-three-year-old Lieutenant Bernard “Bud” Stapleton of Syracuse, NY, and photographer Captain Morton Sontheimer of San Francisco, CA decided to head into off-limits Tokyo “on a lark” to poke the bear.

“Our first stunt was to walk around the Tokyo streets unarmed,” Sontheimer reported. “Just to see what the people would do. They stared after us for blocks and when we went into a department store all business in the place stopped. We pretended not to notice, but, of course, it was a great show.”

After studying all the Japanese flags in the city, the two Angels decided to act and climbed to the top of the Nippon News Building. Stapleton, a former radio announcer, then raised the first American flag over Tokyo as Sontheimer used his camera to record the moment. Sontheimer then sent the photo to military censors, leaving his own name out of it but identifying Stapleton. The image appeared on the front page of nearly every newspaper in the country and while the Queen of England sent Bud a letter regarding the historic moment, General MacArthur,who felt the Angels had upstaged his own planned entrance with flag-raising into the city, was far less pleased and summoned the Angel for a “chat”.

“You cannot imagine what it is like to be chewed out by a five-star general,” Stapleton deadpanned.

On September 8 (Z+9), General Swing invited the 511th’s Colonel Ed Lahti to join him for a flight over Yokohama, Kawasaki, then Tokyo itself to watch 1st Calvary move in. From separate liaison planes, the Angels studied the Imperial Palace from above while down below General MacArthur made his official entrance into Tokyo where he ordered the same American flag that had flown over Washington, D.C. on December 7, 1941, be unfurled at the U.S. Embassy, his new HQ.

The Angels know who had gotten there first.

Stealing MacArthur’s Dinner

After General MacArthur made his official entry into Tokyo, his 11th Airborne Honor Guard was relieved the duties were returned to the 350th Antiaircraft Artillery. Before being released, however, the paratroopers were given one last Yokohama task: help load the general’s food stores and kitchen for the drive into Tokyo.

After MacArthur’s chef pulled a truck up to the New Grand Hotel, the Angels carried out boxes of Campbell’s soup, caviar, sausages, vegetables and other foods they had not seen in over a year. While the mess sergeant directed them to load boxes, he failed to notice the resourceful Angels “liberating” several crates by passing MacArthur’s stores over the side to their comrades.

“General Swing’s Thieves”, indeed.

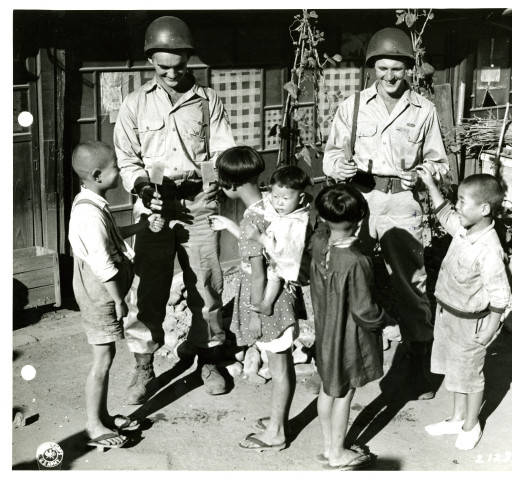

That is not to say that the Angels faded into the limelight. In fact, after General MacArthur setup shop in Tokyo's Dai Ichi Insurance building, the 511th PIR's B Company was tasked with guarding the Imperial Palace just across the street. Let other units take over responsibility for the Napoleon of Luzon; only the 11th Airborne Angels could handle guarding the Emperor and his family.

That is not to say that the Angels faded into the limelight. In fact, after General MacArthur setup shop in Tokyo's Dai Ichi Insurance building, the 511th PIR's B Company was tasked with guarding the Imperial Palace just across the street. Let other units take over responsibility for the Napoleon of Luzon; only the 11th Airborne Angels could handle guarding the Emperor and his family.

The 11th Airborne Division would stay in Japan on occupation duty until 1949 and during that time they were, at least according to Secretary of War Robert Patterson would say, “the best representatives the nation could have…an Army of which the American nation can be proud.”

Colonel Ed Lahti wrote in 1988 to the men of the 511th, “At Camp Mackall you were called ROWDIES, of course, unjustly. Then having proved your mettle in combat you were called ANGELS. Finally, you were called AMBASSADORS FOR DEMOCRACY…”

In 1998, Takakzau Kuriyama, Japan’s Ambassador to the United States, wrote of the 511th to Colonel Lahti, “I firmly believe that your gallant peacemaking efforts have contributed tremendously to the current strong mutual reliance between the United States and Japan.”

No wonder President Ronald Reagan wrote to the men of the 511th in 1988: “Together you confronted danger and endured terrible hardships, and together you rose to the challenge; you never faltered. Many of your brothers gave their last full measure of devotion so that others might live in freedom. Your accomplishments in defense of liberty will never be forgotten, and America’s debt to you will remain far more than we can ever repay.”

Amen.

If you would like to learn the full history of this historic unit, you can order a signed copy of my new book, WHEN ANGELS FALL: From Toccoa to Tokyo, The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II by visiting our online store or purchasing a copy wherever books are sold.