The Raid at Los Baños: 75 Years Later

"This operation will remain in military history as a classic example of the use of airborne troops to achieve tactical surprise." -Lieutenant-General William P. Yarborough, 1989.

“I doubt that any airborne unit in the world will ever be able to rival the Los Baños prison raid. It is the textbook airborne operation for all ages and all armies.” ― General Colin Powell, former chairman, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Los Baños Raid: The 11th Airborne Division's Greatest Rescue Operation in World War II

75 years ago two incredible events occurred thousands of miles across the vast Pacific Ocean. The first took place at around noon six United States Marines raised a second, larger American flag atop Mount Suribachi, a moment that was captured in an iconic photograph by Associated Press (AP) photographer Joe Rosenthal. When AP Photograph Editor John Bodkin received the photo on Guam he exclaimed "Here's one for all time!" and immediately transmitted the image to the AP headquarters in New York City. It became one of the most recognized images from the war, indeed in American history.

The prominence of Rosenthal's photo in the press overshadowed, then and now, the accomplishment of another group of fighting men who risked it all to to rescue over 2,100 men, women and children from behind enemy lines over 1,500 miles southwest of Iwo Jima. Theirs was the second incredible event that took place on February 23, 1945 and it is as inspiring as it is impressive.

When Imperial Japanese forces invaded the Philippines in December of 1941 it began a brutal occupation of the archipelago that lasted until 1945 and the Filipino people suffered tremendously at the hands of the invaders during those years. An estimated 500,000 Filipinos were killed before the occupation was broken by Allied forces, with the cooperation of local guerrilla groups, in September of 1945.

One of the main forces battling for the liberation of Luzon in early 1945 was America's 11th Airborne Division, a unique fighting force that landed a portion of their TOE amphibiously at Nasugbu on January 31 and then the remainder on Tagaytay Ridge just south of Manila on February 3. Known as The Angels, the 11th Airborne fought up through southern Manila, breaking through the famous Genko Line, and went on to liberate Nichols Field, Fort William Mckinley, Intramuros, Cavite and several other "battlefields" in vicious engagements and close-quarters fighting that have received far too little attention from historians and both the American and Filipino peoples as a whole (which is one of the main reasons I wrote my highly-acclaimed book, "When Angels Fall: The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II - Amazon $14.95).

One of the main forces battling for the liberation of Luzon in early 1945 was America's 11th Airborne Division, a unique fighting force that landed a portion of their TOE amphibiously at Nasugbu on January 31 and then the remainder on Tagaytay Ridge just south of Manila on February 3. Known as The Angels, the 11th Airborne fought up through southern Manila, breaking through the famous Genko Line, and went on to liberate Nichols Field, Fort William Mckinley, Intramuros, Cavite and several other "battlefields" in vicious engagements and close-quarters fighting that have received far too little attention from historians and both the American and Filipino peoples as a whole (which is one of the main reasons I wrote my highly-acclaimed book, "When Angels Fall: The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment in World War II - Amazon $14.95).

In the midst of all the heavy fighting, the Angels were given another mission, or at least a directive, from General Douglas MacArthur himself who was growing increasingly concerned about the welfare of tens of thousands of POWs and interned civilians on Luzon. With the U.S. Sixth Army pushing southward from the Lingayen Gulf and Eighth Army (i.e the 11th Airborne Division) pressing north from Nasugbu, and after the massacre of 150 Allied POWs on Palawan, the consensus was that the Japanese appeared more ready to kill their prisoners than allow them to be rescued (a fear that was later confirmed with a discovered order from Japan’s Vice-minister of war LTG Kyoji Tominaga).

In his autobiographical book Reminiscences MacArthur noted: “I hoped to proceed as rapidly as possible, especially as time was an element connected with the release of our prisoners.… I knew that many of these half-starved and ill-treated people would die unless we rescued them promptly.”

With the successful liberation raids effected on Cabanatuan, Santo Thomas and Bilibid Prison in the first six weeks of 1945, attention was turned roughly 40 miles southeast of Manila to the southern tip of Laguna de Bay where the Los Baños Internment Camp sat on the University of the Philippines Agricultural School grounds.

There roughly 2,150 men, women and children had been languishing as prisoners of the Japanese, many since December of 1942, roughly three and a half years. They were not soldiers, but rather everyday businessmen, mechanics, teachers, bankers, nuns, priests, missionaries and wives and children of military personnel. Eleven were Navy nurses known as the “Angels of Bataan” and these "Sacred Eleven" had a first-hand view of the effects of their captors' inhumane methods of torture, abuse and starvation under the roughly thirty-year-old Lt. Sadaaki Konishi, the camp’s cruel second in command who proudly declared that he hated all Caucasians.

When I asked my friend Robert A. Wheeler, who was just a boy when his family was sent to Los Baños, about Konishi, Bob growled, "I would describe Konishi as a sadist and terribly mean." (I highly recommend reading Bob's book, "A Child's Life: Interrupted by the Imperial Japanese Army" - Amazon $15)

After months of woe, the internees were starting to die. By January of 1945, Konishi had reduced the prisoners’ diet to less than 450 calories a day, roughly the equivalent to three modern granola bars which led one of the camp's many Catholic priests to soberly declare, “If we’re going to get out of this alive, we better pray.”

A faithful nun replied, “If we’re going to get out of this alive, God will have to send the angels.”

He would. The Angels were coming.

The Angels

The 11th Airborne's Major General Joseph May Swing (far right without helmet) had been made aware of the Los Baños internment camp by Eighth Army’s Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger (second from left) on February 12. However, due to his division's heavy engagements with the Japanese in Southern Manila, Swing asked XIV Corp’s Gen. Oscar Griswold if the Angels could postpone the mission for a short time. Griswold agreed, but told Swing to effect the rescue as soon as a force of sufficient size could be spared from the vicious fight for Manila.

The 11th Airborne's Major General Joseph May Swing (far right without helmet) had been made aware of the Los Baños internment camp by Eighth Army’s Gen. Robert L. Eichelberger (second from left) on February 12. However, due to his division's heavy engagements with the Japanese in Southern Manila, Swing asked XIV Corp’s Gen. Oscar Griswold if the Angels could postpone the mission for a short time. Griswold agreed, but told Swing to effect the rescue as soon as a force of sufficient size could be spared from the vicious fight for Manila.

In the meantime, Swing's G-2 (Intelligence) LTC Henry J. “Butch” Muller, Jr., who first heard about Los Baños before New Years when a grower from Mindanao reported that the internees were being treated terribly, had his staff gather intelligence on the camp to prepare for the future operation. In addition to reconnaissance flights and utilizing the division's own reconnaissance platoon (or "Ghost Platoon") much of the information came from Col. Jay D. Vanderpool’s guerrilla forces who began watching Los Baños in early February. Vanderpool’s CP was across the street from Gens. Eichelberger’s and Swing’s respective HQs in Parañaque which allowed for easy coordination. Vanderpool and Eichelberger ate together on February 8 and the two discussed the feasibility of using Filipinos to affect the rescue, an action Vanderpool (whom the Angels affectionately called “The Little Corporal”) believed was impracticable. Vanderpool's demurral of Eichelberger's inquiry most certainly led to the general passing the mission to Gen. Swing's 11th Airborne Division which was busy with heavy fighting south of Manila and around Nichols Field and Fort William McKinley.

Vanderpool did, however, order local guerrilla forces to prepare for such an operation if a massacre seemed imminent which is exactly what Col. W. C. Price of the President Quezon’s Own Guerrillas (PQOG) reported to Vanderpool a short time later. The guerrillas reported that local laborers had been paid by the Japanese to dig a large trench at Los Baños which alarmed both the Filipinos and the Americans as the trench could easily be used as a mass grave should the Japanese massacre the internees. Gen. Swing's "Angels" would have to act soon; rumor had it that the enemy was going to do exactly that on February 23.

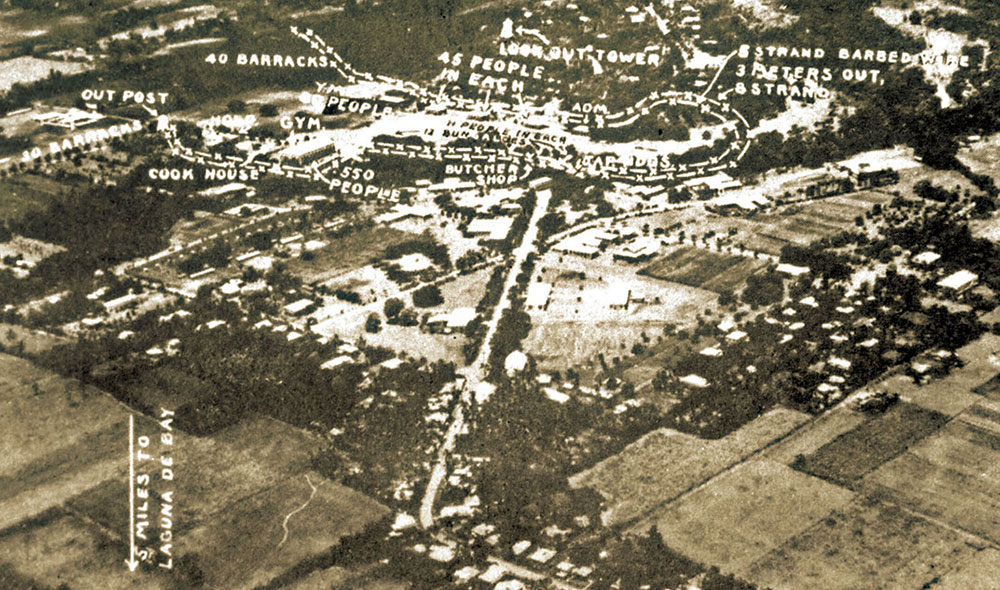

Their operation had been in the planning stages under Swing's G-3 (Operations), the thirty year-old Colonel Douglas P. Quandt whose staff had been working out the logistics of how to reach the camp itself, eliminate the Japanese guards, then evacuate all the internees and rescuers safely. Quandt and LTC Muller would benefit greatly from meeting with escaped internee Peter Miles, a civilian engineer who snuck out of camp and helped the Angels put the finishing touches on their operation with a map of enemy positions and defenses plus a description of the daily schedules of the camp. One key piece of intel that Peter shared involved the guards' calisthenics routine; at 0700 many of the Japanese locked their rifles away while exercising which gave the Angels a slim window of golden opportunity to strike.

After input from Gen. Swing, the plan was submitted to Gen. Oscar Griswold who heartily approved. The question remained, however, which company of Swing's paratroopers had the manpower to effect the raid.

The Mission

The 511th Parachute Infantry Unit was the first official unit to form in Swing's 11th Airborne Division at Camp Mackall, North Carolina, in March of 1943. While the proud and cocky paratroopers had given "General Joe" plenty of headaches during their stateside training and then on New Guinea, the unit had fought ferociously and with distinction on Leyte during November and December of 1944. Barely given time to rest, the 511th PIR had jumped on Luzon's Tagaytay Ridge on February 3 then pushed north to engage the aforementioned enemy defenses around and throughout Manila.

What many articles and books regarding the Los Baños operation fail to point out is that this means the Angels had only been in-country for three weeks when they jumped on Los Baños. And during those three weeks, the 511th suffered terrible losses even as they won victory after victory on the battlefield. To give you an idea, my grandfather's company commander Captain Steven "Rusty" Cavanaugh noted, “Between the 5th and the 10th of February D Company sustained thirty-eight men killed or wounded. This was almost a third of the company strength...”

And they were lucky; some companies in the regiment were approaching 70% casualties. When Nichols Field was declared secure on February 12 (13 days before the raid), H Company’s original compliment of 121 was down to just 49. As such, when Gen. Swing sent 2LT Bill Abernathy, the 511th’s liaison with Division HQ, to LTC Edward Lahti’s CP on February 21 with a handwritten order regarding the Los Baños mission, Lahti asked Regimental Personnel Officer Cpt. Robert T. Foss which company had the greatest strength available. Foss indicated that Baker Company had a strength of about 80 men, but 1st Battalion's Major Henry "Hank" Burgess later decided to augment the combat team with a light machine gun platoon from HQ1 under 2LT Walter Hettlinger. Burgess was concerned that Japanese forces in the area could move in during the raid before the Angels’ main force arrived and he wanted the extra firepower with his men.

Worried about the operation, Burgess asked himself, "How could my force of 412 paratroopers slip undetected deep into Japanese-controlled territory, wipe out a large number of enemy guards at the camp before they could kill the inmates, and bring back to safety, 2,200 weak men, women, and children, many of whom were unable to walk?”

It is of note that at just thirty-one years of age, Colonel Lahti himself was likely the youngest regimental commander in the U.S. Army after he took over for the legendary Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen who had been seriously wounded in the chest on February 12. Lahti, the West Point graduate, went to track down B Company's commander, 1LT John Ringler. Ringler had only been in command since mid-January and "Slugger" found the twenty-six-year-old officer and barked, "You will report to the Division Commanding General and I will take you there."

The order gave Ringler some pause. He later noted, "Anytime a Major General wants a Lieutenant to come up, you’re going to get relieved; you did something wrong.”

But Ringler wasn't in trouble, at least not the kind he was fearing. At General Swing's CP he encountered LTC Muller (G-2) and Colonel Quandt (G-3) who announced to Swing that "This is the lieutenant that’s going to have the mission." The introduction piqued Ringler's already-high interest and "The Old Man" proceeded to explain the rescue operation to the young lieutenant (you can see an aerial shot of the camp to the right). Ringler, who retired a full-bird Colonel after Vietnam, later wrote, "That’s the first time in my military career that a division commander, a major general, gave a mission to a lieutenant company commander."

But Ringler wasn't in trouble, at least not the kind he was fearing. At General Swing's CP he encountered LTC Muller (G-2) and Colonel Quandt (G-3) who announced to Swing that "This is the lieutenant that’s going to have the mission." The introduction piqued Ringler's already-high interest and "The Old Man" proceeded to explain the rescue operation to the young lieutenant (you can see an aerial shot of the camp to the right). Ringler, who retired a full-bird Colonel after Vietnam, later wrote, "That’s the first time in my military career that a division commander, a major general, gave a mission to a lieutenant company commander."

Johnny added that Swing “emphasized to me that unless we were successful, we may have problems getting out of the area and would be engaged in heavy fighting.” Ringler, Swing, Lahti, Muller and Quandt all understood the risk: B Company could could potentially be cut off and suffer severe casualties defending the civilian internees before help arrived (or both groups could be destroyed completely).

Even so, neither Ringler nor B Company wavered in their willingness to go. After John informed his company of their mission once they had been trucked to Bilibid Prison, he noted, "Everyone had the attitude, ‘It not only can be done, it will be done.'"

Things became more "real" as the briefings progressed, however. While their belief that they could pull of the mission never wavered, Lieutenant Ringler remembered, "I don’t believe that they initially understood the full danger of the mission until after our briefings were completed. At that time they became apprehensive of what could happen; however, with the amount of intelligence that we had we were very confident of success. We realized that we might be dropping into a hornet’s nest, which could result in considerable casualties. Regardless of our feelings, we knew that the mission was ours to accomplish. This was truly an ideal airborne mission, and this is what we were trained for."

B Company spent the night of February 22 at Nichols Field, sleeping under nine C-47s of the 75th Trooper Carrier Squadron on their parachutes under a moonless Pacific sky.

The Plan

With B Company preparing for their historic jump, the division's Provisional Reconnaissance Platoon under Lt. George Skau left to mark the paratroopers' drop zone with smoke and to eliminate the camp's guards at H-Hour. Known as The Ghost Platoon, Skau's men crossed Laguna de Bay in native bancas in a harrowing trip that risked detection by Japanese patrol boats (Skau's men crouched low in the bancas, weapons at the ready just in case). The Angels arrived early on February 22 and in the cover of darkness they crept through rice paddies to the camp, a journey that took about ten hours.

When they arrived at the camp, Skau's men and their guerrilla compatriots silently moved to their stations around the camp to await the sign of the first parachute at H-Hour (small teams of scouts also marked B Company's dropzone with smoke grenades as well as the landing beaches).

Another piece of the operation that moved quite a bit less stealthily was the 54 Amtracs of the 672nd Amphibian Tractor Battalion that would depart Mamatid and cross Laguna de Bay strictly by compass early on February 23 beginning at 0515. Under the command of LTC Joseph W. Gibbs, the Amtracs would carry the 511th's A and C Companies as well as select units from the 127th Airborne Engineer Battalion and the two 75mm pack howitzers with crews from D Battery 457th Parachute Field Artillery Battalion under Captain Luis Burris. This combined unit would land at Mayondon Point near San Antonio which was marked by a recon squad under Sgt. Leonard Hahnand before the Amtracs drove the two miles to the camp.

The Angels planners still had to contend with the enemy's numerically superior forces in the surrounding areas, especially the 8,000-10,000 troops of Japan’s 8th “Tiger” Division under the command of Lt. Gen. Masatoshi Fujishige who were camped just across the San Juan River and could reach the camp within three to four hours. In addition to various other small enemy units, numerous Filipino Makapali, or enemy conspirators the Angels called “Brown Japs”, were in the area and could alert the Japanese or provide interference.

To pull the enemy's attention in another direction, the Angels would send the 188th Glider Infantry Regiment (less 2nd Battalion), C Company of the 637th Tank Destroyer Battalion and select units of the 472nd and 675th Field Artillery Battalions to engage the enemy. Under the command of Col. Robert H. Soule, “Task Force Soule” would move down Highway 1 as a diversion and, if needed, block the Japanese from disrupting the rescue.

We should note that Gen. Swing fully intended to participate in the raid by riding in one of the Amtracs. While at Mamatid, late on February 22 Maj. Henry Burgess sent 1LT Robert “Bob” S. Beightler, Jr., back to Swing’s HQ to pick up the general in a Jeep. Given the late hour, Beightler, his driver and Swing drove on dark unfamiliar back roads with headlights blacked out. Both Beightler and his driver could sense Swing’s growing frustration that they had not yet reached their destination, Mamatid. When the Jeep slammed to a halt three feet from the edge of a deep gorge whose bridge had been blown, Swing’s temper blew as well.

Beightler later commented during a speech to his comrades on November 20, 1988, “I have never ever seen a man quite so mad, before or since. At that moment I wished I had gone over the cliff.”

"They've Come!"

Early on February 23, 1945, the tired, weak and hungry internees at Los Baños gathered in the pre-dawn mist for roll-call then watched the guards assemble in just their loincloths for morning exercises, or radyo taisyo. As the Japanese shouted "Long live the Emperor!", the internees ate watery rice soup or porridge and wondered silently just how much longer they would live. Mothers looked at their children, husbands their wives. Priests, nuns and missionaries prayed and the gamblers and prostitutes in the camp, well... February 23 was shaping up to be just another day in Los Baños until at three minutes to 0700 a shot rang out outside the camp's double barbed-wire fences.

Lt. George Skau's recon platoon and their accompanying Filipino guerrillas froze. A Japanese sentry had fired on some animal, possibly a hedgehog, he had seen, barely missing one of the guerrillas who was hidden in the foliage. Believing that they had been spotted, Captain Marcelino Tan of the Hunter's 45th Regiment ordered a lone guerrilla to use his deadly bolo to dispatch the guard which unfortunately alerted the Japanese soldiers manning the machine gun nests and other fixed positions.

Two and a half minutes early, the Angels' scouts and their Filipino comrades opened fire on two Japanese machine gun positions, suffering three casualties in the process while several miles away and four-hundred feet above them 1LT John Ringler ordered his men to stand up and hook up. As jumpmaster for the operation, Ringler stood in the door, watching for the smoke in the Drop Zone he had selected the day before. When the greenlight lit up, Johnny kicked the equipment bag out the door and pivoted into the air while his stick of jumpers rushed after him.

When Ringler's parachute first billowed open, LT George Skau tapped the head of the scout next to him who fired on a machine gun nest with a bazooka. Inside the camp internees watched the nine C-47s disgorge their deadly cargo and as the 132 parachutes opened like popcorn in the sky, the imprisoned civilians cried out in jubilation, "They've come! They've come!"

Despite the small size of the Drop Zone, B Company with Hettlinger’s machine gun squad landed safely minus Cpl. Francis J. Flanagan who dropped onto the railroad track and was knocked out on the rail after spraining his ankle. In 1985, Maj. Henry Burgess returned to Los Baños with a handful of older troopers and walked the grounds where the camp had laid. When he reached their 1945 DZ, Hank was impressed. He wrote to LTC Edward Lahti, “When you look at the small area between the power line and the railroad, you’ve got to realize how good the 511th was to be able to put those men in such a tight area."

Prior to their jump, Lieutenant Ringler had warned his men to avoid the power lines, stating the obvious: "If you hit it, you’re fried!"

"Father, Let's Get the Hell Out of Here"

On the ground, B Company shed their parachutes, assembled on their platoon leaders, then rushed towards the camp, eliminating a machine nest on the way. The paratroopers joined LT Skau's recon platoon and a few guerrillas in eliminating or chasing off the remaining Japanese guards while the frightened internees crouched low in their quarters as bullets zipped through the walls overhead. Many continued eating their breakfasts while S. Davis Winship reportedly continued to shave despite the chaos around him.

1LT Ringler later wrote, “One point of the operation that I have never understood is how could you have over two thousand persons in the target area and live fire coming in from four sides and yet not have a casualty within the camp. It is actions like this that makes us think of Who controls our destiny.”

Lewis Thomas Watty, vice president of the camp's POW committee, remembered, "The ensuing fight went on for very long minutes without letup, enemy defenders caught by total surprise were pinned and cut down mercilessly by liberator’s fire."

Internee Gilbert L. Wells remembered watching one of the paratrooper carefully sneak up to an enemy position with five Japanese in it. The paratrooper tossed in a grenade and unloaded his Thompson machine gun before trotting over to a group of cowering internees and inquired, “Any chance of a cup of coffee around here?"

After roughly twenty minutes, the sounds of combat began to fade and Ringler’s men rushed through the camp, urging the internees to gather their belongings and prepare for departure. Internee Carol Terry Talbot wrote, “suddenly appearing from somewhere, a towering giant loomed over me. Clad in olive-drab green, with a large helmet on his head, boots on his feet, and a gun in his hand, he looked like someone from another world… (His) voice was not gentle and soft, but strong, pressured, urgent, and compelling in its intensity, ‘Lady, you’ve got five minutes to get into an Amtrac.’”

In the summer of 1944, while the 11th Airborne Division had been training in Dobodura, New Guinea, the Japanese on Luzon rounded up three hundred Catholic priests and nuns and additional clergy and transferred them to Los Baños. Their section of camp was dubbed “Vatican City” while the rest of the enclosure was “Hell’s Half-Acre.” With that many clergy, no wonder Los Baños had more than 130 Masses each day in their improvised “chapel.”

Sister Louise Kroeger, one of the many nuns in the camp, wrote of her first encounter with the B Company troopers, “We thought each soldier an angel, and a giant one at that. They were massive compared to our malnourished men in camp.”

Sister Maria del Rey Danforth remembered the Angel who rushed into their quarters and said, “Won’t my mother be proud when I tell her I rescued the sisters!”

When another trooper rushed into one of the female barracks, he was surprised when a woman asked if he was a Marine. Answering in the negative, she then said, “All my days at Los Baños I have dreamed of being rescued by a Marine. And you’re not a Marine.” The Angel helped her anyway.

As Navy Lt. Dorothy S. Danner, one of Los Baños’ “Sacred Eleven” nurses (pictured to the right with Admiral Thomas H. Kincaid after the raid), was assisting a new mother and her baby, she looked up as, “(T)he Amtracs came in, crashing through the swali-covered fence near the front gate.” The Alligators had arrived, although most had to wait outside the camp on the baseball field and other open areas as to avoid a traffic jam. The large vehicles caused momentary panic for some internees who thought their loud 250 horsepower Continental engines belonged to Japanese armor (some internees even thought their white stars signaled that they had been rescued by the Russians).

As Navy Lt. Dorothy S. Danner, one of Los Baños’ “Sacred Eleven” nurses (pictured to the right with Admiral Thomas H. Kincaid after the raid), was assisting a new mother and her baby, she looked up as, “(T)he Amtracs came in, crashing through the swali-covered fence near the front gate.” The Alligators had arrived, although most had to wait outside the camp on the baseball field and other open areas as to avoid a traffic jam. The large vehicles caused momentary panic for some internees who thought their loud 250 horsepower Continental engines belonged to Japanese armor (some internees even thought their white stars signaled that they had been rescued by the Russians).

“Enemy tanks!” someone shouted and B Company and the recon scouts in the area immediately returned to alert status before the all clear was sounded. Upon seeing the white stars on the sides of the Amtracs, 2,142* internees cried tears of joy and hugged their rescuers. Many of the priests and nuns fell to their knees to thank God. One trooper put a hand on minister’s shoulder and said, “Come on, Father; let’s get the hell out of here.” They did, together.

“How kind and courteous they were,” remembered Sister Maria del Ray Danforth. “Circumstances could easily have pardoned gruffness or severity, but no, every soldier was as good humored, even suave, as a department store salesman.”

One prisoner shouted, “Thank God for the paratroopers.… These are the angels He sent to save us!”

*This number is the most accurate total as Carol Talbot/Muirs, who took roll in the camp, gave a final tally of 2,147 several days before the raid. In the ensuing days, six people died and one baby was born, Lois, so the correct number of rescued internees is 2,142.

An Impossible Task

Major Henry Burgess dismounted from his Amtrac and, after assuming command of all the Angels' forces, at 0745 Burgess found Lt. Ringler and discussed the need to evacuate the camp. There was still a very real threat from enemy units in the area as Japan’s 8th “Tiger” Division was camped just seven miles away. One battalion was quartered near Alaminos, a mere 90-minutes away so if the enemy was already on the move, everyone had to get out now.

Unfortunately, the now-free men, women and children of Los Baños were more interested in celebrating than departing (some even refused to move until they had finished their tea). As Ringler later wrote, “…the internees were very jubilant and excited as to the events taking place… Trying to control them and keeping them in one place was almost an impossible task.”

One liberated American cried out, “Oh, God, it’s been a long time we have waited for just such Hollywood American stuff.” (take note of her words, Hollywood).

After a Filipino guerrilla dropped a grenade in a drainpipe to kill an enemy guard hiding therein, Major Burgess decided to get things moving. After noticing that the celebrating internees were migrating away from a burning building he told 1LT Ringler to take some men and to begin burning the internees' barracks to force them to head for the Amtracs (Burgess sent 2LT Hettlinger and some of his machine gun squad to complete the task). It may seem like a cold tactic to modern readers, but for the Angels and the internees, time was something they were running out of. Although A and C Companies of the 511th PIR were in position to block approaches to the camp, Major Burgess received a report that a large Japanese force seemed to be preparing to attack.

Luckily the burning buildings did the trick. Major Burgess noted, “The results were spectacular. Internees poured out and into the loading area. Troops started clearing the barracks in advance of the fire and carried out to the loading area over 130 people who were too weak or too sick to walk.”

The troopers even carried three-day old Lois Kathleen McCoy out in a helmet liner and Los Baños was fully evacuated by 0845 and the column rode or walked back towards the beachhead at San Antonio with the leaders arriving around 1000 (Burgess elected to bring up the rear). Internee Father William R. McCarthy wrote, “Men, women and children followed, bundles under their arms or dangling from sticks, carrying their scant possessions with them…. With many others we walked over the highway of freedom against a background of flames...”

The tense situation was softened by laughter when one of the Amtracs came rumbling down the road. Loaded with nuns, the vehicle bore the self-imposed nickname of its driver’s fiancée: “Impatient Virgin”.

Withdrawal

Upon reaching the shoreline, the sympathetic troopers shared rations and the Amtrac crews distributed 10-in-1s and whatever else they could find. Unfortunately, while grateful, some internees were so emaciated that their stomachs could not handle the food and became sick. Questioning the monstrous machines’ ability to float, it took convincing to get some of the civilians onboard. The weakest internees and women and children were loaded, and the Alligators started lumbering across Laguna de Bay towards Mamatid Village carrying their precious cargo.

crews distributed 10-in-1s and whatever else they could find. Unfortunately, while grateful, some internees were so emaciated that their stomachs could not handle the food and became sick. Questioning the monstrous machines’ ability to float, it took convincing to get some of the civilians onboard. The weakest internees and women and children were loaded, and the Alligators started lumbering across Laguna de Bay towards Mamatid Village carrying their precious cargo.

Major Burgess spread his remaining forces out in a defensive perimeter and a shortwhile later C Company's Thomas Meserau reported that his men had engaged and eliminated a small enemy detachment. Time slowly ticked by until Japanese mortars began to fall near and then within the Angels' defensive perimeter, alarming the civilians and sending the paratroopers and artillerymen into high alert (Burgess also had a rather interesting conversation with General Swing via the artillerymen's radio).

Japanese machine gun fire kept the Angels' heads down until finally after noon Col. Gibbs and his Amtracs returned after 1200 and Burgess had the last internees load first, then the guncrews of the 457th PFAB and finally his own paratroopers just as several hundred of the enemy arrived. The Japanese began leap-frogging forward, firing as they came on and Amtrac gunner Art Coleman remembered, “As we entered the water, mortar and artillery fire descended on us, but not a round found its target. Major Henry Burgess later told me he could hear the Jap officers giving commands as we withdrew.”

During their return trip, the artillery men noticed a Japanese gun crew on a hillside to the west which was firing on the lumbering column of amphibious tractors (Robert Wheeler told me he remembered dropping to the deck to avoid getting hit). The 457th's Sgt. Harold “Moose” Mason recalled: "The howitzer was high enough on the pile of baggage for us to contemplate firing a round back at the hill, which was the only place we thought the firing might be coming from. So, we loaded and fired at the hill with a charge one, I believe. The machine gun stopped firing but the (Amtrac) was dipping from side to side and taking on water with each dip. The… driver pointed a .45 pistol back at us and said, ‘Anyone loading that thing again gets a bullet in the head.’”

The artillerymen wisely decided to let things be.

Mamatid

The scene at Mamatid was both touching and inspiring. The internees were met by throngs of anxious medical personnel, American soldiers and local Filipinos who loaded them into trucks and ambulances which whisked the group from the landing area to New Bilibid Prison, the very location their rescuers from B Company, 511th PIR, had stayed at two evenings prior. They had been showered with chocolate D Rations in addition to the Angels' K-Rations and cigarettes, all of which unfortunately made some of the malnourished internees sick, but they appreciated their rescuers' kindness.

My friend internee Robert Wheeler later wrote, "They were and are a special breed, those men who came that day... Superbly trained, thank God—men who went home after they served—going on with their lives—not complaining, humble, proud that they served."

At Bilibid the internees' names were checked off lists and they were served soup served from garbage cans (they were thoroughly cleaned first) which many of the liberated men, women and children partook of several times. No one said a word, especially not to former internee Frank Buckles, the World War I veteran who had been in Manila on business when Japan invaded in 1941. Buckles lost fifty pounds during his ordeal and would go on to be the last living American veteran from The Great War before he died on February 27, 2011 at the ripe old age of 110.

At Bilibid the internees' names were checked off lists and they were served soup served from garbage cans (they were thoroughly cleaned first) which many of the liberated men, women and children partook of several times. No one said a word, especially not to former internee Frank Buckles, the World War I veteran who had been in Manila on business when Japan invaded in 1941. Buckles lost fifty pounds during his ordeal and would go on to be the last living American veteran from The Great War before he died on February 27, 2011 at the ripe old age of 110.

As the internees settled in to eat, clean up, receive new clothes and generally rest from their ordeals, there was an overriding sense of exhilaration that the raid had been so successful and General Douglas MacArthur himself noted, "God was with us today and we should be thankful for all he did to help us out."

Division G-2 LTC Henry Muller Jr., later noted, “Everything that could have gone wrong didn’t go wrong. Everything that had to go right did go right. Murphy’s miserable law was suspended for 24 hours.”

The famous airborne historian Major Gerard M. Devlin echoed Muller's sentiments when he wrote in 1979, “Because of the highly accurate intelligence information, a perfect plan, and a faultless performance by the attacking troops, the Los Baños mission is still considered to be the finest example of a small-scale operation ever executed by American airborne troops. There is no doubt that it will remain a masterpiece of planning and execution and the blueprint for any future daring prisoner-rescue operation.”

Watching the scene, General Swing wrote to his father-in-law, the legendary General Peyton C. March, "You never saw such a happy crowd."

Swing also noted that the raid "would have made Knute Rockne envious in his heyday."

The internees certainly made sure to thank their rescuers, though some mistakenly thanked my grandfather 1LT Andrew Carrico's D Company men (the civilians later smiled and said B sounded like D) who were helping to guard the area. Over the next few weeks and months, the men, women and children were nourished back to full health and expatriated back home once it was deemed safe for them to do so.

Aftermath

Many of the Angels I have met with and interviewed over the years expressed deep sadness that the efforts and exploits of their mighty 11th Airborne Division have been relatively overlooked by military historians, authors, Hollywood and the American public as a whole.

That said, there are some footnotes to that "absence of attention", the first of which occurred in 2003 when the 11th Airborne Division Association created The Los Baños Liberation Memorial Scholarship Foundation which provides grants to students at the Rural High School of the University of the Philippines.

Two years later, to honor the raid’s 60th anniversary, U.S. Representative Trent Franks (R) of Arizona sponsored House Joint Resolution 18 which passed on February 16, 2005. This resolution commemorated the heroic raid and reaffirmed the nation's commitment to a full accounting of prisoners of war and those missing in action.

As Representative Franks noted:

One week later the raid was commemorated on Luzon with a ceremony held to unveil a new historical marker at the site of the former internment camp. The participants and audience included Filipino government officials and U.S. Ambassador to the Philippines Francis J. Ricciardone, Jr.

As for the Angels themselves who so effectively pulled off the raid, some were killed in later actions while most went home after the war to lead normal, yet full lives. These once young men who had swaggered the streets of Toccoa and Mackall in polished paratrooper boots became lawyers, doctors, judges, farmers, automotive salesmen, manufacturers, teachers, policemen, and so on. They treasured their wives and children and most of all they never lost their love for their country, or the Army. When asked if they would be willing to take up arms in America's defense again, even in their old age these battle-hardened troopers declared, "I'll go today if needs be."

As for the Angels themselves who so effectively pulled off the raid, some were killed in later actions while most went home after the war to lead normal, yet full lives. These once young men who had swaggered the streets of Toccoa and Mackall in polished paratrooper boots became lawyers, doctors, judges, farmers, automotive salesmen, manufacturers, teachers, policemen, and so on. They treasured their wives and children and most of all they never lost their love for their country, or the Army. When asked if they would be willing to take up arms in America's defense again, even in their old age these battle-hardened troopers declared, "I'll go today if needs be."

Perhaps my grandfather's friend 1LT Ralph E. Ermatinger of F-511 said it best: “While not being from the samurai class, none-the-less, I do recognize great warriors when I see them, and I take great pride in having served with the best fighting men of World War II.”

It surprises me very little, then, that Lieutenant General Gary E. Luck, Commanding Officer, XVIII Airborne Corps, declared, "Whenever brave soldiers meet to celebrate and pay respect to honor, fidelity, courage and sacrifice…the exploits of the 11th Airborne Division will be recounted with pride."

May we all raise a glass to toast the Angels.

To learn more about the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of our books on the Angels: