The Rat's Ass Charge is the story of one of those incredible engagements from World War II, one effected by a small, understrength and under-supported parachute companies, that equals anything that has been written about the incredible exploits of the 101st and 82nd Airborne Divisions in Europe.

That is not said to in any way to diminish what the Screaming Eagles and the All-Americans did "over there." Rather, it is only to point out that the 11th Airborne Division is equally deserving of attention, researching, illumination and praise. This is only a small piece of their story.

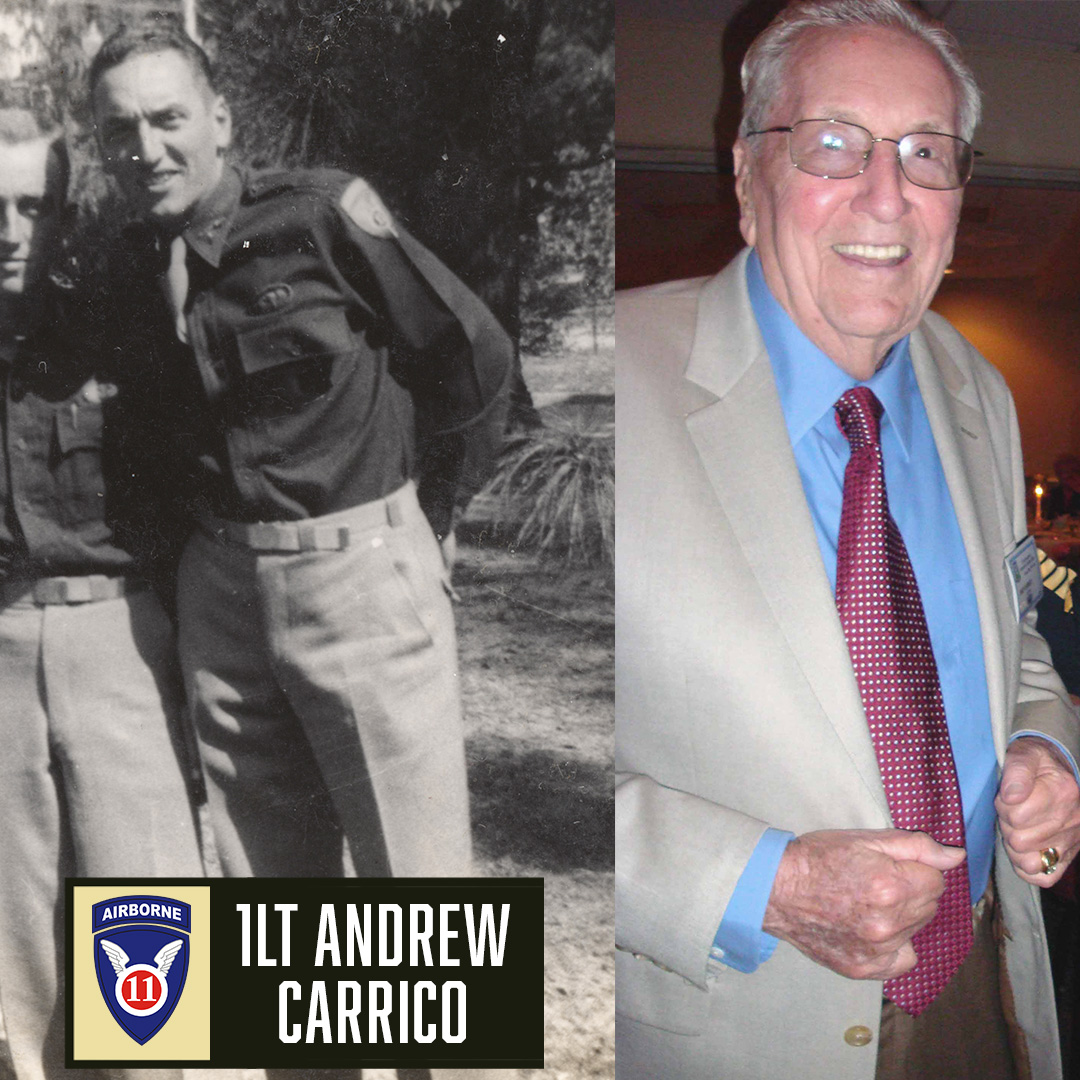

On Thanksgiving Day, 1944, after a breakfast of cold turkey and rain-soaked potatoes and fruit salad, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment led the 11th Airborne Division's push westward into the jungles and mountains of Leyte in the Pacific Theater. Over the next 30+ days, the young paratroopers of the 511th PIR would endure the harshest of conditions including hunger, thirst, cold, monsoon rains, Banzai assaults, tropical diseases, blood and death. Many companies went over five days (one up to ten) without resupply and rations and as D Company's 1LT Andrew Carrico later noted, resorted to eating "anything we could find: dogs, roots, potatoes. When you’re hungry you’ll eat anything. Hunger was a constant gnaw in our stomachs."

On Thanksgiving Day, 1944, after a breakfast of cold turkey and rain-soaked potatoes and fruit salad, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment led the 11th Airborne Division's push westward into the jungles and mountains of Leyte in the Pacific Theater. Over the next 30+ days, the young paratroopers of the 511th PIR would endure the harshest of conditions including hunger, thirst, cold, monsoon rains, Banzai assaults, tropical diseases, blood and death. Many companies went over five days (one up to ten) without resupply and rations and as D Company's 1LT Andrew Carrico later noted, resorted to eating "anything we could find: dogs, roots, potatoes. When you’re hungry you’ll eat anything. Hunger was a constant gnaw in our stomachs."

Division commander MG Joseph May Swing would later tell his father-in-law Peyton C. March that by mid-campaign, "We’ve killed over 2000 Japanese…” in what Swing called “a process of extermination...Casualties on our side are not light..."

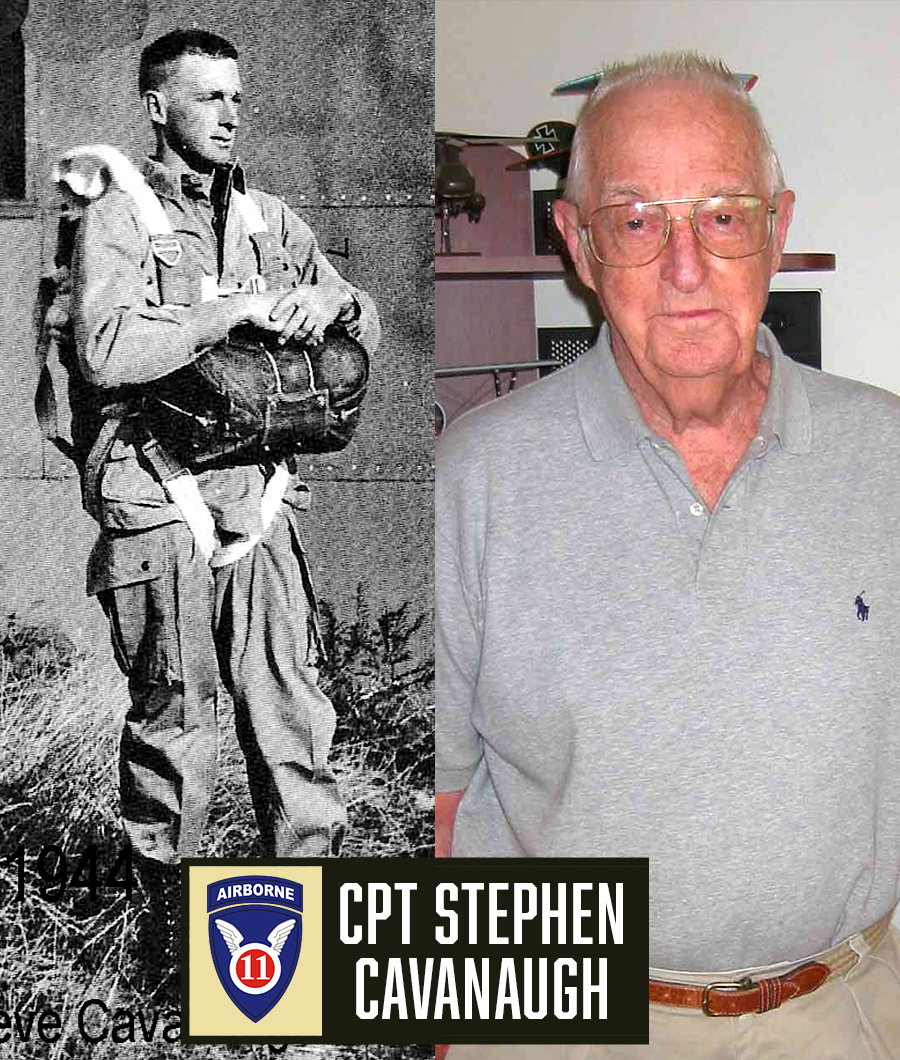

Not light indeed; the 511th PIR was down to just 60% strength, having suffered over 400 casualties in roughly three weeks, roughly 75% of the Division’s losses, while eliminating 5,760 soldiers of Japan’s 26th and 16th Infantry Divisions. When they marched down to Ormoc Bay on Leyte's western coast on Christmas Day, Captain Stephen Edward Cavanaugh explained, "We came out on the other side of the island a pretty well decimated regiment." Cavanaugh's D Company left Leyte's Bito Beach on November 23 with 117 men; twenty-one of their comrades now lay dead in the mountains or were being carried out on poncho stretchers.

The photo to the right is of the 511th PIR's cemetery on what they called Rock Hill because "he was there," he being their regimental commander Colonel Orin D. "Hard Rock" Haugen who was right up front with them. After fighting by their side through several engagements, Colonel Haugen had gained a reputation as a serious fighter.

All of his paratroopers had, actually. Sixth Army's Lieutenant General Walter C. Krueger called Hard Rock's unit, "the God-damned fightingest outfit I have ever seen!"

But by December 21, 1944, that "fightingest outfit" was still miles away from the beaches of Ormoc Bay with a stubborn line of enemy defenses standing in their way. COL Haugen, fresh from a late meeting with MG Swing, decided an early attack would be the most effective means of eliminating Hacksaw Ridge’s last defenders, and for good reason. As D Company's 1LT Carrico explained, "The Japanese were famous for sleeping late."

Hard Rock also told his men to shave and clean up since MG Swing would soon come through with the 187th Glider Infantry Regiment, which led D Company's S/Sgt. Wilbur Wilcox, Wilbur to declare, "Scraping a month’s growth of beard off was agony!"

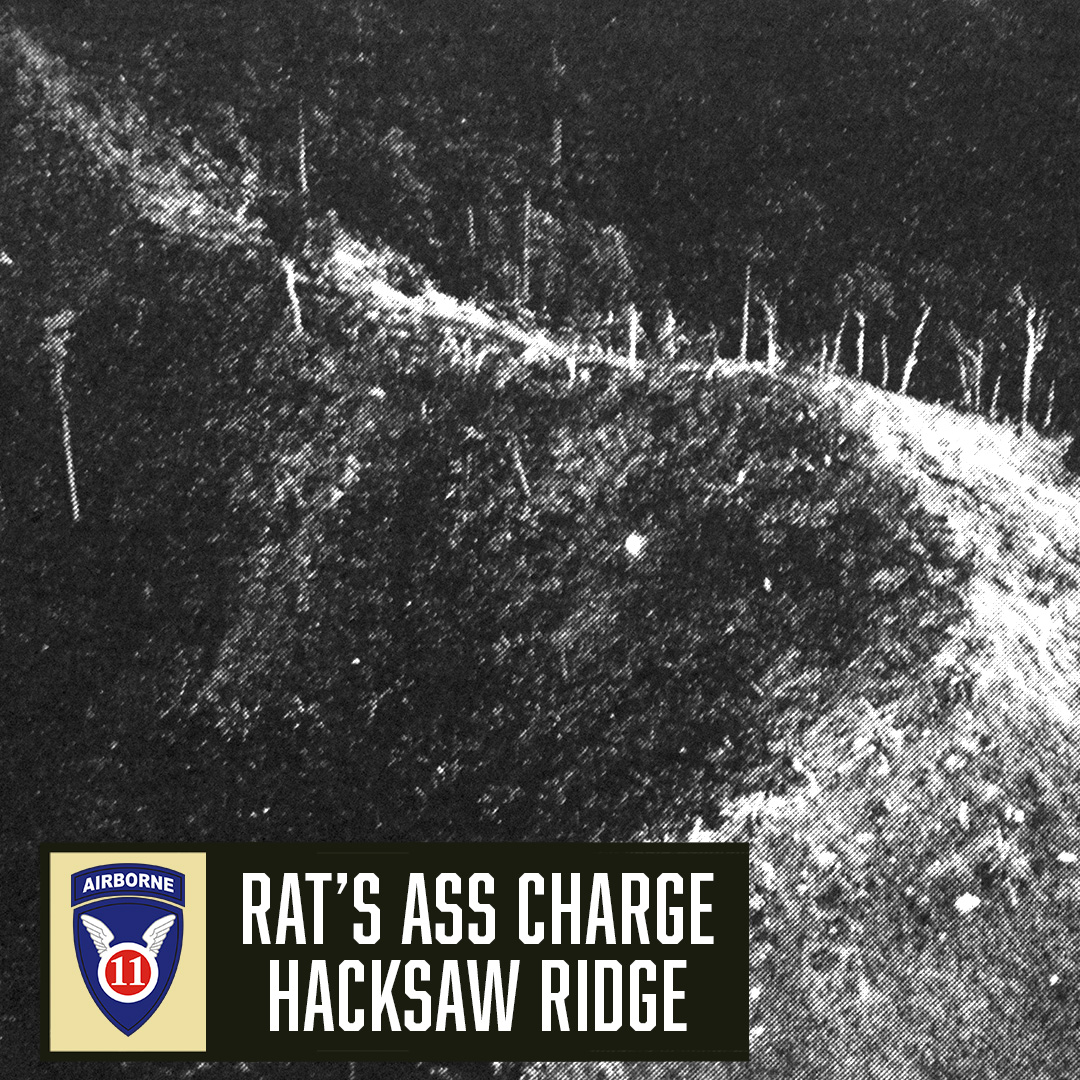

At 1900, CPT Stephen "Rusty" Cavanaugh was notified that D Company would affect the frontal attack the following morning, December 22 (D+35). Rusty was also informed that the trail leading up to the enemy positions (pictured to the right) was narrow and densely forested and with night’s darkness now upon them, no reconnaissance could be made. With far too little information for his taste, CPT Cavanaugh left Battalion HQ.

At 1900, CPT Stephen "Rusty" Cavanaugh was notified that D Company would affect the frontal attack the following morning, December 22 (D+35). Rusty was also informed that the trail leading up to the enemy positions (pictured to the right) was narrow and densely forested and with night’s darkness now upon them, no reconnaissance could be made. With far too little information for his taste, CPT Cavanaugh left Battalion HQ.

"We are going to hit them just before daylight and take the ridge," he told his assembled platoon leaders. Gambling on stealth and surprise, Dog Company would pass through Fox Company’s positions and cross the Line of Departure in a column of platoons. 1st Platoon would take the lead and affect the main assault and Rusty elected to march directly behind 1st Squad which would allow better operational control.

After being told of their mission, "We were issued three K-Rations…and I ate all three that night," said PFC Charlie Jones. "E and F Companies had the hell knocked out of them; I thought 'Why save them?'"

E and F Companies had indeed "had the hell knocked out of them" earlier that day. Hoping to get to Ormoc before GEN Swing sent the relatively-fresh 187th GIR (which was on its way) to break through to the coast, COL Haugen had sent E and F Companies up the steep southern flanks of what 2nd Battalion had called "Hacksaw Ridge" after COL Hacksaw. The young paratroopers of E and F Companies could smell the sea breeze in the air, but quickly found themselves facing a well-entrenched foe in their way.

While they inflicted heavy losses on the enemy, and advanced 900 yards southwest, 1LT Andrew Carrico noted, "After repeated unsuccessful attacks against a tenaciously defended enemy strongpoint, (E and F Companies were) forced to disengage and establish a perimeter for the night."

A few hours after D Company finished their late night preparations for their own push up Hacksaw Ridge, as a morning rain fell, scout PFC David Vaughn of led 1st Platoon across the LOD at 0400 while the rest of D Company hung back. The spine of the ridge that 1st Platoon was cautiously moving up was just too narrow; in fact, CPT Cavanaugh later explained, it was so narrow that "In actuality the company was attacking with a two or three man front."

A few hours after D Company finished their late night preparations for their own push up Hacksaw Ridge, as a morning rain fell, scout PFC David Vaughn of led 1st Platoon across the LOD at 0400 while the rest of D Company hung back. The spine of the ridge that 1st Platoon was cautiously moving up was just too narrow; in fact, CPT Cavanaugh later explained, it was so narrow that "In actuality the company was attacking with a two or three man front."

Moving up in such a narrow column, the Angels quietly scaled the trail to a slightly wider area roughly two hundred yards from the enemy’s suspected positions. Pausing to quietly fix bayonets and recheck their rifles, machine guns and ammo, under orders for silence the Angels shared nods of good luck before 1st Squad wheeled left off the trail while 2nd Squad headed to the right.

1st Platoon was divided thus:

Platoon HQ (pictured in photo to the right) included Platoon Leader 1LT Andrew Carrico, T/SGT William Corley, S/SGT George J. Cushwa, CPL Eldon Norton and PFCs Marion Crowl, Joseph Signor and Alfred "Al" Haar.

1st Squad’s thirteen members consisted of S/SGT George Taylor with SGT Archer Copley as assistant, ammo carrier PFC George Schlobohm, and riflemen PFCs Sam Sheffield, Arthur Chlebove, Elmer Eutsler, Charlie Jones and John Tkaczyk with T-5 George Locke and PVTs Cass Wotusiak, W. E. Milbrant and George Hammond.

2nd Squad’s roster consisted of fifteen soldiers PFCs William L. "Bill" Dubes, John H. Bittorie, Russell C. Kilcollins, Thomas W. Talbot, Earl D. Richardson, James W. Tuten, Charles N. Wise, Augustus F. Wilder, Harvalee L. Watson, Henry A. Olbrych, David V. Vaughn and PVTs Stewart D. Stevenson, Gilberto C. “Slick” Sepulveda, Myron W. Pickens and William R. Pugh.

As dawn tried (but failed) to creep through the heavy clouds, 1st Platoon's advancing 2nd Squad noticed a Japanese sentry at the edge of the field fifteen yards away to the right. The young paratroopers watched as scout PVT Sepulveda of El Paso, TX snuck forward, bayonet at the ready, but when the enemy slowly turned and noticed Gilberto, “Slick” shot him which drew the attention of the sentry’s comrades lounging close by. Slick fell with their opening volley.

CPL Wilbur Wilcox noted, "In the dim light, the Japanese were caught sleeping and were slaughtered. As the morning got lighter, we sped up the attack. (Later) as the trail spread out into the bivouac area, the entire Company became involved. The Japanese were not expecting an early morning attack and were surprised."

Hearing those initial shots off to his right, 1LT Andrew Carrico bellowed D Company’s catchphrase, “Rat’s ass!”, which signaled 1st Squad to throw grenades and hit the dirt (PFC David Vaughn had declared once back during stateside training, “I don’t give a rat’s ass!” and the phrase stuck). Explosions soon shattered the morning air as 1st Squad engaged the startled Japanese on the left with CPT Stephen Cavanaugh staying just behind my grandfather, 1LT Carrico.

Hearing those initial shots off to his right, 1LT Andrew Carrico bellowed D Company’s catchphrase, “Rat’s ass!”, which signaled 1st Squad to throw grenades and hit the dirt (PFC David Vaughn had declared once back during stateside training, “I don’t give a rat’s ass!” and the phrase stuck). Explosions soon shattered the morning air as 1st Squad engaged the startled Japanese on the left with CPT Stephen Cavanaugh staying just behind my grandfather, 1LT Carrico.

2nd Squad, now fully engaged with the Japanese after PVT Sepulveda's action, hurled their own grenades then began to rush towards the enemy's first line of defenses. PFC John Bittorie of Brooklyn, NY hurled phosphorous grenades on the run to burn enemy positions on the right of the platoon line and in all the excitement, the 6’ 2” machine gunner ran into a tree branch which smashed his nose and sent his helmet tumbling (John had already lost his front teeth in a North Carolina bar fight). Eyes blurry from the pain, Bittorie failed to notice the Japanese soldier six feet away drawing a bead on his head. Luckily PVT Augustus Wilder did and promptly dropped the enemy.

With the entire platoon now committed, PFC Bittorie’s ammo carrier PFC Russell Kilcollins and Assistant Gunner PVT Stewart Stevenson ran to the dazed machine gunner, still on his back, who muttered to himself, “Sunnuvabitch, right between the eyes.” Realizing that the Brooklynite believed he had been hit by enemy fire, Kilcollins pointed to Bittorie’s "enemy" and yelled, "You’re the dumb sunnuvabitch! Get up, you ran into that tree limb!"

Pressing up the hillside, the firefight grew in intensity and as 1st Platoon's push momentarily stalled due to enemy sniper and machine gun fire, 1LT Carrico and CPT Cavanaugh realized that besides the expected Main Line of Resistance (MLR) 1st Platoon’s thirty-five Angels had stumbled onto a Japanese column of around 150 Japanese on a trail 10-15 feet wide.

"It was a machine gunner’s dream," Grandpa/1LT Carrico recalled.

Full of adrenaline from his "encounter" with the tree branch, off to the platoon's right PFC John Bittorie shook off the stinging pain from his damaged nose and asked for a full belt for his .30 machine gun which PVT Stevenson helped load as bullets zipped overhead. Fully expecting that their gun would be needed, Kilcollins and Bittorie had spent the previous evening cutting belts into smaller, easier-to-carry lengths.

John then slung his 30-pound 1919A4 Browning light machine gun on webbing over his shoulder. Grabbing the barrel with an asbestos mitt, Bittorie rose to his feet, then bellowed challenges to the Japanese defenders, shouting: “Banzai, rat’s ass! Who’s with me?!”

1st Platoon watched the exposed “Bad Soldier” roar at the top of his lungs and fire a burst from the hip at 400-550 rounds per minute before John charged towards the enemy lines. With decaying jump boots and rotting uniform exposing bleeding jungle ulcers on his legs and body, Bittorie’s charge galvanized 1st Platoon into performing a Banzai charge of their own.

"Bittorie was a soldier that was a great soldier in combat, but he wasn’t worth a damn in the every day,” Grandpa/1LT Carrico chuckled. “He was always in trouble, stuff like that."

"He was an excellent soldier," remembered PFC Billy Pettit. "But he was a brawler. He was always fighting someone."

"John Bittorie was kind of a black sheep," noted PVT Charles L. Jones. "And quite mean."

"He really showed his mettle (on Hacksaw Ridge)," Grandpa added. "He came through."

Inspired by Bittorie’s charge, 1st Squad on the left led by 1LT Carrico and SGT George Taylor and 2nd Squad on the right led by Grandpa’s friend S/SGT George “Reb” Cushwa and PFC William Dubes began a trotting marching fire line up the hill that decimated the discovered Japanese column and defensive positions on the ridge. Cushwa had helped evacuate the wounded to the rear then hurried back to lead 2nd Squad and for his daring leadership, Grandpa recommended the Staff Sergeant from Roxboro, NC for the Bronze Star, saying, “he was a helluva nice guy.”

Inspired by Bittorie’s charge, 1st Squad on the left led by 1LT Carrico and SGT George Taylor and 2nd Squad on the right led by Grandpa’s friend S/SGT George “Reb” Cushwa and PFC William Dubes began a trotting marching fire line up the hill that decimated the discovered Japanese column and defensive positions on the ridge. Cushwa had helped evacuate the wounded to the rear then hurried back to lead 2nd Squad and for his daring leadership, Grandpa recommended the Staff Sergeant from Roxboro, NC for the Bronze Star, saying, “he was a helluva nice guy.”

Many in 1st Platoon felt that John Bittorie deserved the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. The "screw-up" from Brooklyn, who would retire a Command Master Sergeant with over 30 years of jump status, said decades later, "There are two kinds of military reputations. One is official and on paper in Washington, DC. The other is the one that goes from bar to bar from the mouths of those who served with you there. That is the only reputation I ever really cared about."

After the Rat's Ass Charge, John's reputation flew from the mouths of those he served with there, though he modestly said that their success was only due to the leadership of CPT Cavanaugh and my grandfather 1LT Carrico. Bittorie explained that "to get so close to the Japanese position undetected and the fast reaction of the assault while catching the Japanese withdrawing was the key to success."

Inspired by John’s charge, the Angels rushed forward with shouts of “Rat’s Ass!”, “Banzai!”, “Habba, habba!” and their old chant of “48, 49, 50!”. PFC Charlie Jones of 1st Squad remembered watching panicked Japanese soldiers diving off the ridge, saying it was like shooting rabbits in heavy brush.

CPT Cavanaugh noted, "This forward surge by the company continued for two to three hours with the enemy running in desperation, but losing the race."

Lest we picture a group of fresh, healthy paratroopers making the assault, the truth is that most of 1st Platoon was sick with one debilitating jungle malady or another (or several) and all were suffering from malnourishment. SGT Royalle Streck, for example, was so feverish that he had to be guided down the hill after the fight as he could not even walk straight.

No, 1st Platoon’s assault was affected by a small band of brothers who refused to quit or let each other down. As Marine aviator, astronaut and U.S. Senator John Glenn explained, "You train people to have more loyalty to their unit than they have to themselves, to the point where people will go out and do things that defy all instincts of self-preservation."

Like make a Rat’s Ass Charge against ten-to-one odds.

"I think the frustration and pent up anger of many days of hardships and siege (in the mountains) set off this charge on the enemy position. (We) shot everything in sight," PFC Bill Dubes added.

A note in the regimental journal simply says, "1st Platoon of D Co pulled a ‘rats ass’ charge on the Japanaese at dawn… The Japanese haven’t stopped running."

"Jungle foliage was thick, making it difficult to get through," Grandpa/1LT Carrico noted of their push up and across the ridge. "We somehow kept together, fighting until about noon when Captain Cavanaugh passed another platoon through us and we were able to stop for a much-needed rest."

With rain now falling, 1st Platoon moved into the retreating enemy’s former positions. Enemy dead lay everywhere, and some were still twitching as the paratroopers kicked dirt over the corpses at the bottom of the ten to twelve foot deep troughs. The Angels breathed sighs of relief that they had survived another engagement as the success of their initial assault settled in.

"I estimated we killed over 300 that day," Grandpa/1LT Carrico later recalled.

CPL Murray Marshall Hale added, "The enemy never had a chance! How proud I am of D Company."

Listening to reports of the 1st Platoon’s effective rout on the ridge, COL Hard Rock Haugen turned to his staff and said, "Tell (General) Swing we will have the trail (to Ormoc Bay) open for him today."

"With more bravado than sense," CPT Cavanaugh recalled, "I sent a runner to the rear to inform the Battalion Commander (Major Holcombe) that we had overcome the enemy with a bayonet charge and that he was on the run and that we were in hot pursuit." Rusty wanted to press the attack with the rest of D Company, which had now assembled, but his runner surprisingly returned with orders to halt.

"With more bravado than sense," CPT Cavanaugh recalled, "I sent a runner to the rear to inform the Battalion Commander (Major Holcombe) that we had overcome the enemy with a bayonet charge and that he was on the run and that we were in hot pursuit." Rusty wanted to press the attack with the rest of D Company, which had now assembled, but his runner surprisingly returned with orders to halt.

"Needless to say," Rusty said dryly, "I disregarded the order, feeling that if we paused the enemy would have a chance to regroup and establish defensive positions."

D Company pushed forward a short distance when another runner arrived and emphatically repeated Holcombe’s order to stop. Four hours and 2,500 yards after the attack began, Rusty reluctantly had his sweat-drenched company move off the trail to rest in a grove of palm, mango and papaya trees overlooking Ormoc Bay where they could see friendly 7th Infantry positions at the base of the mountains.

To their surprise, the next day, December 23 (D+36), a much fresher-looking 2nd Battalion of the 187th GIR, led by General Joseph Swing himself, passed D Company’s perimeter to contact the 7th ID near Albuera (and receive the accolades as the first of the 11th Airborne to reach Ormoc).

General "Jumping Joe" only paused long enough to tell CPT Cavanaugh, "Nice job," before moving on.

"My thoughts regarding that gentleman were at that (moment) anything but complimentary," Rusty recalled. With steel in their eyes, D Company watched the clean-uniformed and apparently much better fed glider-riders march past their grove towards the beach. With most of the fighting finished, the exhausted paratroopers believed the march to Ormoc Bay should have belonged to the 511th PIR.

It was rumored that COL Haugen’s men had been halted, in part, because of their haggard appearance. While they had inflicted destruction upon the enemy, the Brass felt that after their month-long ordeal in Leyte's mountains, the paratroopers looked like death themselves and wanted a fresher, clean-looking unit to arrive on the beaches for publicity photos and film reels.

This treatment was a source of resentment for the 511th PIR for years to come since General Swing later boasted that on December 22 alone "his Angels" killed 750 enemy and captured 2 mountain howitzers and 16 light and 7 heavy machine guns. Jane Carrico, 1LT Carrico’s second wife, said "the old troopers" mentioned this incident with great bitterness at every regimental and division reunion after the war.

"D Company never received the acknowledgement deserved for affecting the breakout from the mountains of Leyte," CPT Cavanaugh objected, "except for our Regimental Commander who recognized what we had done." COL Haugen let D Company know he was "damn proud" of them.

As Rusty’s exhausted and worn (but still victorious) men sat overlooking Ormoc Bay, over six-thousand miles away CPT Dick Winter’s Easy Company, 506th PIR huddled in their foxholes in Bastogne’s frozen soil.

Feeling slighted by division brass, D Company and the rest of the 511th PIR’s 2nd Battalion dug in for the night, grateful that they were within a grove of fruit trees which provided a dinner of papayas and mangos. While the stench of enemy dead made slumber difficult, CPT Cavanaugh and his men rested easier, knowing that after a month of heavy fighting they could see (and thankfully smell) the ocean just a few miles away. Let Gen. Swing and his darlings in the 187th GIR "clear" (i.e. walk safely through) the last stretch; D Company knew that "Ali Haugen’s Thieves" had paved the way with their blood, sweat, toil and tears.

Grandpa/1LT Carrico worked hard to submit the names of the charge's fighters and leaders for commendations. CPT Cavanaugh, however, wanted to make sure that Carrico wasn't overlooked. Rusty had watched Andy courageously lead 1st Platoon for over four hours in the heat of battle and wrote:

"During a four-and-a-half-hour attack against stubbornly defended enemy positions, First Lieutenant Carrico, repeatedly exposing himself to hostile fire, remained forward with the lead scouts and directed his platoon’s attack against the enemy strong points. His courageous actions inspired the men to heroic efforts, enabling them to pierce the strong defensive positions and drive the enemy from the area. The outstanding leadership displayed by First Lieutenant Carrico reflects great credit on himself and his military service."

His leadership at the front would earn 1LT Carrico his first Bronze Star.

"In my opinion it should have been a Silver Star," he observed without the least hint of guile. CPT Stephen Cavanaugh pulled my grandmother Jane aside years later at a division reunion and confirmed Andy’s assessment. The former captain actually put Grandpa in for the Silver Star and Rusty (then a retired colonel and former Chief SOG) expressed disappointment that Andy had not received the proper recognition for what he did on that ridge so many years ago.

It was a sentiment that nearly every 11th Airborne Division member I have ever spoken with expressed; not that D Company hasn't been recognized, but rather that their entire division has failed to obtain recognition similar to that gained by the 101st and 82nd Airborne Division's during the war.

To paraphrase several troopers, "They were 'over there' in Europe, we were 'over there' in the Pacific. They get books, movies and mini-series, we get forgotten and overlooked."

On Christmas Day, the battered and bloodied paratroopers of D Company, along with 2nd Battalion, began their slow march down the now-open trail to friendly lines on Ormoc Bay. Carrying their wounded with them, the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment sang as they moved through the jungle, a touching story that I tell more fully in another article titled, "When the Angels Sang on Leyte, Christmas of 1944". I highly encourage you to read this special holiday account that brings the Christmas spirit no matter what time of the year you read it.

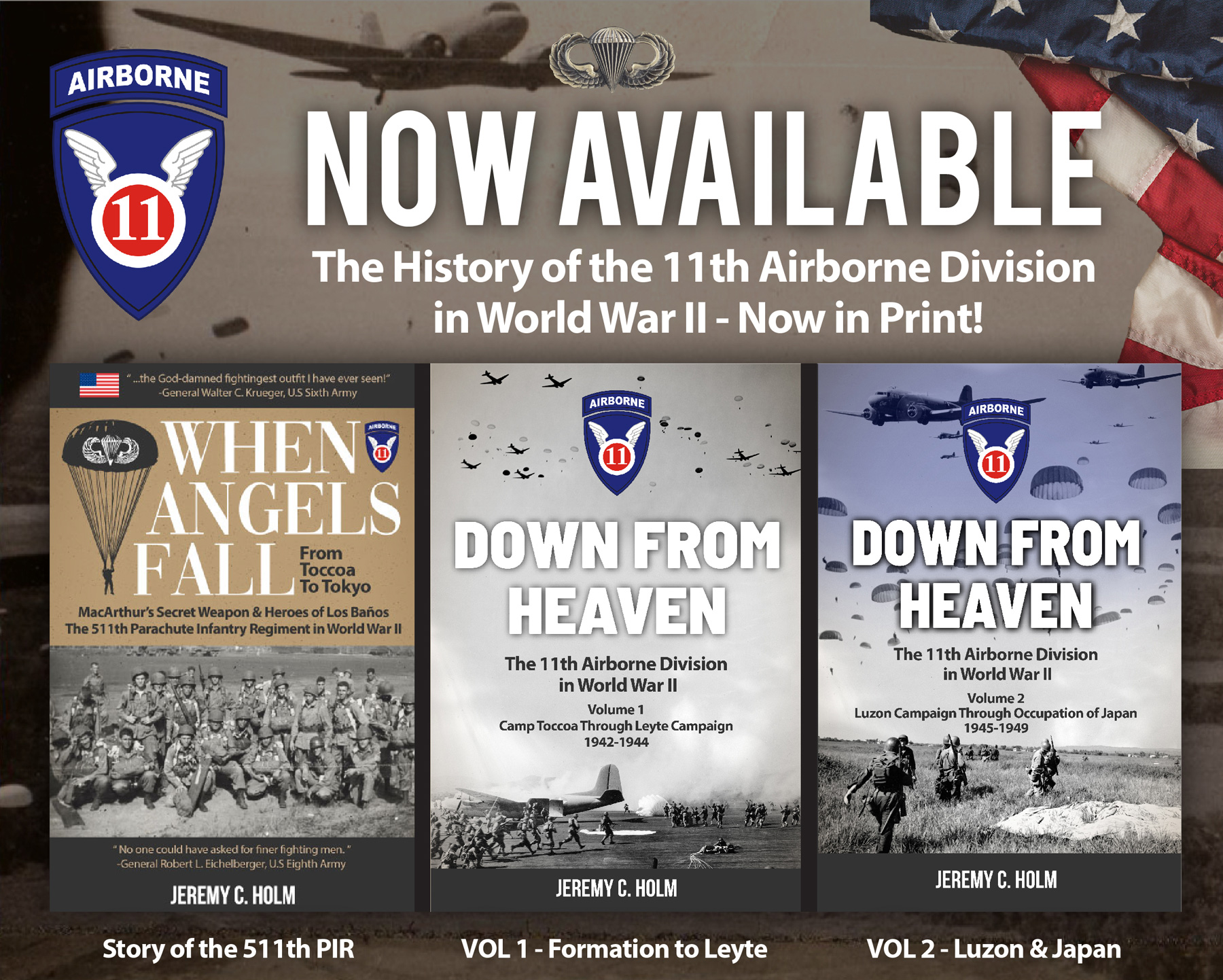

Thank you for taking the time to read this account of the Rat's Ass Charge. If you would like to learn more about the 11th Airborne Division in World War II, please consider purchasing a copy of our books on the Angels: